Blame language for its inability to be more nuanced. Blame language, because the best term to describe California artist Marlon Mullen’s work should be art brut, the term coined by Jean Dubuffet that translates as “raw art.” Blame language because, as Americans, we all too often define terms literally and see brute in the word brut, as if art brut literally meant some practice preferred by a pugilist with two hams for fists.

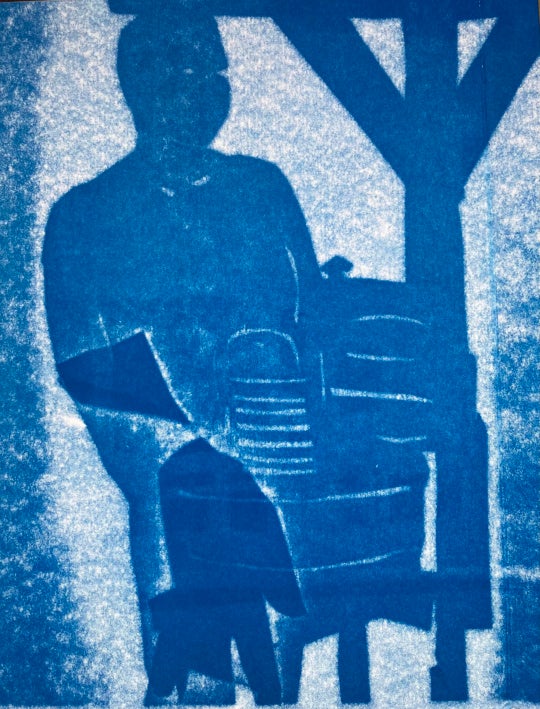

I begin here because Mullen’s exhibition at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center deserves to be considered with a sense of remove. It deserves to be detached, to be severed from a literal connection to its source material. As installed, Mullen’s paintings, which all begin as advertisements in popular art, design, and homes magazines, are anchored by a display case featuring the precise pages from which their inspirations are drawn. The concern is that this creates a sort of “compare and contrast’” where what is included or omitted is as significant as what the work itself contains.

Of course, all art is a process of interpretation. It may be the interpretation of an object, or it may be the interpretation of an idea, but somehow in the former there is a tendency for reduction and, in the latter, for celebration. I also say this because in what other context would appropriation be so obsessively chronicled? What I mean here is that in some sense Mullen becomes situated in an indeterminate space where his works are contemporary enough to transcend the strictures normally attributed to “pure” folk, if such a thing exists, yet not quite conceptual enough to be truly postmodern. This is a difficult conundrum.

So the challenge with Mullen’s exhibition — and this is not so much a criticism as it is a recognition of the challenge art organizations face when contextualizing equivocal works— is that there is no sure way to position his practice within a wider critical discourse. As a result, approaches like providing explanatory source material serves to ground the project in familiarity.

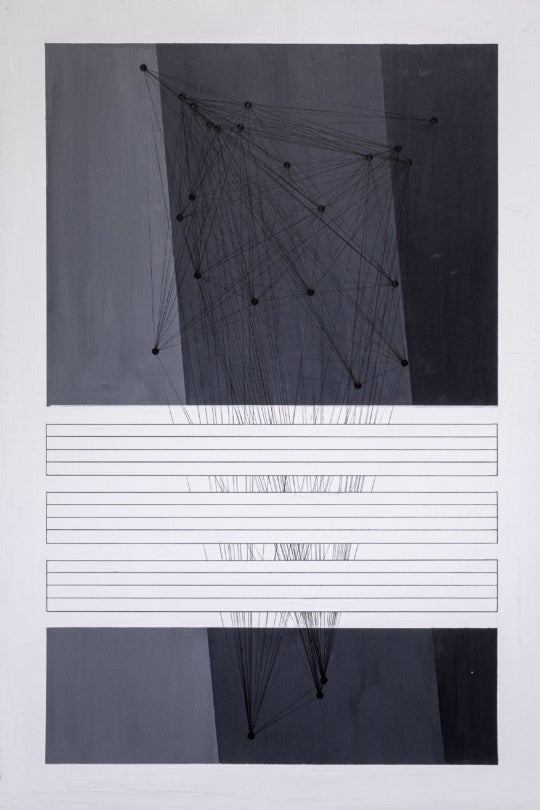

Perhaps Mullen’s works might function better if they were literally and figuratively connected to the works they depicted as part of a conscious critical interrogation. Consider, for instance, Untitled (Art New Yor), Mullen’s remaking of a Pace advertisement. Robert Ryman is represented by Pace, and although the advertisement is not one for Ryman’s work itself, Mullen’s interpretation of the ad is nothing if not a manifestation of the systematic brushstrokes that Ryman so meticulously applied across his canvases. Fortuitous coincidence or theoretical critique spurred by his relentless consumption of art magazines? Who knows?

It may be hard to imagine Mullen not synthesizing the complexities of the artists whose works he views, but it would also be arrogant to believe that he does. Mullen is autistic and unable to communicate verbally; therefore, projecting assumptions onto him and his art can be quite a dubious undertaking.

His creations enliven Basquiat, Carroll Dunham, and others, each one always reconstructed and reinterpreted, or, if you will, reanimated. At times, he reduces his images to their most basic graphic elements, as he does with the head of Tutankhamen. While at other times, his approach to dimensionality and space distills Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge to simply “Marc News” and a gray, nebulous blob.

Inevitably, Mullen’s works exist within a hybrid space. They occupy a space of contemporary discourse, emerging in exhibitions in contemporary project spaces, and engaging with the contemporary art market. Their subjects are predominantly drawn from contemporary popular culture, although the issue of appropriation is one that remains elusive. It would be wise to place Mullen within the lineage of art brut painters, those artists whose works had qualities or characteristics of self-taught expression that eluded traditional definitions. Too often today, the idea of the “folk artist” has been repositioned, while the concept of the “self-taught” artist has been redefined. The former has become more respected, in some ways, while the latter has been moved further to the margins. Mullen is situated precisely where Dubuffet would have imagined: creating radically self-expressive, individual works. They engage with contemporary issues. They respond to a contemporary context. So blame language — but this time, do it for its inability to construct a term that truly defines the type of artist Marlon Mullen is. For now, it can sit comfortably within the context of art brut, but there may be so much more that Mullen’s works could say.

“Marlon Mullen” is at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center through November 7.

Brett Levine is an independent curator, writer, and editor based in Birmingham.