During the Apollo 16 mission, John Young and Charles Duke set up a gold-plated camera on the surface of the moon. Manually operating the camera-telescope hybrid, the astronauts collected 178 photographs that revealed invisible facets of space, focusing on Earth’s atmosphere, celestial bodies, and spectra. The fifty-pound machine, known as a spectrometer, still stands on Descartes Highlands, spending more than fifty years on the lunar surface. During this mission, the spectrometer registered far ultraviolet light that was previously invisible, opening a new swath of resources to observe and understand space.

The UV photographs made during the mission show Earth as an unstable collision of colors. A yellow, crescent-shaped core represents the half of the planet experiencing daytime, with green and red waves of light hazily surrounding the shape. Confining the array of colors, the background exposes a chaotic display of blue specs populating and energizing infinity. This background, in comparison to the cold and stable void we see in traditional NASA images, such as the “Big Blue Marble,” forces observers to consider the fragility of space, a delicate, but vast network of energy that suspends matter.

These images and their invisible data returned to my mind as I entered Fission or, Eclipse, Rose Salane’s exhibition at The Athenaeum at the University of Georgia in Athens. The main gallery is miserly lit, with few bulbs positioned to the center of the room, where a group of primary colored circular objects lay on the ground. Varying in size, the plastic shapes—some face up, some face down—compose a playful light exercise. A portion of them cast their colors on the floor, while others reflect them onto the room, acquiring a viscous quality, like watery eyeballs that have been open for too long. The circles are identified as decommissioned traffic lenses, used in New York City to signal vehicular pass before LED technology took over. Their rigid utility as traffic controllers mutates as they guide my movements through the gallery, inviting me to explore their light interactions in this newly formed maquette of a city grid.

Away from the bright center, but formally connected to the energy of the lenses, are five photographs hung on the furthest wall. Go (2024), shows a singular circle centered on the paper. Pulsating in blue green, it resembles the philosophical connotations of the “Pale Blue Dot” photograph made by the Voyager probe before exiting the Solar System; a fragile lonely spec that contains a reflection of an unknown force bigger than itself. Both images of flattened orbs share processes of alienation in dim environments. A traffic lens in a darkroom, or a space probe exiting the heliosphere are foreign elements that invite inquiry through obscurity.

The series of photograms, made by shining light through the decommissioned lenses, suggest myopic encounters. They position the viewer in front of a blinding happening; driving without glasses at night, or looking directly at an eclipse. I wish you could have seen them (2024) emphasizes the confrontational personality. It shows an exposure through three lenses, fenced by a pitch black background created by the uninterrupted reach of light onto the paper. In their core, the shapes hold dynamic energy, twinkling and expanding into a soft perimeter that engages one another through intersections of visibility and recognition. The constellation of circles resemble lights in recording machines, quietly tilting and surveilling the space.

Relationships with astronomical phenomena become humanized by four photogravures across the room. In each one of them the artist shows diary entries from witnesses of the annular solar eclipse visible in Georgia in 1865, the last year of the Civil War. The softness of the paper emphasizes Salane’s rigorous research as a practice of care. The entries offer a view into the writers’ past lives, describing mundane activities, weather details, and everyday thoughts of the four authors: a woman, a farmer, a soldier, and a child. Over these texts, Salane silkscreens red annotations to extract the personal encounters with the eclipse. The red marks carry the entries into the present, emphasizing snippets of their character, and the innate human excitement for light and obscurity, especially of celestial bodies. One witness describes the eclipse as “the moon with a bright ring around it”, while another one complains and notes that they have “seen a darker one years ago”.

In the second gallery—this one casted by natural light—I face six cardboard boxes stacked in two piles. Stickers, written messages, and printed text inform on their content, and a quick nearing reveals the careful arrangement of decommissioned traffic lenses inside of them. The lenses are vertically ordered, neatly deactivated by their storage and separation from light. The information in the two bottom boxes cleverly composes a poignant sentence, “Pedestrian Signal Buy American!”, suggesting a connection to the haphazard city map created by the circular pieces on the ground, which is now unreachable by my sight.

Externally, the cardboard shows marks of movement: old packing tape, a touch of bright orange spray paint, and many bends and creases point to its placement and displacement. The boxes are protected by a plexiglass case, making them both shield and content. As the softest and only opaque element in the composition, they experience relationships that challenge their preservation and utility.

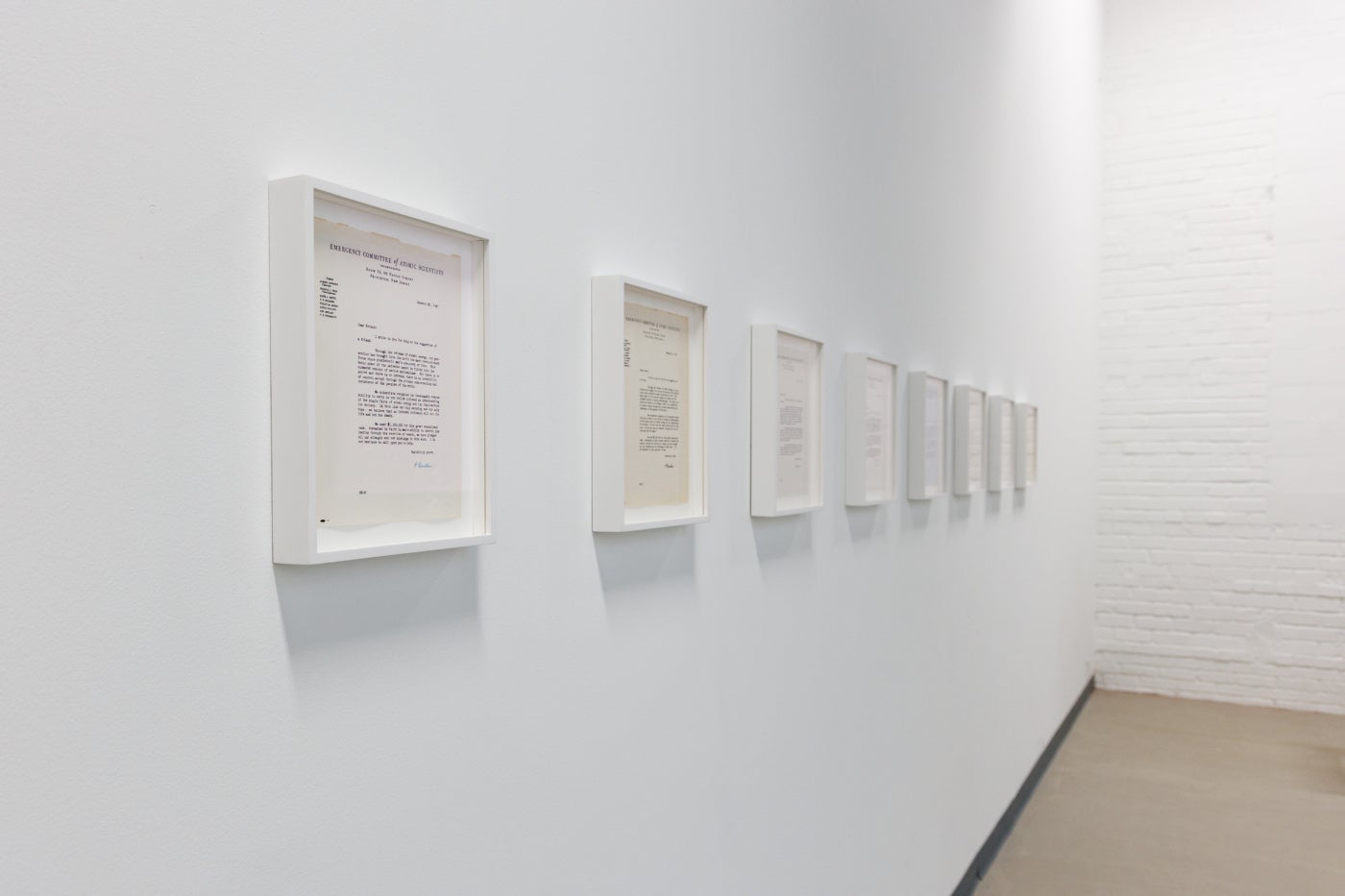

A suite of eight delicate letters hang next to the storage arrangement. Each is printed on a slightly different color paper, but with almost exact content: a reproduction of a card by Albert Einstein, as part of the Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists. The letters were sent to different academic institutions in the U.S. to request funds towards nuclear and atomic energy research. They mention how these educational efforts are “sustained by faith in man’s ability to control his destiny through the exercise of reason”, contradicting the colorful ruins at the nucleus of the exhibition. Here, Salane envisages the forces and systems molded by humans. Presenting an ecosystem of positive cynicism, she uncovers elemental aspects of humanity through polar states of material preservation.