Whether masked by multiple neckties, erased by razor-gashed patches of white paper, or simply turned away from the viewer, nearly all the faces in Jamaican-born artist Cosmo Whyte’s exhibition “Starting a Bush Fire” at Marcia Wood Gallery are somehow obscured or transfigured. In the large charcoal drawing Kiss Mi Neck Back, a figure’s scalp appears to outgrow its conventional anatomical boundaries, spreading across the skull so that only a single ear remains visible amidst sections of parted hair and an elaborate bundle of braids—impossibly illustrating the exclamatory Jamaican phrase from which its title is taken.

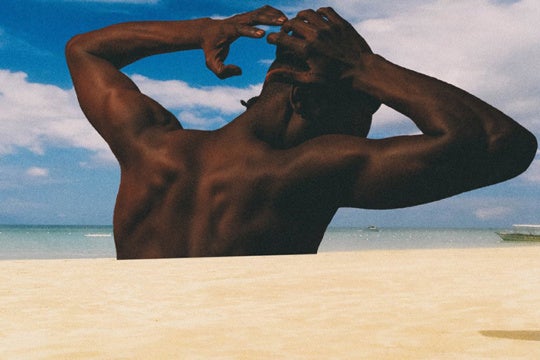

Another drawing, Cheaper to Keep Her, is based on an archival image of Princess Margaret in a motorcade during her visit to Kingston to mark Jamaican independence in 1962. While indistinct smudges conceal the faces of the uniformed young women standing alongside the motorcade, Princess Margaret’s face is more dramatically altered, seemingly ripped in broad slashes from the paper’s surface. Even when using images of himself, as he does in the richly printed photographs Stranger Than the Village and Heirloom 3, Whyte refrains from showing his face to viewers. But Stranger Than the Village is also the exhibition’s striking exception, as it reveals an image of a recognizable face: that of writer James Baldwin, pinned to the back of Whyte’s suit jacket, his eyes almost appearing to follow the viewer as they move through the gallery.

Whyte’s work contains layers of critical and historical reflection that feel idiosyncratically human when rendered with this level of precision and tenderness. The titles of works throughout the exhibition provide a sense of the breadth of Whyte’s research and reading, ranging from Jamaican patois phrases to allusions to the work of writers such as Baldwin and V.S. Naipaul and the 1967 film Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. Taken altogether these reference points contextualize Whyte’s work across multiple continents, centuries of the African diaspora, and generations of migration, but the resolution of the figures he presents always appears to be morphing and changing. Whyte suggests that this mutability of identity is partially the product of historical forces but also investigates it as an issue of self-perception and self-representation. In “Starting a Bush Fire,” it is not only the stranger who is foreign to you but also yourself.

Comprising most of the exhibition, his drawings are distinguished (in the most unabashedly old fashioned way) by their sheer technical virtuosity and bravado; some of the braids in Kiss Mi Neck Back are almost photorealistic. Many of Whyte’s formal choices are the same that have characterized his drawings for years, including scraping the surface of the paper to produce what he refers to as “keloids,” or scar tissue, and detailing the images with gold leaf.

While staying faithful to a limited trio of tools—paper, charcoal, and gold leaf—Whyte has also introduced a new element to his drawings, delicately cut patterns along the paper’s edges. These lacy-looking details appear at the corners of the drawing Vessel 2. Through shadows and repetition, it shows four slightly different perspectives on the same solemn face floating above a gray oval expanse encircled by disembodied arms and fabric. The negative space encompassed by the figure in Vessel 2 lends itself to varying interpretations: it could be a body of water such as the sea, or instead the vast sky used by navigators to chart routes across that water. (Notably for Whyte’s work, this sort of celestial navigation would have been employed by both sailors engaged in the transatlantic slave trade and runaways along the Underground Railroad.) Viewed between the two drawings displayed on either side of it in “Starting a Bush Fire,” Fi we boat must reach and 18.9712º N, 72.2852 º W, the shape of the image in Vessel 2 can also appear like the central landmass in a small archipelago of three islands in a vast sea of white walls.

The lacy patterns cut into some of the drawings in the exhibition mimic the design of the knit doilies in The Enigma of Arrival in 4 parts. Part 2: “Carrying On,” one of two sculptures in the exhibition. Made of a row of three airline seats that have been reupholstered to resemble a kitschy, grandmotherly sofa, “Carrying On” is another instance of wordplay, joking about baggage as well as the popular British wartime phrase. Whyte’s second sculpture, The Enigma of Arrival in 4 parts. “Guess Who Is Coming to Dinner,” creates an even more surreal image: an enormous mass of dozens of fluorescent life jackets encrusted with blue-winking mussel shells. It is the first work you see upon entering the gallery, which is only worth noting because of its pointed installation. Hung high at the entrance, the jackets appear as if viewed from below, underwater perhaps. Though in a different medium, it shares the same surreal sensibility of Kiss Mi Neck Back.

In “Starting a Bush Fire,” Whyte achieves a remarkable balance between history and metaphor, aided in no small part by his artistic vision and considerable talent. To see an artist work with such conceptual rigor and emotional sensitivity using nothing but paper and charcoal—and, occasionally, gold leaf—is astonishing, a sensory delight and intellectual challenge.

“Starting a Bush Fire” is on view at Marcia Wood Gallery through November 25.