SEE CORRECTION BELOW TEXT, 10/8/14

The Zuckerman Museum of Art’s current group show, “Hearsay,” curated by Julia Brock, Teresa Bramlette Reeves, and Kirstie Tepper, is a smart follow-up to the museum’s inaugural exhibition “See Through Walls.” On view through October 25, “Hearsay” almost seems like a response to the controversy sparked by the university’s removal from that show of Ruth Stanford’s installation A Walk in the Valley,which critically engaged KSU’s acquisition of land once owned by lynching apologist Corra Harris. If that situation revealed the institution as a glass house, “Hearsay” presents ZMA as a nexus of conflicting stories, narratives, and histories.

“Hearsay” is a refreshingly thoughtful and dense show, packed with layers of narratives, histories, materials, and methods of exhibiting work. It features projects by solo artists and a collective, as well as installations curated by other organizations. Together, the installations create a South in multiplicity. Overall, the exhibition provokes the viewer to examine the ethnic, racial, and economic makeup of Atlanta and the region. In a sense, this show answers/further questions a topic addressed at a panel discussion at the recent 9/50 Summit at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center: “Does Regionalism Exist?”

Atlanta is rife with rumors and talk—its art scene especially. It is easy to forget that that world is in fact small and potentially, dare I say, insignificant to the broader city population. What is particularly apt about “Hearsay” is its engagement with “non-art”-related communities and projects. Arguably, these projects are more engaging and interesting than most of the “art” installations, with the exception of John Q’s Take Me With You and Nikita Gale’s 1961. This is one of the interesting aspects of “Hearsay”: its institutional boundary-breaking; its historical and archival installations pose questions as to what kinds of projects are relevant for an art museum.

One of the most compelling projects in the show is the Cherokee language installation curated by Adam Doskey of the Bentley Rare Book Gallery at KSU and Frank Brannon, who is a printmaking instructor in the Nantahala School for the Arts at Southwestern Community College in Bryson City, South Carolina. This project, which examines the development of the Cherokee Nation typeface and the newspaper Cherokee Phoenix, is a potent reminder of what came before and what was destroyed in order to make this region what it is today. However, the curators’ decision to present contemporary work in Cherokee language letterpress forces the viewer to recognize that it should be both possible and necessary for languages other than American English to exist in this country.

This pairs well with the Clarkston oral history and Photovoice projects, which catalogue the Georgia town’s refugee community, its experience, and that of local residents. Atlanta isn’t the best when it comes to accommodating an international community. It seems that the ITP and OTP divide is strict; according to census data, only about 8 percent of Atlanta’s population is foreign-born. What this project brings to light is the complicated tension of the international community with the more local African American community’s inequality. This conversation is thoughtfully engaged in “Hearsay” between this installation and two others: the After Malcolm Digital Archive project and Nikita Gale’s 1961.

Generally, the narrative about the Black Freedom Movement focuses on the impact of Christianity and Christian communities, centering on the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In a way, “Hearsay”’s presentation of the After Malcolm Digital Archive is a rejoinder to Emory University’s Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library’s (MARBL) exhibition “And the Struggle Continues: The Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Fight for Social Change.”

Collection of Louis Corrigan, Atlanta, Georgia.

So far, most of the work I’ve discussed has been of a historical or archival nature, so Nikita Gale’s evocative project 1961, which addresses the history of the Freedom Riders, is an excellent bridge to the more specifically “art” installations. Through the superposition and juxtaposition of images and text—collages of Freedom Rider mug shots and banal celebratory depictions of whiteness—dancing around a maypole in sundresses, for example, or boating; a letter to Malcolm X from the grand wizard of the KKK and a transcript of a speech by the Lt. Governor of Georgia—with an audio piece that is Gale’s vocal rendering of these textual artifacts, the artist creates a powerful experience of a particular historical moment. She speaks the words of these texts as if they were discrete objects without a proper narrative tying them together.

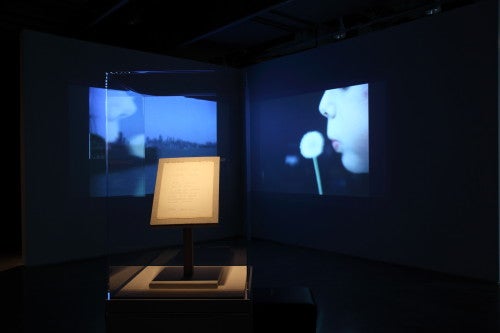

One of the other more successful art installations in the show is John Q’s Take Me With You, which addresses travel in the sense of queer migration to urban centers such as San Francisco. This project, following their 2013 project The Campaign for Atlanta: an essay on queer migration, similarly makes use of artist Crawford Barton’s archive that the collective discovered at the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society in San Francisco. Barton’s archive includes the documentation he had made in San Francisco’s Castro District as well as footage of his road trip there from Atlanta. Take Me With You is a pared down two-channel video installationthat includes Barton’s Super 8 travel documentation with John Q’s own footage of traveling on the road between Atlanta and Barton’s hometown of Resaca, Georgia. The two screens jump back and forth between the present and the past, without a boundary between the two. Another gesture of recreating the past in the present is John Q’s facsimile of a handwritten flier they found in Barton’s papers: “TAKE ME WITH YOU / I’M LOOKING / FOR A RIDE … / I CAN NOT AFFORD / GAS EXPENSES, HOW- / EVER, I’M YOUNG, / GOOD LOOKING AND / ALWAYS HORNY / 863-7136.” With this combination of materials, John Q offers the viewer a layered experience of time, space, and desire.

In a much different sense, George Long’s delightful outdoor installation and indoor video also engages with the palimpsest forging an intergenerational narrative and experience. The work, Flipping Translations, depicts weaves together Long’s childhood experience of the rural South with his son’s experience. Though the outdoor installation is completed, it no longer changes, the stop-animation video displayed in the gallery shows the process of creating the outdoor installation, which illuminates the layers of memory, action, and generations.

Carolyn Carr’s installation Still Life is one of the points of audience participation in “Hearsay.” The viewer is encouraged to respond to the installation by way of the written or spoken word; a notebook and audio recorder are provided. However, I’m not sold on the ways in which the audience is encouraged to participate, not on the part of Carr, the Zuckerman, or the installation of the After Malcolm Digital Archive. The rhetoric of audience participation in Carr’s statement and in the catalogue essay “Notes of Still Life” by playwright and KSU lecturer Margaret Baldwin Pendergrass included in the exhibition catalogue could speak for each of the instances of invitations to the audience. I appreciate the gesture of allowing the audience to participate in meaning-making, but these interventions do not seem meaningful enough. These responses function more as discrete afterthoughts than constitutive elements. It was confusing for this viewer which posted responses were we intended for what. At a certain point, the sea of words ceases to mean anything. However, the intimacy required to sift through the notebook’s pages brings the viewer more deeply into the work.

Strangely enough, a separate installation project that is also on view at ZMA by fiber artist Rowland Ricketts and sound artist Norbert Herber offers a more compelling engagement with materiality, landscape, and participation through the concept of quantity and necessary amounts. Titled Some Of Its Parts, this project encourages the community to participate in the cultivation and production of the artwork itself. Together with the KSU community, Ricketts and Herber grew indigo plants, dried them, ground them into dyestuff, and dyed fabric. This fabric hangs from the ceiling and creates layers of drapes that the viewer can walk through; it will later be used by the company American Colors. Enveloping this fabric is a sound work by Herber that is the sonification of data: temperature and color data sets. Each of the elements of the work is precise and nothing is wasted.

I’m still grappling with Robert Sherer’s I Know Where the Bodies are Buried, which is a quilt that illustrates certain individuals who are buried in the Marietta Cemetery. I’m very much into his use of blood as fabric dye, but I struggle with how the figures in silhouette read within “Hearsay.” It is difficult to not associate them with those of Kara Walker, which in a way is conceptually appropriate considering the sexualization and often violent demise of many of the individuals (Little Mary Phagan, JonBenét Ramsey, Dick Fisk) and the ways in which their histories are walked over. I prefer the documentation he provides in the exhibition catalogue instead.

Also in the catalogue is an essay on Margaret Mitchell, an Atlantan whose grave is still visited by tourists, by Jennifer Dickey, author of A Tough Little Patch of History: Gone with the Wind and the Politics of Memory (University of Arkansas Press, 2014), which includes a quote by Corra Harris, who was the controversial centerpiece of Stanford’s work in “See Through Walls.” I thought this a baffling choice considering the specific site and politics of the ZMA. I’m not exactly sure what to do with this choice. Is its inclusion representative of a mainstream historical imaginary?

“Hearsay” traces the complicated contours of this place where we find ourselves. It does not refrain from showing the viewer provocative and sometimes violent histories. Constantly negotiating the violence that rests just beneath societal infrastructure can be crippling. But this negotiation is crucial, which is why this show is an important contribution to Atlanta’s art, cultural, and historical ecology.

Meredith Kooi is the editor of Radius, an experimental radio broadcast platform based in Chicago. She is currently a PhD student in the Graduate Institute of the Liberal Arts at Emory University, a performance and visual artist, and a monthly contributor to Bad At Sports.

CORRECTION: In an earlier version of this review, the author mistook another installation as part of Carolyn Carr’s.