As an artist, I credit artists Sam Gilliam and Joe Overstreet as major liberators of and influences upon the development of my creative practice. Presenting works by these formative artists alongside those by contemporary artists working both within and outside of the South—such as New York-based artist Eric N. Mack and Atlanta’s Krista Clark—Unbound at Kennesaw State University Zuckerman Museum of Art forms a vision of abstract art that resonates right now with young Black artists like myself.

Entering the gallery, I am greeted by Sam Gilliam’s Untitled (1970), an unstretched canvas flowing between three points, festooned from one corner to the next and stained with bright fluid acrylic paint, the colors fading in and out of each other in an effect similar to a tie-dyed shirt. Sam Gilliam’s work is displayed one room away from the work of Joe Overstreet. These two artists are the forebears of this unhinged mode of abstraction, pioneering the use of unstretched canvas that Unbound explores. This mode of creating work that rides the line between sculpture and painting has propelled conversations around Blackness forward by creating a new hybrid medium used by many Black artists to develop distinctive forms of abstraction. Eric N. Mack’s Blue Duet I & II is a direct example of this legacy: through the veil of the sheer blue fabric in the piece, I can see the work of Mack’s predecessors, including Romare Bearden, Joe Overstreet, and Sam Gilliam. The way that these works can overlap and interact in the space creates a strong connection between the pioneers of Black abstraction and the generations of young artists who have continued in their wake.

In the back of the gallery, Anthony Akinbola’s large stretched canvas of silk du-rags creates a different disruption of painting, allowing this culturally specific headwear to take the place of brush strokes. For me, this object evokes intense nostalgia: reminding me of my teenage pursuits of having waves and the nightly ritual of brushing my hair, applying wave grease, and putting on a du-rag before bed. Akinbola’s use of the du-rag not only evokes nostalgia and places it in a historical art context, but facilitates a larger conversation around the popularization, demonization, and exploitation of the du-rag.

In an adjacent room, Krista Clark’s Annotations of Sheltered is made up of windowpanes encrusted with insect nests, upcycled two-by-fours, and a tent being held on the wall by a concrete slab—materials clearly sourced from an urban construction landscape. The materials that Akinbola and Clark use in their work move beyond conventional materials for purely formal abstraction; they are also used in the construction of personal identity, foundational to the concept of safety and shelter in the Black communities. Just as the du-rags in Ankibola’s work evoked personal memories for me, the window panes and building materials are a reminder of the fact that I am here on some downtime, in between plumbing jobs, and of the percentage of my plumbing clients that are involved in the process of flipping—buying and remodeling house, often from Black families, with the intent of selling.

As I turn around to spend some time with the works of Tariku Shiferaw, I overhear the voice of a student telling their friends about how much they love the show and can’t wait to have more exhibitions like this. The student had short, well-conditioned hair that left no doubt in my mind that they got a few du-rags at home. As I looked at my distorted reflection in the iridescent, reflective mylar of Shiferaw’s Ivy (Frank Ocean), I considered the excitement and motivation I felt as a student in the presence of artists who not only looked like me but also approach their practice in similar ways. Like Shiferaw, I have also made a work that serves as a visual abstraction of Frank Ocean’s 2016 song Ivy. Titling work after songs by Black musicians and using materials like du-rags, two-by-fours, and tents directly opposes traditional hierarchies of artistic mediums and references. By making the conscious decision to not use such conventional materials—just as Black artists working in generations prior decided to forfeit the confines of the figure or rectilinear canvases—the artists in Unbound provide a nuanced yet accessible form of representation for new kinds of art audiences.

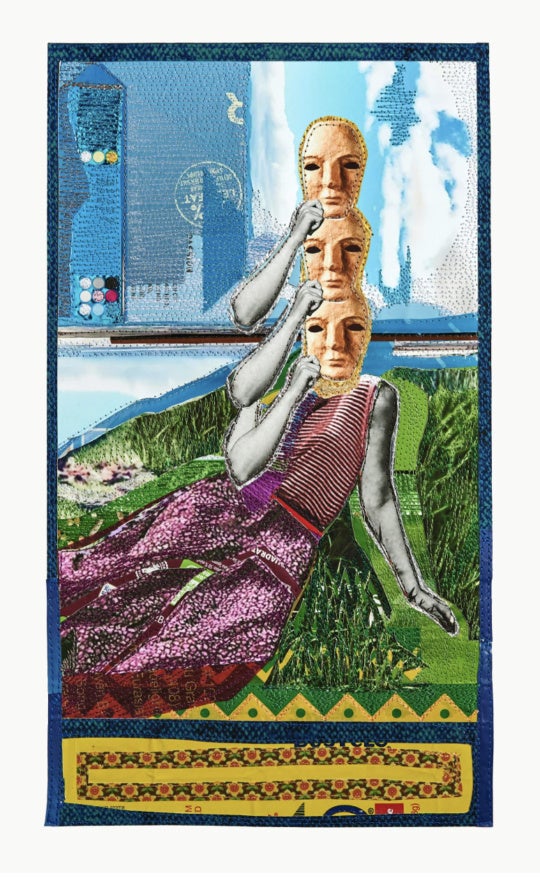

Looming Chaos, a solo exhibition by Zipporah Camille Thompson curated by TK Smith, is presented in another gallery within the museum. As I enter the gallery, it doesn’t take long for me to feel the chaos the exhibition’s title evokes: there are weavings, ceramics, assemblages, installations, all charged with the artist’s presence. The form and scale of the work varies yet all share a rich variety of materials. Barrettes, shells, cassette tapes, synthetic hair, salt lamps, and wasp nest are worked into handwoven tapestries. Enhanced by the rhythmic sound of a loom playing throughout the gallery, the exhibition produces a grounding, meditative space I typically associate with being in nature. The chaos here is not frantic or indecisive but instead has a soothing and healing quality to it. The altar-like works Vasos (vessel) and Varas (wands) recall sites of spiritual or sacred ritual, tapping into ancestral spirits and nature while simultaneously enriched by fantasy and cosmic imagination. The use of synthetic hair, barrettes, and beads takes me back to the mundane rituals of helping my sisters and nieces take their braids out. The meticulous process of weaving and the repetition of materials and form lends Zipporah Camille Thompson’s assemblages a prayer-like quality that feels deeply personal.

While Unbound provides a survey of multiple generations of Black artists working on the margins of abstraction, Loom of Chaos is an all-encompassing view of the work of Zipporah Camille Thompson, a Black woman and contemporary artist working in the intersection of abstraction, assemblage, and collage. One creates a world of linkages between Black artists, the other creates a world of linkages within the mind of one Black artist, and both provide invigorating and resonant visions of the varieties of Black life and experience.

Unbound and Zipporah Camille Thompson: Looming Chaos are on view at the Zuckerman Museum of Art on the campus of Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Georgia, through May 10.