Reactivating obsolete technologies and derelict architecture, the artist Jackson Markovic captures and reimagines spaces where the unexpected arises in the thrum of dance, music, and desire. In a landscape of cultural ephemera, Markovic’s practice explores the pulse between public performance and private ritual while referencing club culture, social history, and the evolution of photography.

This interview was edited for length and clarity, and was originally published in print for the Atlanta Art Fair 2025 broadsheet publication, taking place from September 25 to 28, 2025.

Tara Escolin: Your past work documents Atlanta’s dance culture directly and indirectly, as well as some of the city’s marginalized areas. How do you interpret or reconstruct a sense of place within your artistic practice, and what draws you to these particular spaces?

JM: A lot of it is likely a skewed intuition shaped by very early photographs on the street, going places I probably shouldn’t have. I think through that I got over a certain internal discomfort and felt empowered to enter certain spaces. Now, I don’t know how that translates to new work; I’ve probably gotten more shy with a camera. It’s tempting to liken my sense of place as a reaction to living in Atlanta my entire life. However, there’s so many myths here, as with every city—I struggle to identify how I really feel.

TE: Your introduction to photography was in a traditional darkroom and you still shoot on film (using a 4×5 Monorail camera, which comes with many constraints). How does the materiality of analog processes inform your work?

JM: Despite the constraints of an analog medium, namely price and lack of outside resources, there is also a freedom or self-sufficiency. The lack of certain labs in Atlanta means I’ve figured out how to do many things myself. I am able to maintain a darkroom easier than a digital printer. There is also a less rote order to things: it’s more fluid to print in a darkroom than to send files back and forth.

I do tend to work better with the constraint. My early experiences with photography were in a black-and-white darkroom in high school. For each assignment we got one roll of 35mm film with thirty-six exposures, and used a simple Pentax K1000. That economy of image-making is so fundamental to how I experience images. Looking at the same thirty-six exposures for months imbued a consideration that has stubbornly remained even as my practice has grown.

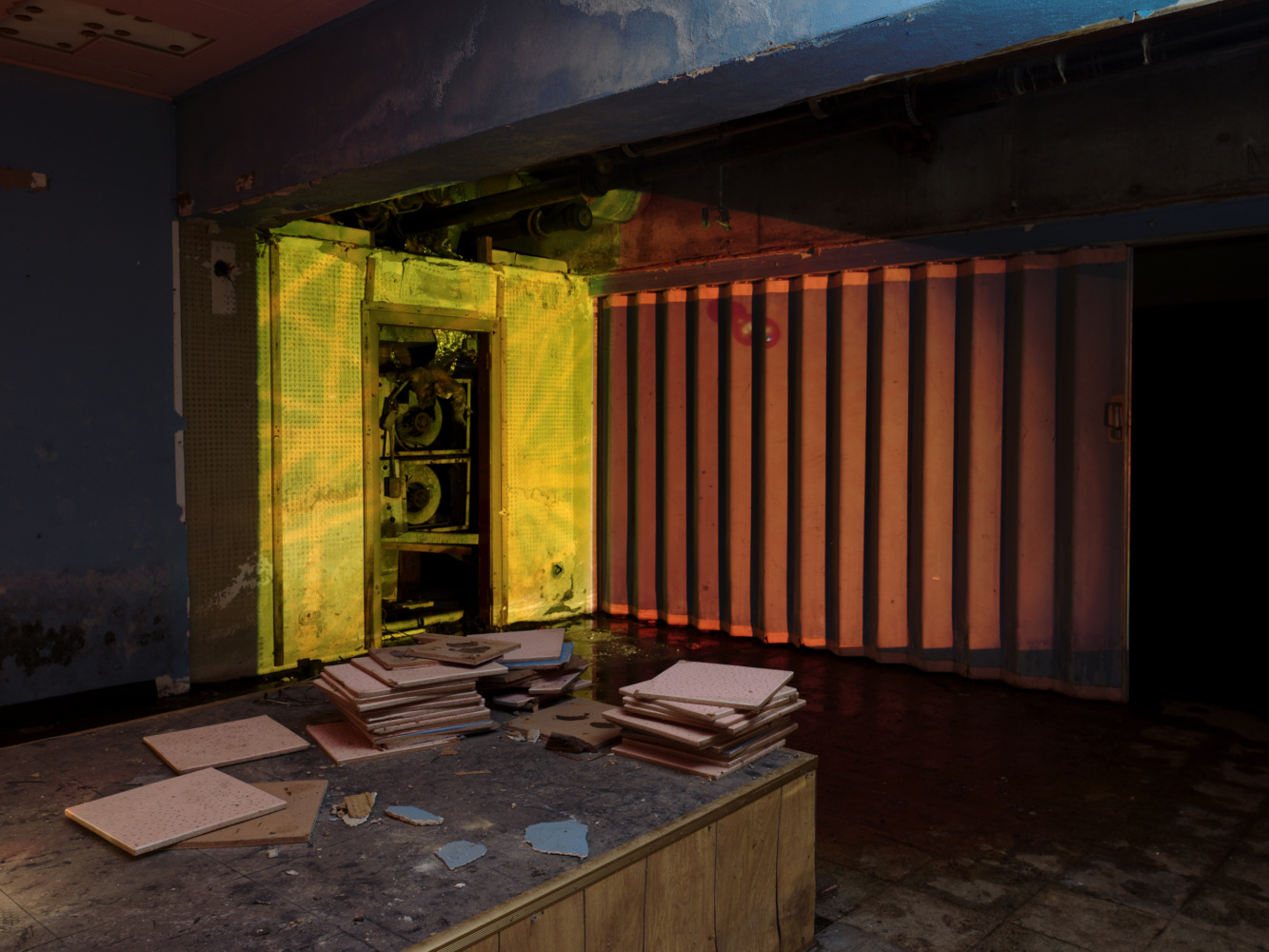

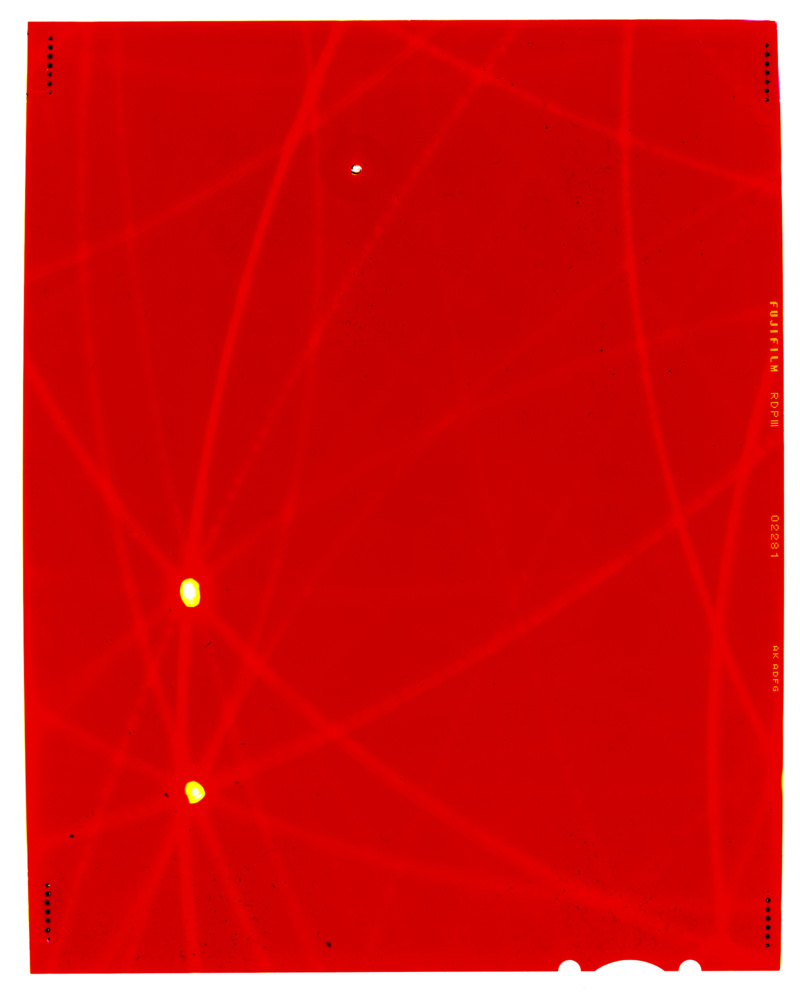

TE: In the series Baroque Sunbursts, you use lasers to expose the film, resulting in abstract, enigmatic images that are then projected onto the walls of a defunct nightclub. Could you share more about the alternative processes within this project and any other experimental processes you’re exploring?

JM: I often describe this process (as well as others) as being “dumb,” when I think I really mean “simple.” When I first started playing with these materials, I was struggling to photograph people dancing and clubs in a meaningful way, i.e. overthinking it to death. I had some 4×5 slide film that had been in my fridge for some time, and I did some experiments playing with it in the dark with a small collection of lights and disco balls. In hindsight it was very productive, in that it was fast and loose and not precious.

Some of the exposures seemed interesting, especially those with lasers, so I continued tweaking my approach and sending them off to a lab. It sat dormant for a while, and I returned to flesh out the work this spring. I used filters, tape, and mirrors to better control the light, as well as new lasers. One laser had a preset animation of a galloping horse, which felt like a funny [Eadweard] Muybridge reference—but also, who is projecting a laser horse?

When I returned to the work this spring, I got a ton of expired film on Facebook Marketplace and made a workflow for developing the film myself. It became both more precise and playful. I like using expired material, as it acknowledges time in a funny way; shining cheap lasers from the early aughts on film from the 1980s creates a dissonance that feels really rich.

I’ve also been working with printing gay pornography on expired paper, both lumen prints with magazines as well as projector experiments with bargain bin DVDs. It feels a lot like drawing, especially the projections. I like the ambiguity of their value, hovering between a precious vintage object and overly sentimental kitsch.

TE: You’ve mentioned that you like “using old things the wrong way” and gave the example of how Detroit’s abandoned Motown studios and equipment were reclaimed for early techno music (as described in DeForrest Brown, Jr.’s book Assembling a Black Counter Culture [2022]). Likewise—abandoned spaces, detritus, and the obsolete seem to form a kind of landscape and character in your photography and installations.

What are your interests in using abandoned materials and spaces, and what do they reveal?

JM: Why I am drawn to them in the first place is likely problematic, similar to Susan Sontag’s observation in On Photography (1977) that photographers are drawn to things often considered ugly or unusual. (I think she gives the examples of peeling paint and Diane Arbus, respectively.)

The materials come from extended observations of space, wanting to speak the language of the street or the club and respond to how images appear in these spaces. If a club has any images, they are often illuminated because it is dark; for example Wolfgang Tillmans’s rotating image install at Panorama Bar Berghain, or more generally the various TVs used as drink menus and advertising.

This is most obvious in my installation in the basement of Hawkins HQ, where I used 4×5 color positives on overhead projectors as a weird source of light, acting as a stand-in for a party laser while also being a direct exposure of one.

TE: In an earlier conversation we had about musical influences, you asked: “As something gains fidelity, what is ultimately lost?” That’s an evocative question that could be extended across multiple forms of expression: music, film, photography, etc. Are you working your way towards an answer?

JM: It’s such a dorky question, but I think it is applicable beyond an initial formal quality. It is easy to point at high fidelity as automatically artificial or composed. Beyoncé’s Renaissance (2022) was a really helpful cultural object for thinking through this; it’s IMAX dance music, house music for billionaires, maybe the most expensive dance record ever made.

I really like these questions, but I also resist the assumption that something of lower quality is automatically more true. Is taking a sneaky candid image more truthful than a very apparent image where someone can pose? It feels Freudian to separate these into a binary. I like José Esteban Muñoz’s definition of a queer ephemera, which pokes holes in the authority of an archive and instead emphasizes that which escapes it.

TE: What other questions are you exploring within the scope of your current projects and upcoming exhibitions?

JM: I’m looking at some notes from my exhibition that recently closed at Institute 193 in Lexington, Kentucky, and it’s maybe similar to my other curiosity but is also distinct: What is lost in excess or surplus? This also maybe explains my interest in strange and disregarded materials, that which is obsolesced. I don’t want to give the impression that I am saving these things or doing a noble service, but instead, I am interested in creating value where there was once none, which is a very reductive definition of art.

I’m also thinking a lot about American masculinity, something that has felt very oppressive in my life, but also, that I have benefitted from. I have no breakthroughs in this yet, though I’ve taken many pictures of my truck.