Chayse Sampy is rewriting history. Her multidimensional, mixed-media paintings are imbued with deep symbolism that addresses and challenges the centuries-long war on the Black imagination. We met in Sampy’s shared downtown Houston workspace to discuss the Black theorists who have guided her, living in the South, and her love for the color blue.

Amarie Gipson: I first encountered your work on Instagram, and the complexity of your figures struck me instantly. The multilayered faces have a cerebral and surrealist quality. You actually think about yourself in relation to the Afro-Surrealist tradition. How did you come to identify yourself in this way?

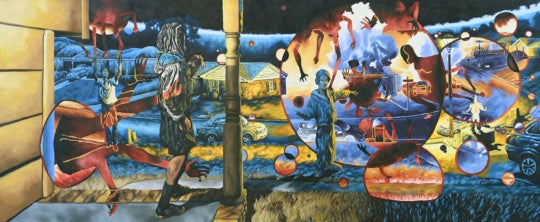

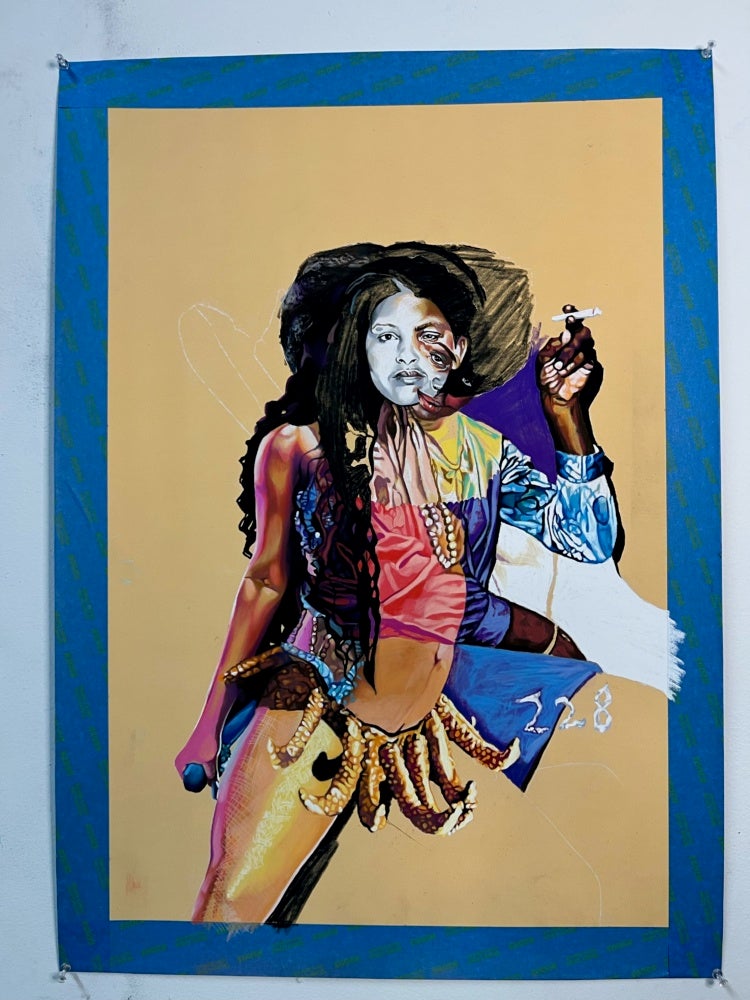

Chayse Sampy: Honestly, it was through watching movies and TV shows, like Get Out (2017), Us (2019), Swarm (2022), Atlanta (2016-2022), Lovecraft Country (2020), and Alice (2022), that I realized that was what I was doing in a 2D space. My work deals with the absurd reality of Black life, intertwining history with storytelling and myth-making. I create worlds that illuminate the miraculous nature of Black existence, the magic we possess. I portray posthumous bodies as creatures that prompt introspection on our humanity; they make us more aware of ourselves and of our place in the cosmos. That’s what I think Blackness does. My creatures symbolize a Black consciousness, a neural network that connects us across space and time. They represent complexity, possibility, and a multidimensional approach to identity.

AG: Your work is shaped by a rich tradition of Black theorists. Who are your intellectual comrades, and how have they helped you understand your relationship to self and, by extension, to the art you create?

CS: I say it was initially bell hooks. She had a way of seeing you, and she delivered criticism/insight with love. That’s really what I learned from her; the need for a holistic practice rooted in a love ethic. I’ve since delved into the works of W.E.B DuBois, Fred Moten, Toni Morrison, Tina Campt, Christina Sharpe, Deborah Roberts, and Dr. Joy James, among others. Currently, I’m engrossed in “Posthuman Blackness and the Black Female Imagination” by Kristen Lillvis.

AG: And what about visual artists? Who do you find yourself in chorus with?

CS: On the artistic front, my work is in dialogue with contemporary artists like Arthur Jafa, Nathaniel Mary Quinn, and Wangechi Mutu. Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016), is how I see my art functioning with its ability to capture the complex range of the Black experience. I relate to how Nathaniel Mary Quinn collages mediums in a somewhat violent/emotional manner to speak about a familial narrative. And I’m inspired by Wangechi Mutu’s world-building/bending, and the use of myth-making. There is a magic within her work that I hope to create.

AG: Yes! They each share an affinity for the grotesque that I see parallel in your work. And honestly, Jafa’s oeuvre has given us much to process. I appreciate how he foregrounds his Southern roots as the impetus for his urgent and critical examination of Black American life. How, if at all, does the South permeate your artistic approach?

CS: My art is a reflection of the places I’ve been, and I’ve only truly been in the South. Over the past few years, I’ve explored my ancestry which ties me quite heavily to Louisiana and Texas. I think both have interesting histories. Texas, on the one hand, was owned by the Spanish and had its own revolution to keep slavery intact; not to mention my maternal side migrated to Texas after the Civil War. I believe Louisiana has the most interesting and complex history in the nation. The unique interracial relations, the Code Noirs, the rebellions, my family’s history as sharecroppers, Katrina, and the eternal “party” that is New Orleans. I’m particularly drawn to New Orleans for its relationship to death, the fact that the dead are housed above ground and their mourning takes the form of celebration. Living in Louisiana for four years, the land felt haunted. It was in the way the trees hung over you, the memorialized plantations, it was in the rain. I’m not sure how to describe it.

AG: That’s really spot on because I’ve always imagined Houston and New Orleans as cousins, primarily because they’re both port cities. There’s something about proximity to water that creates this mystical sensibility. This makes me think about color and the prominence of blue in your palette. Are there particular histories connected to it that continue to resonate with you? Are there other colors that have a similar resonance?

CS: Blue is a significant through-line in my work. It symbolizes the sea, the luminal space where Blackness was birthed on the Middle Passage. I think of [blue] as the celestial waters, our mother’s waters; a faith-based relationship to water that could pull our ancestors overboard and walked them into the water. It’s evocative of the tumultuous weather Christina Sharpe writes about. In some instances, the blue is meant to represent coolness because if it’s one thing Black people know how to do is be cool (or maybe we are keeping our cool).

It reflects the [genre’s] ability to communicate multiple emotions at once, to overlap, to improvise, to be both strong and gentle. It is rooted in history yet still leaves room for individual expression. I see myself staying blue for a while, it’s reflective of where I am in my life. For me, it’s a place of simultaneous processing and creation. Eventually, I see myself moving into maroon. Maroon would be related to Maroon communities in America, thinking about what it means to live outside of slavery, to escape and create anew. Maybe this will come with more travel or a more forward-thinking mindset, either way, I look forward to it.