“The camera eye is more perspicacious and more accurate than the human eye,” French filmmaker Jean Rouch once said, and his idiosyncratic documentaries, which were often fusions of reality and fiction, bear this out. Using a handheld camera when it was still a rarity in filmmaking during the late 1940s, Rouch became internationally renowned for his short films on African customs and rites, with Mad Masters (Les Maîtres Fous, 1953), a document of the Hauka possession cult in Accra, Africa, often singled out as a key work.

Although relatively unknown to American moviegoers, Rouch was a figure of great interest in academic circles and anthropology groups, and extremely influential on the Nouvelle Vague and experimental filmmakers of the ’60s. Thanks to Andy Ditzler of Film Love, Atlanta audiences will get a rare opportunity to view Rouch’s Jaguar on February 19 at the Atlanta Contemporary and discover why the filmmaker is considered such an unconventional master of the ethnographic form.

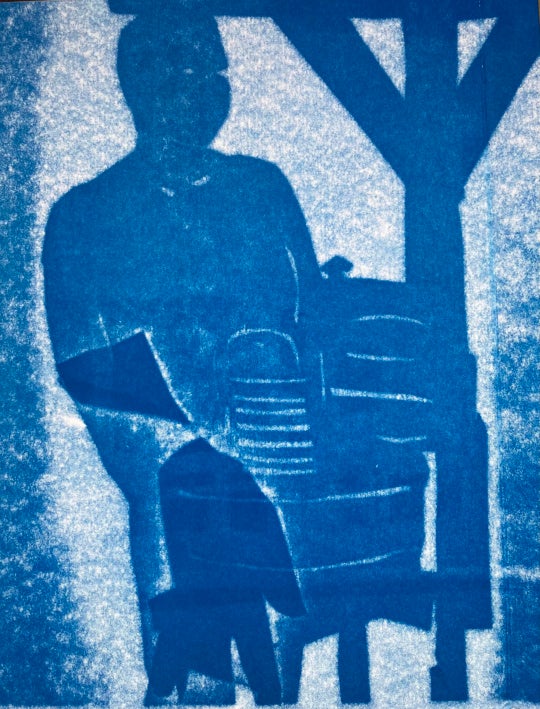

Jaguar is a cinematic journey by three young Nigerian men who travel from their village to the Gold Coast (modern day Ghana) in search of work and adventure. But unlike the traditional methods used by documentarians like John Grierson and Joris Ivens to convey realism, Rouch made his three subjects complicit collaborators in the filmmaking process. “It was shot as a silent film,” Rouch stated, “and we made it up as we went along. It’s a kind of journal de route – my working journal along the way with my camera. We were playing a game … I brought the film back two years later and projected it to the boys in Accra. We improvised the commentary in one day.” The result is an original work of art in which the three principles alternate between playing themselves and fictitious alter egos.

“You don’t know when they’re intentionally pulling your leg,” Ditzler comments. “I wanted to show it partly because it is very subversive in and of itself. It also takes place against the background of revolution in Ghana; Kwame Nkrumah is coming to power at this time, and you actually see CPP (Convention People’s Party) rallies in the film. It’s not just dropped in as a point of interest. You’re well aware that a revolution is going on at the time they’re filming.”

Not everyone was enamored of Rouch’s work. African director Ousmane Sembene accused him of studying his subjects in the manner of an entomologist, and some critics complained that, as a European with ingrained colonialist ideas about Africa, his viewpoint was compromised. Yet Ditzler points out that Rouch was subverting ethnographic conventions in films like Jaguar. He was addressing issues like “how do we deal with the fact that we’re filming people and being self-reflective about inserting the filmmaker into the film. And making sure everyone knows this is a film.”

Rouch was the antithesis of the stereotypical Westerner who traveled to Africa to steal images and then retreated to a place of safety. He was “way ahead of the curve on that,” Ditzler notes. “He’s wickedly humorous and was deliberately constructing fictions. The films are very much collaborations. They’re critical and playful at the same time.”

Jeff Stafford writes about art, film, music, gardening and other favorite topics for various digital publications.