A century of science fiction and disaster films has endowed our society with an expansive visual language with which to make sense of the current moment. Temporary hospitals, empty streets, faceless pedestrians, rapid mass mobilizations— these are all signifiers we know. Last week we watched as New York’s premiere trade show center, the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, was repurposed into a thousand-bed military field hospital. That a venue with a stated mission of being “the marketplace of the world” has been transformed into a government-run emergency healthcare center is a fitting development given our country’s current debate over Medicare for all and the ethics of profiting off the well-being of others. Corporations have begun to put forth clever variations of their own logos, separating graphic elements to emphasize, even if superficially, the dire need for social distancing. As we heed the warnings and retreat from each other, in the name of each other, maybe we can take a very small amount of comfort in the fact that in some dream-like way, this whole situation is familiar to us.

It’s one thing to be able to identify signifiers. Processing the signified—in this case, the spread of a global pandemic and its long-term effects—is a whole different story. We can be grateful, then, that Brandon Ndife has quietly been organizing a lexicon to unpack a narrative of this nature on our behalf. The Louisville-raised, New Jersey-based sculptor currently has an exhibition of new work on view at Bureau, one of the many contemporary art galleries now shuttered to visitors in New York’s Lower East Side. Aptly titled MY ZONE, Ndife’s first solo presentation at the gallery “opened” on March 20, coincidently the same day that Governor Andrew Cuomo ordered the nearly twenty million residents of New York State to stay home to help slow the spread of COVID-19. There was no actual “opening” for Ndife’s show, and like all exhibitions throughout New York City, it is not able to be seen, at least in person, until further notice.

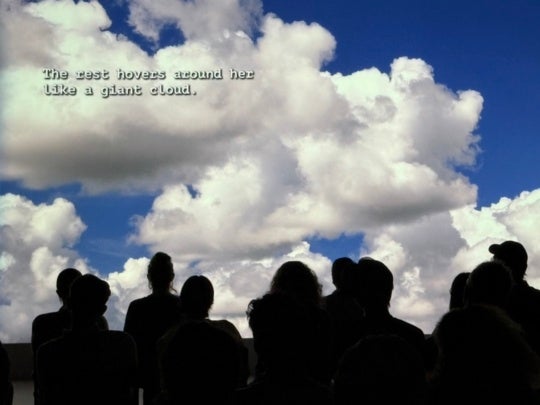

These unfortunate circumstances are ironic given the implied concept of privacy in Ndife’s exhibition title. The two words together are an expression that delineate one’s personal space by describing a relationship between the self and its surroundings in terms of ownership. In this way, the artist makes an unwitting nod to the question of individual liberty that many Americans are likely navigating as they evaluate their “rights” in relationship to the greater public good. The phrase is slightly paradoxical in its rationale, as it stakes personal claim to a category of space that is more commonly attributed to groups—whether governmental, administrative, or psychological, zones are generally not for individuals. Yes, the word zone evokes eerie imagery of isolation, but that isolation is often a shared one. This is especially true at a time when the preservation of one’s own zone is a matter of life or death, for everyone, everywhere. MY ZONE frames an ontological paradox amplified by the crisis at hand, and the words will surely carry an ominous echo as we look back on this period of time and recall the ways in which we each went about maintaining our state and federally recommended six to eight feet of distance from one another.

It is disappointing that the ten beautifully macabre objects that make up Ndife’s exhibition are not able to be seen in person and that no opening reception celebrated the evening their unveiling took place, but these facts are evidence that we are truly in the midst of a global public health emergency. While many galleries, including Bureau, turn to digital platforms for exhibitions that cannot, in their format and aesthetics, fully account for the tone of the current moment, Ndife’s exhibition is oddly harmonious with the disaster at hand. That we cannot yet see and experience it in its entirety enriches the works which are so clearly full of material and spatial play.

Ndife employs a combination of found objects, synthetic and raw natural materials to transform the abusively mundane psychological conditions of life into half-born trophies. Through processes that are mostly invisible to the viewer in the final product, he infuses banal, mass-produced structures with the underbellied psychic karmas of the assembly-line mechanisms which brought them into being. This attention to structure is also present in Ndife’s thoughtful installation, which, similar to each individual object, is its own supplication to the power of form.

At the front of the gallery, separate from the rest of the show, the artist has installed Sconce and Hygge. The objects, which, at first glance, resemble a wall-hanging light and a sideboard table, compound with their location at the entrance of the space to analogize a foyer. Here and throughout the show, multiple concurring dimensions—the actuality of the gallery, the subjectivity of the viewer’s psyche, the fantasy of the objects—are all conjoined into a single aberrated reality. Closer inspection of Sconce reveals a botanic, flower-like formation, more similar to a cotton-blossom than the ornamental bracket for which the object is named. Hygge, like some of the other larger furniture-esque sculptures, is flipped up on its side. Radically simple gestures like this are repeated throughout the show and help to articulate an underlying dream-state logic. Take, for example, Blossoming in Taupe, a wall hanging work which, in its newly evolved state, appears to be a cut-out segment of the gallery’s own floor boards.

At a time when many of us are trapped at home, left with no option but to make conversation with our Ikea dressers, Ndife’s work is a reminder that the lifestyles (and cycles) spawned within the spoils of modernity have always been fraught with an invisible sickness. I am not making—and would never make—the argument that the best way to see visual art is to never actually see it, but somehow that feels acceptable in this case. While I have only seen this show online and through the quiet glass of an empty store front, I can safely assume that seeing Ndife’s MY ZONE in the flesh would better convey the material celebration that the artist intended. There is no substitute for melancholia and its mutations made physical.

Brandon Ndife’s MY ZONE is on view through an online viewing room hosted by Bureau.