As an artist and social activist, Carrie Mae Weems’s consistently evokes an intensity and intimacy through photography, film, and written narrative. Weems, a MacArthur fellow and the first African-American woman to have a solo exhibition in the Guggenheim, refuses to condone any kind of glossed-over version of United States history, and in her work asks the viewer to confront the legacy of the slave trade, the erasure of black celebrity by white narratives of popular culture, and police brutality of today. At Hammonds House Museum in Atlanta, Weems’s photographic series From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, along with selected works and her 2016 film People of A Darker Hue, demonstrates the artist’s strength as a storyteller, and as a powerful voice against racism, white nationalism, and the white-washed narrative of our country.

For From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, Weems rephotographed and enlarged rare 19th- and 20th-century photographs of enslaved people along with free black men and women. Borrowed by Weems from museum and university archives, many of the daguerreotypes were originally commissioned by Louis Agassiz, a Swiss naturalist who intended to use the photographs as evidence in support of his theories of white racial supremacy. By appropriating the photographs, reimagining them, and adding new phrases to the images, Weems seeks to give a “voice to the subject that historically had no voice.” It wasn’t an easy project — when it first debuted in 1995, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology threatened to sue Weems over her use of some of the photographs taken from Harvard’s archive, though they eventually relented. In an ironic twist, Harvard ended up actually purchasing some of the series for their collection, and is considered one of the most important moment’s in Weems’s artistic career.

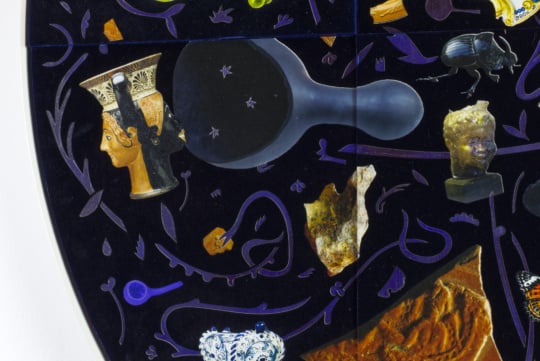

The red tone of the photographs, along with the circular black border, evokes images such as those seen from under a microscope. This presentation functions as a visual reminder of how the men and woman in the photographs were treated as biological subjects, rather than real people. The viewer is meant to move through the exhibition, reading each piece as if a line from the same poem, starting with a large, blue-toned picture of a woman, with the phrase “From Here I Saw What Happened” etched across the glass frame. She is the prime witness of history, and her gaze beckons the viewer to stand witness as well. In the first room, phrases are etched on top of the photographs’ glass frame, such as “You Became A Scientific Profile,” a reference to Agassiz’s racist research, and “House / Yard / Field / Kitchen,” the specific designations of where slaves belonged on the plantation . The series ends with the same image of the blue-toned woman, but flipped, this time with the caption “And I Cried.” Through their size and presentation, Weems’s works lay bare the inhumane treatment inflicted upon enslaved people and their descendants. But while the images are harrowing in many ways, Weems also treats the portraits with a kind of fierce remembrance.

While From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried is the focus of the exhibition, three selections from the series Slow Fade to Black are worth noting. The intentionally blurred images of Josephine Baker, Lena Horne, and Katherine Dunham draw attention to the erasure of famous black woman from mainstream history. “I started to realize that I rarely heard mention of these women,” Weems once said to the New York Times. “Unless, I was playing them on CDs in my own home, I didn’t hear them or see them much anymore … They are disappearing, dissolving before our eyes.” The photographs are so blurred that you cannot tell who is who, though their glamorous poses under the spotlight and shimmery outfits conjure a sense of familiarity. They are the visual representation of a fading memory in a collective consciousness.

Weems’s 14-minute short film People of a Darker Hue plays in the small upstairs area of Hammonds House Museum. Unlike the photographs on the lower floor, the video takes the viewer onto a contemporary stage. With tenderness, Weems uses the film to focus on victims of deadly police violence. Through footage of black people walking city streets, a young black boy running on a seemingly nonstop treadmill, and a voice reading aloud the names and ages of victims of police violence, Weems creates a powerful and thought- provoking meditation on death and the daily, repetitive struggle to survive in America.

Weems’s photographs and film work together to expose a violent history in order to increase an understanding of our present. From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried & Selected Works is up through April 29 at Hammonds House, and is a monumental must-see for fans of contemporary art.

E.C. Flamming is an Atlanta-based writer. She has been published in ART PAPERS, Paste, ArtsATL, and The Peel Literature & Arts Review.