Artist Bethany Collins’s Evensong presents poignant subject matter and thoughtfully arranged artworks that create a compounding intellectual experience. The exhibition shouldn’t be rushed through for a quick glance. It requires sensitivity and benefits from close observation. While the details of her work come through clearly in digital images, experiencing the works’ contrasting scales, exquisite craftsmanship, and harmonies within the installation can only be done in person. Collins’s poetic gestures applied to historical hymns, ancient tales, and archival clippings inspire copious associations to contemporary issues such as war, racism, and activism.

In The Star Spangled Banner: A Hymnal, Collin’s skillful edits to sheet music highlight a dissenting perspective on war. In this work, she references an early American approach to activism through contrafactum, a practice that combined iconic patriotic tunes with revised lyrics themed on causes such as labor, suffrage, and American values. The page on display comes from Collins’s artist book, and is shaped and sized like a standard, Presbyterian church hymnal but does not function like a text in a church pew. Collins precisely burned away musical notations with a laser cutter. Divorced from the melody, the phrases cannot be sung, and the language remains as poetry to contemplate. The lyrics by Katherine Devereux Blake begin: “O say can you see you who glory in war, All the wounded and dead of the red battle’s reaping?” Blake’s text offers a critique of war and American patriotism that is grounded in violence that the National Anthem amplifies. The language speaks of longing for those in power to consider the personal losses begot from war.

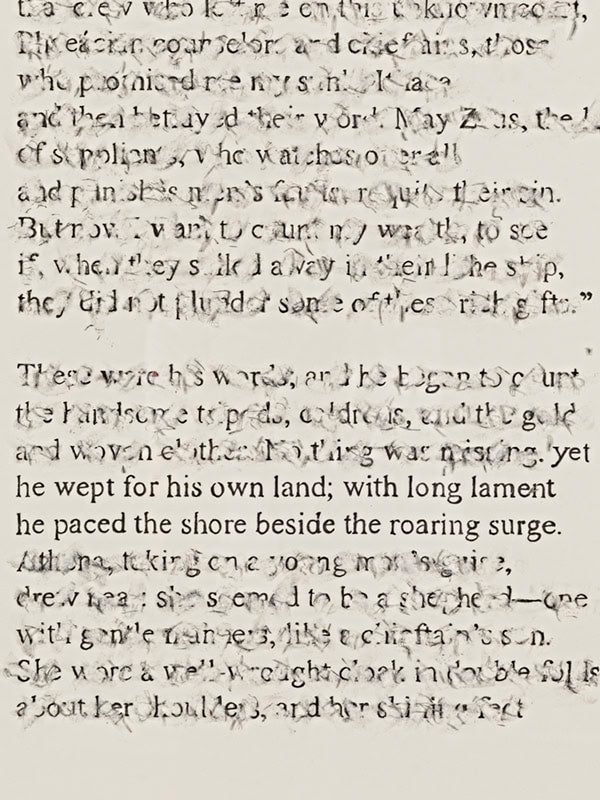

Collins offers the subject of war and its residual disasters again in The Odyssey: 1990 / 1851 / 1980 / 2002 / 2000, 2020. The series of large-scale works on paper presents different translations from Chapter 13 of the ancient Greek epic poem The Odyssey. In these selections the hero, Odysseus, does not recognize his homeland after ten years fighting in the Trojan War followed by a decade-long treacherous journey home. The repetition and subtle differences in phrasing presented in her work reveal a historical record of people passing down this story and accommodating the language to their contemporary sensibilities. Collins joins this tradition of bringing the story to a current audience, but rather than translating, she offers a critical point of view.

As with The Star Spangled Banner, Collins activates language through erasure in in The Odyssey: 1990 / 1851 / 1980 / 2002 / 2000, 2020. Applying her saliva to the surface of the paper and scrubbing until it wore away, Collins makes highlighting meaningful passages a visceral experience. The rough markings that obscure precisely chosen parts of words is physical evidence of her obsessive labor. Collins took great care creating the hand-inscribed texts, and the expressive gestures she applied to them indicate unrest.

The poetry Collins crafts through her edits conveys confusion, urgency, and yearning. One segment shows Odysseus’s desperation: “he wept for his own land; with long lament he paced the shore beside the roaring surge.” Taken out of its original context these words indicate the alienation that comes with being lost in foreign land. I thought of the questions around patriotism I had gathered from The Star Spangled Banner and reflected on the internal battles creating fissures in the United States today: armed conflicts, divisive politics, systemic racism, and climate change. I feel empathy for people facing estrangement from their land and culture. Another work in the exhibition, Help me to find my people, provided an additional level to consider disconnection, the loss of family.

Help me to find my people also contains elements of violence and yearning from the past that continue to impact life today. Unlike The Star Spangled Banner and in The Odyssey: 1990 / 1851 / 1980 / 2002 / 2000, 2020, all of the text in this series of eight wall-hangings was obscured and required effort to engage with. Embedded in the black embossed surfaces are references to ads placed by formerly enslaved people trying to connect with their loved ones. The visual conflict of trying to read the text on the low-contrast image echoes the struggle to truly engage with the under-acknowledged sadness, ruptures, and despair that stem from America’s history of racial violence.

The title’s imperative statement is especially painful when considering the limited chance of reunion families separated by enslavement faced. The clippings reveal the writer’s sincere desire to reunite, and also contain vague descriptions resulting from years of displacement and bondage. One clipping reads: “I am anxious to hear of my child and also my parents named George, Randy, and Cindia. My name was Rachel Parsley. George was six years old…I was sold to a man named Davis, who sold me to Mr. George Ricks, who brought me to Texas 29 years ago.” Relating the title of the work to its content reveals a tragic part of American history, and like the other works in the show the implications extend into the present. Reflecting on families separated at the US-Mexico border or the current incarceration rate that affects Black families disproportionately, it is clear that systemic brutality endures.

In Evensong, works from different series come together to speak in communion. Collins engages texts from the past and gives evidence through her gestures that the issues they uncover are still alive. I commend Collins’s commitment to providing more robust histories of the United States through her art. When seeing them, particularly as a show, the meticulously crafted artworks offered critiques that weighed heavily on my heart. An evensong is a service of evening prayers, and like a spiritual ritual the show creates moments of solemn and honest reflection. References to the human fascination with war, the struggle to identify home, and the atrocities that humans enact on each other forced me to grapple with contemporary reality. Feelings of longing, mourning, and confusion pervade the exhibition, but rather than only condemning, the artworks provide insightful encounters that could spark reforms.

Bethany Collins’s Evensong is on view at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, Tennessee through September 12, 2021.