The compelling exhibition “Black Chronicles II,” which ends its run at Spelman College Museum of Fine Art on Saturday, May 14, brings together over 100 photographs primarily drawn from the Hulton Archive (Getty Images) as well as private collections. The late 19th-century black-and-white studio portraits from Great Britain include rare albumen prints, cabinet cards and small cartes-de-visite (2½-by-4-inch calling cards). These are a rare find, as photographs of this community are not readily found in other documentation from that era. The faces on the walls act to amend the historical record of Great Britain.

For the first time since the 2007-08 show “Cinema Remixed & Reloaded: Black Woman Artists and the Moving Image Since 1970,” Spelman’s gallery space is completely transformed. The walls are painted a semi-flat black, creating an amazing theaterlike experience for the viewer. Walking through the tight, black, hallway that leads into the gallery is akin to being an explorer, a modern day Indiana Jones, who shimmies through a small space only to make an amazing discovery: an opening filled with rare jewels and amazing artifacts.

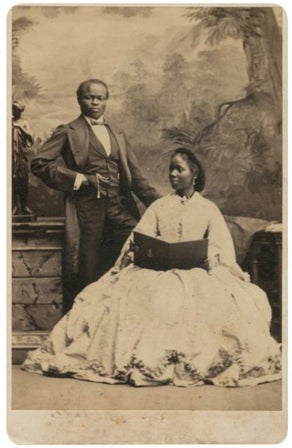

Texture, contrast, depth, and detail abound in these alluring and intriguing images. One of the most amazing elements of the works is found in the faces of the sitters. The photographs depict blacks (African and Asian) in Great Britain during the Victorian and Edwardian periods. They include dignitaries, servicemen, missionaries, performers, and others – some are known yet many remain nameless. Included is Peter Jackson, the world famous bare-knuckle boxer who was also known as “The Black Prince.” There are also images of Kalulu, the personal servant and companion of British explorer Henry Morton Stanley, dressed in what might be considered typical African attire in one sitting with Sir Stanley and dressed in more typically Western attire in another.

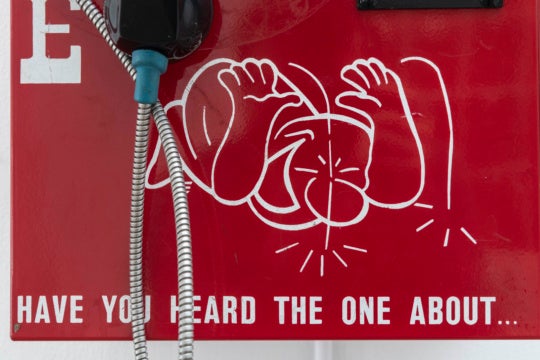

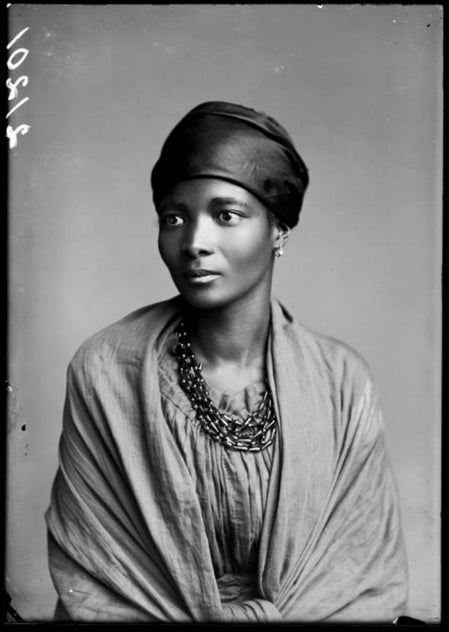

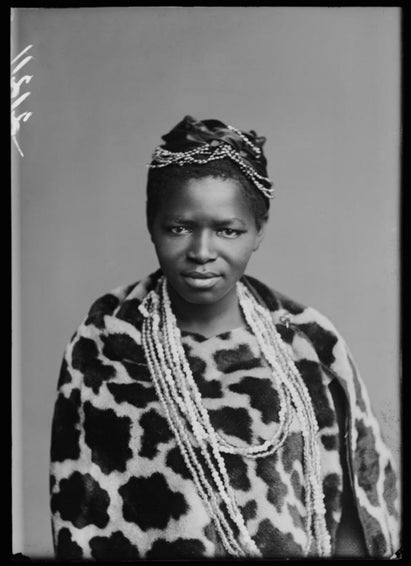

Most impressive are the approximately 30 exquisite, life-size photographic portraits of the African Choir, a 16-member ensemble from South Africa that toured Great Britain from 1891 through 1893 to raise money for a technical school in their country. In contrast to the many smaller works found on the left side of the gallery, these large portraits meet one head-on upon entering the gallery. Immediately, one is struck by the detail found in the photographs. The texture of the sitters’ hair as well as the topography of their skin are easily discerned. They are dressed in what might be considered native attire: scarves, animal skins and beads. Interestingly, in a small group photograph of the choir just to the right of the entrance, the choir poses in their “native” attire with their two Caucasian sponsors on either side. Lying in front of the group are animal skins. In the center of the group, a female choir member is captured with her head in her hands, covering her face, as if she is crying. There seems to be something wrong, but exactly what is not discernible.

The large prints (most are 42½-by-31½ inches) were recently produced via traditional processes straight from the original 19th-century glass plates by one of Great Britain’s most celebrated master darkroom printers, Mark Spry, who was summoned out of retirement to handle the delicate project. The clarity and detail are remarkable. The images usually are not seen on this scale. Their impact is unexpected from plates of their age, found wrapped in paper and string lying untouched for over 125 years.

Most of these works were unearthed from the Hulton Archive’s London Stereoscopic Company collection, now a part of Getty Images. These are the gems of the pioneering Autograph ABP (founded as the Association of Black Photographers in 1988), a London-based organization that seeks “to address the lack of visual representation of Britain’s diverse communities in cultural history.”

As Autograph ABP Curator and Head of Archive Renée Mussai said in an interview in ARC (Art. Recogntion. Culture), “Our curatorial work in the archive is driven by this notion of the Missing Chapter, and a desire to remediate ‘archival lacunae’ – to address/redress the many gaps inherent in the cultural history of photography, here as well as elsewhere.”

As one explores the gallery, it is easy to only glance into or walk past the small chamber that includes Dawoud Bey’s photographic diptych of Stuart Hall, the noted cultural scholar, pioneer of semiotics, and past chairman of Autograph ADP. But don’t! The show is dedicated to him for a good reason. Inside, an audio recording anchors the exhibition with an approximately 20-minute excerpt of Hall’s keynote lecture from the symposium The Missing Chapter: Cultural Identity and the Photographic Archive (London, 2008), in which he speaks to colonization, globalization, and marginalization. Several quotes from Hall can also be found high upon the walls of the gallery space. These quotes along with the lecture help to contextualize the photographs and provide the curatorial framework for the exhibition.

Hall was a pioneer in semiotics, the study of the encoding and decoding of meaning in text and images, and the works in this exhibition beg to be decoded. What does it mean that the South African choir was dressed in “primitive” attire? Is the woman in the group photograph crying because she feels like the victim of a cultural heist? In fact, the African Choir comprised business leaders, educators, men and women who would go on to be in the vanguard of social change in South Africa at the turn of the century. Along with the photographic plates, the archives hold written exchanges between members of the choir and members of their South African community about the rugs and clothes their “handlers” had them wear to make the sitters seem more “African.” Significant discussions ensued regarding the image that the choir was projecting of their fellow South Africans. It was incomprehensible for leaders back home to believe that the choir, wearing those contrived outfits, was projecting the educated, dignified and respected image they intended.

The masquerade was the ill-conceived solution to the choir’s not filling up venues and bringing in as much revenue as had been hoped. Their sponsors’ idea was that the “African” attire would make them more intriguing to the public and boost attendance (unsurprisingly, they were correct). Perhaps the female choir member whose photograph was captured with head in hand was feeling exoticized like the Hottentot Venus, Sarah Baartman, a fellow South African, who had been been put on display in freak show attractions across Europe less than 100 years earlier. Perhaps the dour, forlorn, and joyless expressions on the faces of the choir members was their coded way of letting others know that they were not complicit in this demeaning deed.

As one of the Hall’s quotes on the wall states, “There’s nothing like a photograph for reminding you about difference. There it is. It stares you ineradicably in the face.”