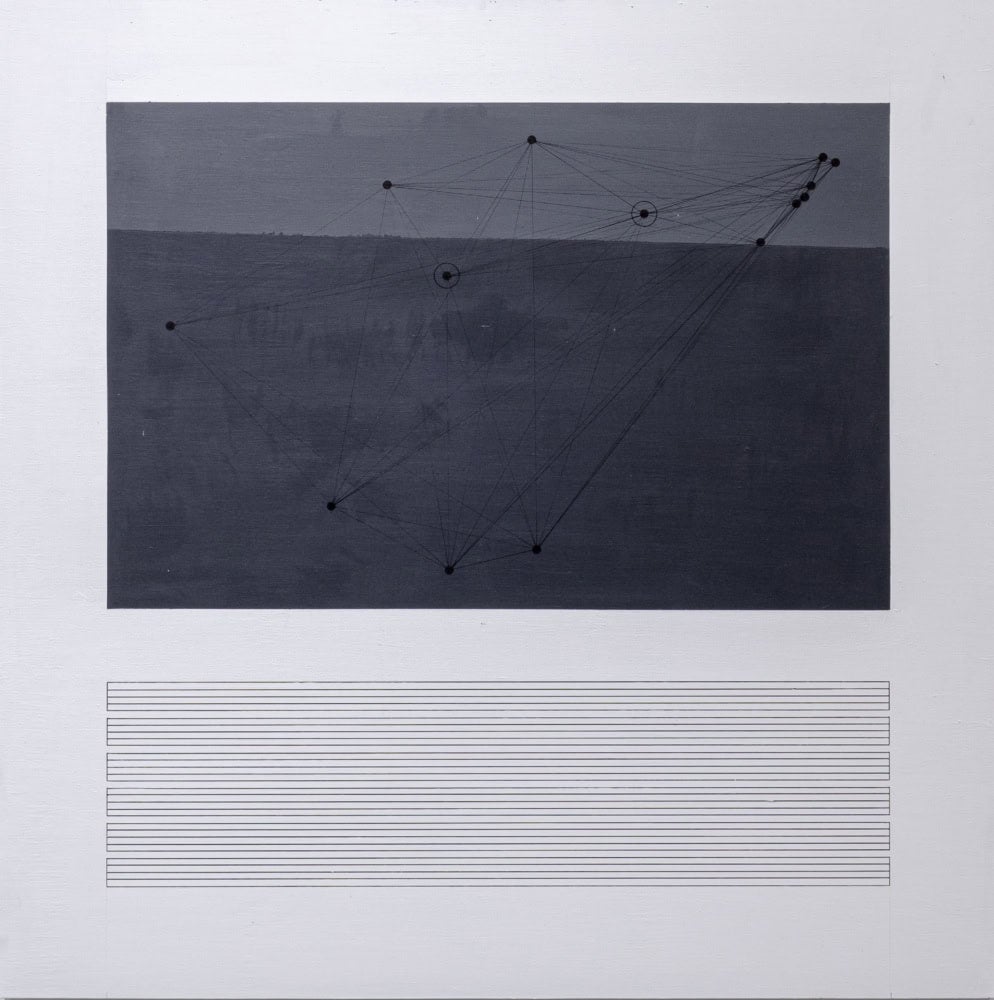

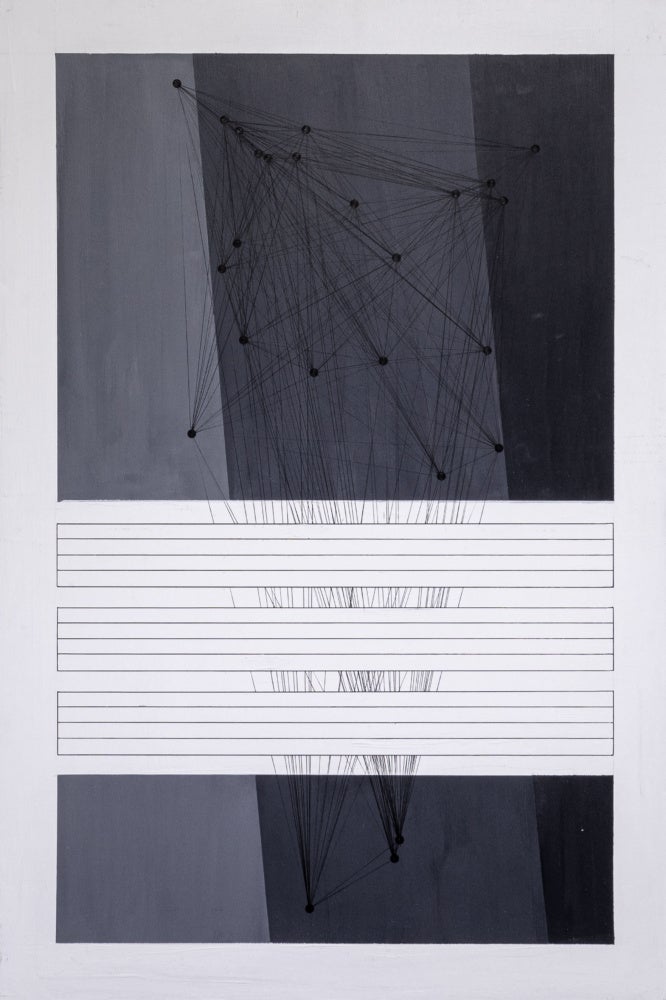

When I sat down to talk with Corey De’Juan Sherrard Jr., he had recently performed compositions from his work, Songbook for Black Constellations, 2022-2023, for the 2024 Texas Biennial. De’Juan Sherrard Jr., a Houston native, is a multidisciplinary artist and member of several creative communities, ranging from DJs to beatmakers, painters to rhymesayers. His visual work is heavily inspired by music and instruments that create or amplify sound. De’Juan Sherrard Jr. deploys microphones and microphone stands, cassette tapes, tuning pegs, and piano wire to make artwork that highlights the materiality of Black musical expression. His grayscale Constellation (2022-2023) paintings utilize the lines of a musical staff without the notes on the graph. Instead, the plotted points and the lines that connect them exist in a field of swirling grays and multiple horizon lines that evoke the feeling of (outer) space. The notes are demographic data from American cities: largest Black populations, cities with Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and those that once had Negro League baseball teams. When performed, saxophone and drums transform the compositions into cacophonic envelopes carrying chaos and hope, swing and syncopation. In our conversation, we discussed internet nostalgia, Black abstraction, and collective world-building.

This interview had been edited for length and clarity.

Jeremy Johnson: It seems like you’ve always been drawing, probably since you were a kid, but also making music or learning music your whole life. Do you remember those starting at different times, something you started first?

Corey De’Juan Sherrard Jr.: Funny enough, I feel like kids, they start drawing and then they stop, but I was one of those kids that liked drawing, and I thought all kids drew the way that I did. I just kept drawing. I was drawing and writing all the time. I didn’t know other kids weren’t writing. I was super interested in buying composition books. Music happened because of my granddad. He got me a trumpet and I played trumpet for three years. Then I got really into hip-hop. I started to identify myself with music more in middle school, too. I quit band, but I was still really into digging for music like the Limewire days.

JJ: I remember those days. Just digging, searching, just finding things. There was so much on Limewire too.

CDSJ: I was really surprised with the stuff I found on there. and some of the viruses.. It was kind of worth the risk. My brother and I got in trouble, downloading a bunch of stuff and then the computer would be out for like a month, and then it would come back up and we’d be like, “Oh it’s time!”

JJ: We’re talking about this past or bygone era of internet usage. Are there things that you’re nostalgic for?

CDSJ: I’m nostalgic for mixtape days and how excited I was when I would get home from school and DatPiff would have the hottest mixtapes, the most downloaded mixtapes. I was just going through there and downloading as much as I could. I think now, music is still as accessible. You just have to do it in different ways. I feel like Bandcamp is one of those places where you can find really good music. Archive.org is one of those places where you can find very interesting soundbits like interviews and live recordings of jazz musicians, along with books. Their Wayback Machine is great for that, too. To find all these websites from the early 2000s and articles and forums with people talking about, “Ya know, Little Brother just dropped this album and it’s crazy.” Each community has its own website too. Recently, I’ve been trying to get into new media, and there are conversations around art, tech, and design intersecting, and old websites that delve into those conversations.

I think that era plants the seeker in you. The fact that you have to go out and find the thing that’s not readily available to you. I’m very much about figuring out a way to find something that I want, even if I have to pay for it, and if I don’t, that’s great too!

JJ: One of the things it seems you do consistently is digging and researching, and paying attention to history. Can you talk to me about the relevance of history in your practice? Or your messaging, what are you trying to tell people when you’re digging and bringing it forward?

CDSJ: My primary objective whenever I’m making art and I’m making music is wanting to express how beautiful and fun it is to seek. I know this speck of the entirety of all knowledge in the universe. I don’t know anything really, and when you go about it that way, then you can see it two ways. You can either see it as, “OK, I’ll never know everything so why try?” or you can see it as “I’ll never know everything but that means that I’ll have an eternal or a lifelong journey of constantly seeking,” and there’s something very fulfilling about that. I feel like in America, we see things as if we’ve reached a destination, and it kind of ties into politics, too. We’re never gonna get to a destination where we’ve figured out all of life; we’ve figured out how to appease all people socially, culturally—everybody’s comfortable. It’s important for us to understand that in this moment, while there are things that are not right, there is a fight to be had for people who should have their wrongs righted. Accessibility, comfortability, love, peace…Having everything available to them to thrive. This is not to say that you should have an excess in riches, but access to your own abundance.

JJ: If every group could have what they need and didn’t try to keep other groups from having that same abundance… It seems like that could be attainable for us, but there are challenges.

CDSJ: Exactly. When I think about freedom, I’m thinking about living life with a certain type of agency. Agency looks different for a lot of people, and even though it may seem like there are people across the world that appear not to have freedom, they have cultural agency.

That’s why I make music. That’s why I want to do radio. That’s why I want to make art. That’s why I try to constantly feed this hunger to seek things and be not the idiot in the room, but to be the least knowledgeable at times.

JJ: Thinking about politics, and music, and visual art, it seems like you’ve been able to merge all of these things at this singular point. I’m thinking about your work Songbook for Black Constellations. You’re taking historical data, abstracting that into notes, and then you’re also playing those, and making music, making that bridge across abstraction, and bringing it back to the body, with music. Why is abstraction important for you?

CDSJ: Abstraction is important because it paints the idea of the future without actually giving you a dramatization. Similar to Islam, there’s no image of Allah. There’s a lack of understanding of how much power Allah has. With abstraction, you’re thinking about the essence of something more so than its image. I think it’s important to have the figurative when it comes to Black art, but it’s just as important to have the abstract in Black art as far as imagining the future. When I thought about integrating music into it, I was thinking about how important music is to Black life in America. I’m thinking about spirituals, the blues, jazz. It is like the true American art form, but a true, colonized American art form.

JJ: Black music.

CDSJ: Yeah, Black music. Yeah, there’s so much to explore with that. I’m really into systems, too, like Sol LeWitt. I’m into Charles Gaines. I’m interested in tapping into the essence the same way that Arthur Jafa does with his work. If I’m thinking of Black abstractionists further, I’m thinking of Julie Mehretu. I don’t know why I’m thinking of Noah Howard, who is a saxophonist.

JJ: But at the same time, yeah.

CDSJ: Yeah, jazz is abstract in a way, too. So yeah, Noah Howard, the saxophonist. Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, John Coltrane, and a whole bunch of other names, Arthur Blythe. The list goes on with inspiration for me as far as exploring the abstract, but I think that it is important to have that type of depiction of the future.

JJ: There’s a way that I see you, like many other visual artists and musicians, as a storyteller. But you aren’t telling a narrative driven by an individual protagonist. When I think of your work, I think of Blackness, in its abstraction, as sort of the protagonist in your stories. I’m seeing a lot of emphasis on the collective.

CDSJ: That’s exactly why, in the artwork, I use cities. The constellations are pretty much connections between cities, and that forms a network, which forms a figure in a way. So the conversations between the cities are really like, “Oh we’re all kind of experiencing a similar thing together.” There’s a unity in that. When I think about unity as far as Black life in America, a lot of unity comes out of culture, and music is a really big part of that too.

I choose to do systems with this thing, too, because it’s important for us to feel like we can engineer our own systems. We can engineer our own spaces. We can create a language of our own that can map out the future for ourselves, and it doesn’t have to look like it came out of any particular institution. It doesn’t have to look like a direct replica of whatever Frank Lloyd Wright would do, or Eames, or the people that invented the internet. I want us to feel like we can create our own. We can abandon the internet and create something different. We can build our own virtual spaces that aren’t so pervasive. We can literally do anything as long as we program ourselves to believe that we have the agency to build those things, and we feel like we can do it.

JJ: It’s through those connections with each other and knowledge sharing. Is that what you’re saying?

CDSJ: Exactly. It’s not about one person being the hero. Personally, I’m not really into the idea that all Black people want a hero or one person to tell them, “OK, I’m the one. We’ll do this, this and this.” It’s about us sitting with each other and saying, “OK, I really appreciate your contribution, and I want to extend whatever it is that you’re doing, so let’s work, let’s talk, let’s build.” On a cultural front, a scientific front, a social front. All of us, doing everything we need to do—a political front. Moving in all different directions, and as long as that propaganda and that information are out there, then people can come to their own conclusions about what they need for the future. That’s real freedom: really being able to come to your own conclusions about the future and what’s good for the future from an educated place. To have the agency to go out and seek that information, to be a real seeker for that type of freedom and understanding of freedom.