Like Hills Made of Sand by Brayan Enriquez is an exhibition filled with photographs: stark and sweeping compositions that capture a wistful tenderness for a place one has yet to comprehend. This exhibition documents Enriquez’s first trip visiting extended family in Mexico. It is truly a remarkable feat to capture this so pointedly, a complex condition many immigrants and their children face in the United States. It feels like a return home to a place one never knew they were missing.

Upon entering the gallery, it is impossible not to take in the floor to ceiling print, Como cerros hecho de arena (2025) adhered to the wall furthest from sight. The image depicts an elderly woman, sitting on steps with a stoic look on her face that is not uncommon for older generations of Mexicans. If not life-sized in size, it is larger than life in meaning as I imagine the influence she is upon her family. Around her, plants spring forth against concrete walls, out of buckets and various containers. A horseshoe hangs in the corner. All of this contributes to what could be described as a quintessential Mexican home, which Enriquez captures effortlessly. Tile and concrete textures are familiar and ubiquitous to Mexican domestic architecture, giving off the familiarity and placelessness of Mexico’s vastness.

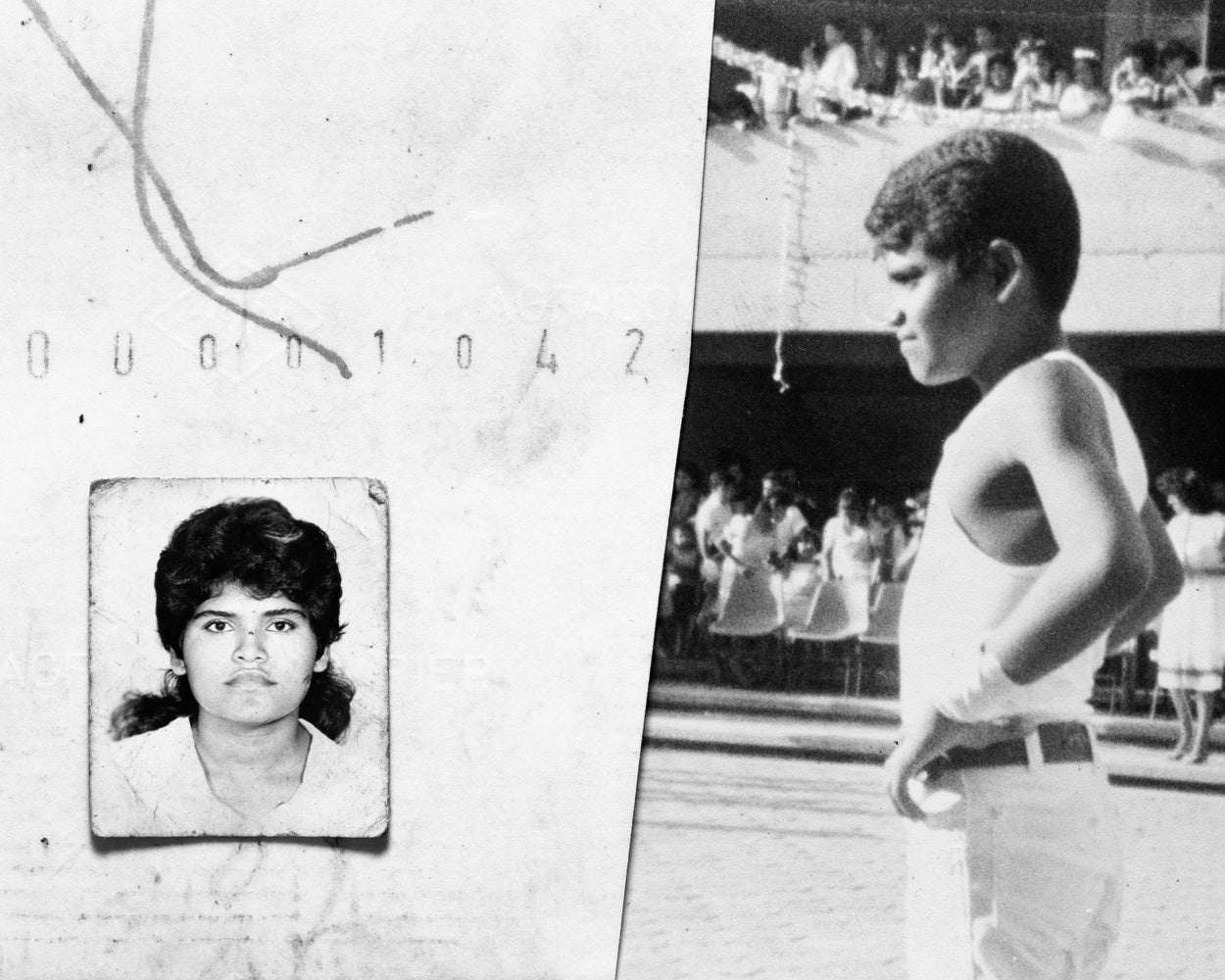

Throughout several pieces involving the archival images, miniature portraits used commonly for official documents are found. I, myself, harbor my own collection of such photographs. Mis tíos y tías existing forever at that age in these miniature photos I keep in a plastic sleeve hidden in my passport. These works seem quiet at first, but further inspection offers a hard reconciliation with a history one tries to hold onto, especially fleeting for those who make the perilous journey crossing borders and leave so much behind.

Drastically different in their image quality, the recent photographs of Enriquez’s extended family can also be read as quiet. Their black and white tones are subtle, almost understated, but they shine in their complex depictions of reconnection with his family that he had not seen until this fateful trip. In several of the images, family members are shown indirectly, from behind, existing as cropped hands, or reflected in the window of a car. Save for Las Primas [2024] where a young girl looks resolutely into the camera, none of the subjects look directly at Enriquez. Contrasting the images Enriquez shot with the miniature archival portraits, the subjects confined to tiny frames are only able to look directly into the camera or are captured in profile. The juxtaposition is striking yet softening in its greater depiction of familial connection.

Personally, I admit a familiarity with Enriquez’s works. They are like a swelling wave, the family rarely seen but welcoming nonetheless. Enriquez delivers an exhibition that is stunning and moving, less of a triumphant homecoming but more so an honest and complicated reunion with one’s own culture and the family that waits back home.