When he was about three years old in the late 1940s, Charles Gaines asked his mother if he would come back as a bird after he died. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, even as a young boy, Gaines understood on some gut level that racist Jim Crow laws structured the South, that he and his family were the segregated subjects of this system, and that one of the few means of escape was not being a Black human. As an artist, Gaines spent the first stage of his career using rule-based procedures to produce grids, combining photographs and works on paper to break down representations of Black figures and trees into a series of numerical squares. Though not overtly political—a fact that resulted in his exclusion from the canon of conceptual artists for many years—his work hinted at the organizing structures of race and environment.

Gaines’s mid-to-late career, as surveyed in Charles Gaines: 1992–2023, at the ICA, Miami, illustrates his turn to a more explicit approach, though the works can still retain a sleek obfuscation that provides the audience with more questions than answers. His work is still about how we know what we think we know: As Franklin Sirmans wrote, Gaines was “a part of the 1970s generation of artists for whom the crossover between studio and the seminar is a crucial facet of their work.” Moving from theory into a more explicit politics, from the 1990s through today, Gaines has provoked questions around identity, power, planetary crisis, and how we measure these ideas. Gaines manifests the way-too-elegant and reductive positions that humans develop from the chaos of entangled images, narratives, data points, and feelings. His artworks are also, simply but crucially, beautiful to look at.

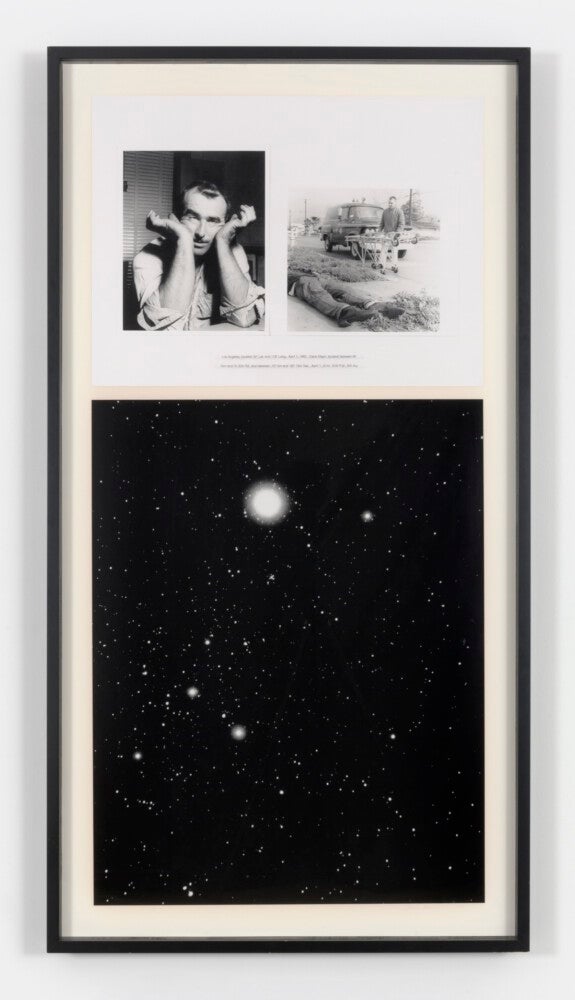

Charles Gaines, Night Crimes: Canis Major, 1995, photographs, silkscreened text on acrylic, 70 3/4 x 37 3/4 x 3 inches. Photograph courtesy of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Miami, Miami, Florida.

The exhibition includes Night/Crimes, a series started in 1994, where Gaines pairs photographs from the LAPD and Los Angeles Times archives of grisly crime scenes next to images of a person convicted of murder (Gaines has lived in Los Angeles for many years, and recently retired after more than 30 years on faculty at CalArts). Below these evidentiary, journalistic images are photographs of a night sky, the stars positioned as they would have been on the exact night of the murder. The effect is a sense that these things are related, that there is some kind of cosmic, fated relationship. Though an avid reader of horoscopes, Gaines has said he doesn’t believe that celestial bodies have any bearing on human behavior. And the alleged murderers depicted? They didn’t commit the crimes. At least, not the ones pictured. Acting like an unreliable narrator trying to show us a deeper truth, Gaines uses the incongruence to point out our own assumptions of causal relationships amongst elements, a sense that representative art always reveals something called “reality.”

Airplanecrashclock (1997/2007) is a tabletop diorama. Affixed to a thin pole, a little airplane flies over a model cityscape composed of a smattering of iconic buildings from different American cities, including New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Eventually, the plane takes a nose dive; screaming can be heard. A panel in the diorama flips, the plane disappears into the guts of the sculpture, and the site of a plane crash is revealed. On the base of the sculpture, there is a round wall clock. Crisis and tragedy aren’t only markers of time—originally made before 9/11, Gaines added the Freedom Tower later—they establish, reinforce, and upend power dynamics. Another one of his “disaster machines,” Falling Rock (2000-2023), consists of a tall glass and wood tower with a clock at the top. In the middle of the tower near the top, a 65-pound hunk of granite hangs menacingly. From time to time, the granite drops and smashes a pane of glass at the tower’s base. I was sad to not experience it during my visit.

Though a lot of his work deals with the messiness of catastrophe, there is a cool precision to his post-minimalist aesthetic that is orderly and obsessively clean. But this precision is deceptive. As Gean Moreno, curator of the ICA exhibition, remarked, “It’s an idea that the system should be getting between you and the work, as opposed to producing this work that is so perfect that you don’t have to think about it at all.” Gaines’s Faces series, started in 1978, includes headshots of people overlaid with acrylic panels that contain painted grids. Letting a systemic approach guide the work, Gaines assigns different colors to different aspects of the face. The result is a ghostly yet vibrant apparition that is also a map of arbitrary difference. Once closer to the Faces, you can see the painstakingly hand painted numbers on each of the many, many squares that make up the grids.

The Faces included at the ICA are from 2018. The selection includes various political figures and thinkers, such as Karl Marx, bell hooks, and Edward Said. The use of these firebrand leftists might agitate some audiences, especially in Miami, but they’re an example of a counterintuitive process: the depoliticizing effects that explicit politics can have on art. A later series of Faces, from 2021, included people who self-identify as mixed-race. A provocative critique suggesting that the category of mixed-race relies on the notion of racial purity to begin with, this series accomplishes more of what Gaines does so well: poking holes in the pre-programmed narratives that audiences view art with. Sure, there is so much more to these thinkers and figures than our typical associations of them, no matter our ideological commitments. But more pressing political questions are raised by the use of strangers than the use of these iconic figures.

Charles Gaines, Numbers and Trees: Charleston Series 1, Tree #3, Boone Hall Drive, 2022, acrylic sheet, acrylic paint, lacquer on wood, 60 x 82 7/8 x 5 3/4 inches. Photograph courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Miami, Miami, Florida.

There is an interesting question at the heart of the exhibition. Has Gaines’s work become more political, or has our sense of what counts as political caught up to his understanding? The works in the show represent the last thirty years of Gaines’s career. At 80-years-old, Gaines is still pushing people to question deeply held assumptions. Started in 2020, his Numbers and Trees series at the ICA are like the Faces series: starting with a photograph of a tree, he then overlays methodically painted, numbered grids of the tree on top. Though more recent, the work harkens back to some of Gaines’s earliest work, especially the Fallen Leaves series, from the late 1970s. At first, they might seem like simple landscape works with a conceptual twist. The belief that people are political animals is an idea that goes back to Aristotle. But that a tree is political—this awareness is far more recent.

Charles Gaines: 1992–2023 is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) Miami in Miami through March 17, 2024.