How can ancestral artistic traditions be sustained and revitalized? How can dominant narratives circulating around Native American culture and the art historical canon be decolonized? Arkansas-based artist Jay Benham works at the nexus of these questions, expanding the visual language of Kiowa Ledger Art to share ancestral stories. Through a collaborative process, Benham engages the vitality, oral tradition, and creativity of his Indigenous community.

The following conversation was edited for length and clarity.

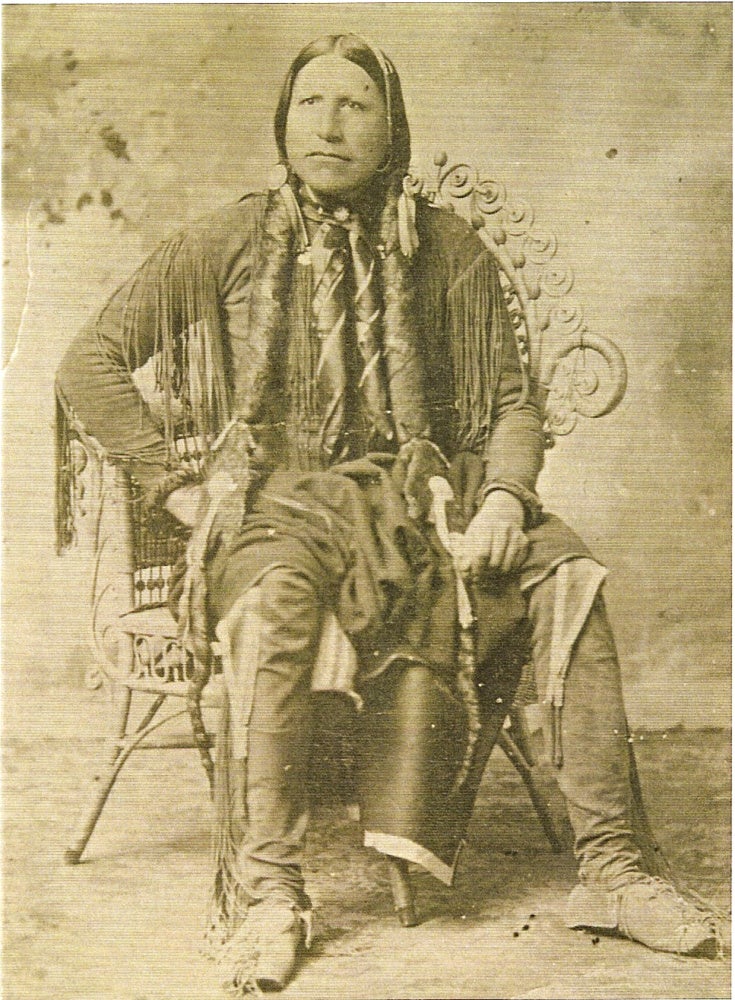

Tara Escolin: You’ve shared stories about your grandfather, Tonemah (Quote-Ko-Keah), and the line of Kiowa chiefs you descend from, such as Red Otter, who went to war against the U.S. government. You’ve spoken about how your grandfather’s generation was suspended between ancestral traditions, and the physical and spiritual colonization that ensued. Why is your work centered on this particular historical moment?

Jay Benham: Cladio Saunt calls it a “colonialism of consciousness” in his book Unworthy Republic.1 That’s a fascinating era when you have to either change, survive, or perish. It shows the strength and resiliency of Native American people, who’ve gone through dramatic and desperate change. Native people like my grandfather had to learn a whole new way of laws, thinking, and monetary systems—how to negotiate, how to protect their family, how to make a living while still preserving traditions. The government was totally against their religion. For instance, our Sun Dance—called the Medicine Lodge—was outlawed, and the buffalo were exterminated. You have to have a buffalo to have that ceremony; so many things were pitted against that era, in the late 1800s. It’s really a testament to their tenacity to be able to survive, much less excel, in many areas.

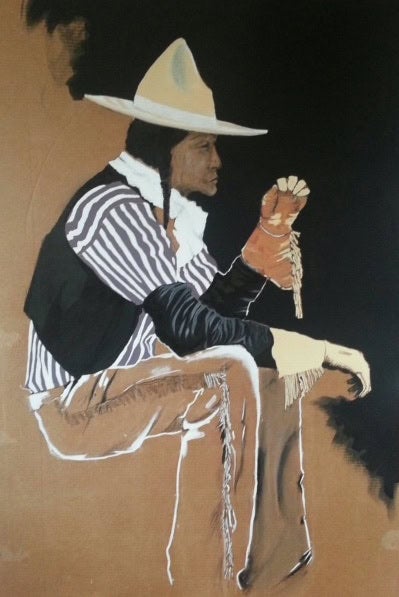

TE: Some of your paintings and performative work, such as Refrigerator Repair School Drop-Outs (2004), is based on childhood visits to Oklahoma where you spent summers with your Kiowa family. These stories also depict figures at the confluence of two cultures, as in the works Reservation Débutante (2022) and Going to a Sing (2022). I’m wondering about the connection between these figures and the tenacity you describe in the stories about your grandfather’s generation.

JB: There was still discrimination against that next generation from the dominant culture. With Reservation Débutante, she’s not only preparing in the presence of her aunts and mother, who are judging her from their standard. She’s also facing going to the parade, to be on display for the whole town, whether they’re Anglo or other tribes. She still has to contend with that interpretation of who she is.

How does she cope with that? How do these young men in Refrigerator Repair School Dropouts cope with their future? They know their future is not in the pool hall. So how do they survive? Do they go ahead and accept an offer to go to a boarding school? There are still choices to be made on survival. I see that same dilemma affecting us all, but even more so when you’re from a culture that has a different view of life, stories, and traditions than the dominant culture.

TE: How do you view your work in relation to the tradition of Ledger painting, and what inspired you to expand your practice of painting into the realms of tableaux vivants and performance?

JB: I think about my grandfather and his generation, who did so much with so little. How can I take my art to another level, like he took his existence to another level? Why not take Ledger Art and similarly expand it? Candace Green, in her book on the artist Silver Horn titled Silver Horn: Master Illustrator of the Kiowas, said you can place Ledger Art into three major classifications: the narrative/storytelling, the spiritual, and record keeping.2 What we’re doing in the performances is exactly that. The narrative and spirituality comes from the story of the Kiowa God, Dwk’i [and the sacred use of images in that story].

Spiritually, the Kiowas have always had, we say, a cherished responsibility to do art. The record-keeping is of what my generation experienced in Carnegie, Oklahoma: going to the pool hall, or for the young woman, getting ready for the parade at the Indian Fair, or just experiences of a family making transitions.

TE: The process for creating performances based on your paintings is collaborative and involves your daughter, Brooke Benham, who works with a team to reproduce a painterly texture in three dimensions by applying makeup onto the actors’ clothing. Can you tell me more about this collaborative process that essentially animates your paintings?

JB: It’s extensive. None of our installations could even get off the ground without a collaborative effort from Brooke, our producer Rumwolf, and others, to implement the design and keep the ethos of the work. It takes a lot of meetings and a lot of rewrites, which Brooke implements. It takes Brooke out in the field, looking for clothing and furniture. The effect is very interesting when the actors are really still, then start moving; the audience is like “Wow!”

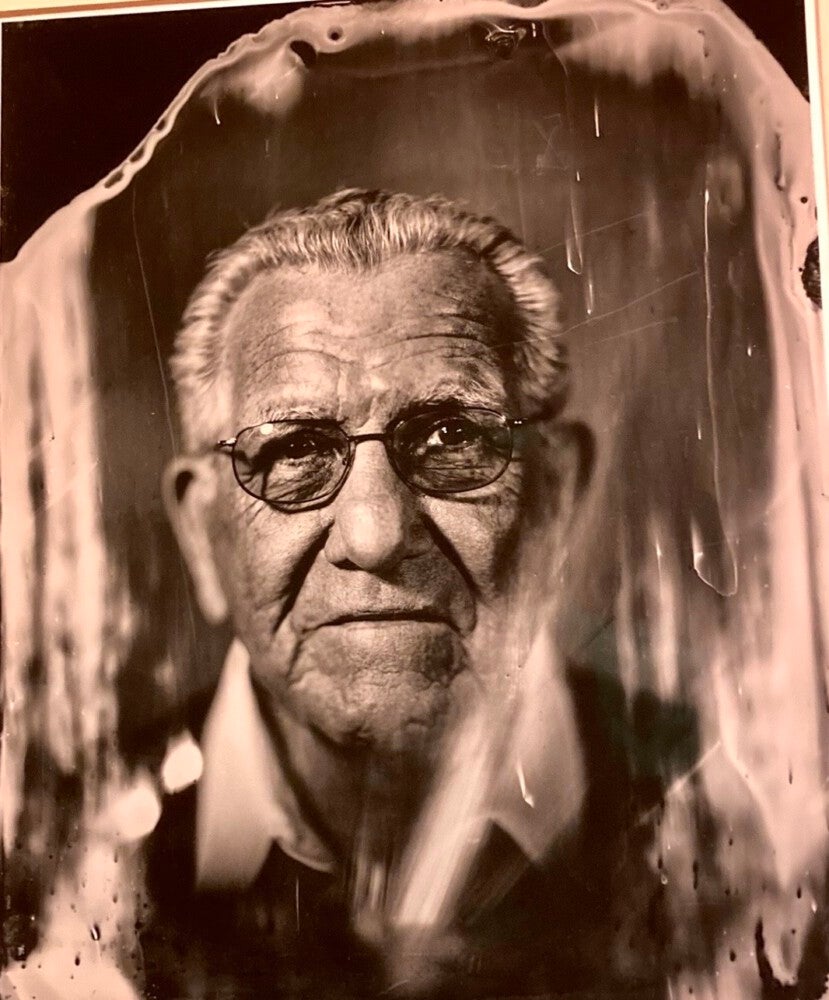

TE: Your next project involves recording family members’ experiences with the boarding school system, where the guiding ideology was to “kill the Indian…and save the man.” Can you share more about what you’re working on?

JB: The original policy was that it was more expensive to go to war and exterminate the Native Americans—it was cheaper to educate the “Indianness” out of them. All that originated through Captain Pratt, through the incarceration of these Southern Plains tribes at Fort Marion, where my great-grandfather, Lone Wolf, was one of the first. He went there, and Captain Pratt taught classes in math and other subjects. When they were released after a few years, some of them remained in the East, some came back home, and some went to schools like Hamilton and Carlisle.

That’s where the boarding schools started. The idea there was to eliminate all Native culture. We’re interviewing my family members who went to boarding school in the 1950s and 60s. We’re finding some positive stories where that policy seems to have backfired for the government, as these Native students excelled in whatever area they went into. We want to make an installation with their testimonials.

[1] Saunt, Claudio. Unworthy Republic: The Dispossession of Native Americans and the Road to Indian Territory. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2021.

[2] Greene, Candace S., and Donald Tofpi. Silver Horn: Master Illustrator of the Kiowas. University of Oklahoma Press, 2002.