An exhibition at the Georgia Museum of Art in Athens recreates a highly controversial traveling show of modernist American art that was nixed by the government in 1947 following a widespread national protest. As Cold War tensions grew, many of the works were labeled “un-American,” subversive, and unworthy of taxpayer dollars.

Titled “Art Interrupted: Advancing American Art and the Politics of Cultural Diplomacy,” the show includes more than 100 paintings from Advancing American Art, an ambitious project created by the State Department with the intent of using art as an international relations tool. Exhibitions were held in New York, Paris, Czechoslovakia, and Cuba until President Harry Truman essentially pulled the plug.

Modern art is “merely the vaporings of a half-baked lazy people,” Truman wrote to Assistant Secretary of State William Benton. Two days after receiving his letter, the State Department began shutting the project down. The paintings were auctioned off as “war surplus” in 1948.

On view through April 20, the show includes works by Stuart Davis, Jacob Lawrence, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, Robert Motherwell, Philip Guston, Romare Bearden, Max Weber, Robert Gwathmey, Charles Sheeler, John Marin, and other stellar lights as well as works by lesser-known talents. The fated project was designed to show America’s heterogeneity and artistic coming of age.

An award-winning catalogue accompanying the show provides a detailed account of how the project was created and then aborted. It examines the curatorial vision of Joseph LeRoy Davidson, a visual specialist at the State Department, who saw how art could be a weapon in ideological battlegrounds. A symposium on March 28-29, “While Silent, They Speak: Art and Diplomacy,” will addresses the broader theme of cultural diplomacy.

After its 1946 premiere at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the project initially was well-received, garnering favorable reviews in Art News and the Washington Post. But then artists who were excluded from the show began complaining, and criticism mounted in the conservative and mainstream media.

“Letters of complaint streamed in to Washington from all across the country, addressed to congressmen and the Secretary of State. They expressed disdain for the style of art on display, distrust of artists with foreign-sounding names and communistic tendencies, and anger that public money was used to support an unworthy project. Above all, the writers believed that such art was not truly representative of the views and nature of the American people,” explains exhibition curator Dennis Harper, of the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University, in his catalogue essay.

Circus Girl Resting by Japanese-American artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi drew some of the heaviest criticism. The 1925 oil painting depicts a scantily clad, voluptuous woman with a bold gaze, overtly conveying female sexuality.

“If that’s art, then I’m a Hottentot,” Truman declared in a press conference. The portrait looked like Kuniyoshi “had thrown paint on it,” he said.

With such bluster, we can only speculate about why Circus Girl Resting and other paintings displeased the president. But one thing is clear: many of the works do not put a positive face on America.

Social realist Ben Shahn’s The Clinic depicts two women waiting in a corridor lined with the dull green tiles characteristic of old hospitals. Classic maid uniforms convey the women’s socio-economic status. A wall poster with a child’s face asks, “Do I deserve prenatal care?” The commentary remains relevant today.

In William Gropper’s Home, a figure picks through a rubble heap, loosely painted as indiscriminate debris. Born to Eastern European immigrants who labored in New York sweatshops, Gropper used his art to address social injustices. He was targeted by congressmen who questioned the validity of Advancing American Art, and the House Un-American Activities Committee detailed a long list of his “Communist” affiliations, according to the exhibition catalogue.

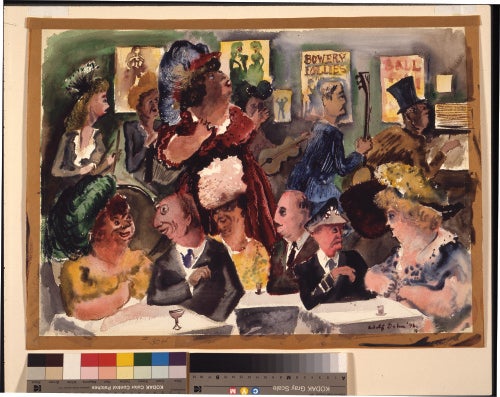

Adolf Dehn’s Bowery Follies depicts a crowded bar not too unlike what we might see in a popular watering hole today. The 15-by-21-inch watercolor is packed with details, almost creating a narrative with cartoonish, grotesque faces. A small-boned man in a military uniform, conversing with a much larger woman, appears dwarfed in the decadent scene.

Only three female artists are represented in the show—Georgia O’Keeffe, Loren MacIver, and Irene Rice Pereira. On loan from the Honolulu Academy of Arts, Pereira’s 1940 abstraction explores space with overlapping geometric shapes—some transparent, some colorful, and some filled with convoluted black-and-white designs.

How Advancing American Art was recreated is a story of its own. In the 1948 auction of the ill-fated works, the museums of the University of Oklahoma, Auburn University, and the University of Georgia were the dominating buyers. From a checklist of 117 oils and watercolors sold at auction, the three institutions collectively hold 85. The Georgia Museum of Art bought its paintings just months before officially opening its doors at the University of Georgia.

Representing a long-held dream of bringing the auctioned works back together, “Art Interrupted” was jointly organized by Georgia Museum of Art, the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art at the University of Oklahoma, and the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University.

The current installation of paintings pairs Osvaldo Louis Guglielmi’s stark tenement buildings with Reginald Marsh’s crush of Coney Island sunbathers. The delightful visual joke adds levity to a show revisiting a censorship that sends chills.

“Art Interrupted: Advancing American Art and the Politics of Cultural Diplomacy” has appeared at the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art, Auburn University, September 8, 2012-January 5, 2013; the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, University of Oklahoma, March 1-June 2, 2013; and the Indiana University Art Museum, September 13-December 15, 2013; and is currently on view at the Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, January 25-April 20, 2014.

Sally Hansell is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta.