“By now, AIDS has become quite well known through scientific publications and the mass media. But its cause is not known. Its method of transmission is not known. And the ultimate measure of its toll in deaths is not known.”

Dr. Walter Dowdle

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1983

That AIDS changed America is indisputable: cultural, visual, and queer studies scholars, as well as medical historians, have been decoding the impact of the AIDS epidemic on American society for decades. With the hindsight of 35 years since CDC published the first notice of what was to be named the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) and with advancements in treatments (not cures) that have made AIDS a chronic rather than fatal disease — at least in the United States — the urgency of the AIDS epidemic has abated. Nonetheless, nearly 700,000 Americans have died of AIDS since 1981, and nearly 1.2 Americans are currently living with HIV (over half of them people of color).

The first known American victims of AIDS were primarily gay, young, white men. They were quickly joined by intravenous drug users, people who received blood transfusions, and a cluster of Haitians living in Miami. Before the virus that caused AIDS was isolated in 1984 and evidence confirmed that it was transmitted through body fluids, this group was known as the four H’s — homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs, and Haitians. They became prime targets for stigmatization and objects of fear — blamed for their alleged bad behaviors or outsider status.

In the early 1980s, identity politics was already agitating American culture when creative communities in all disciplines — visual arts, theater, dance, performance, music, literature, and film — began to be disproportionately impacted by AIDS. Compelled by the urgency of the epidemic, visual artists were early responders. As evidence, there is nary a museum with a contemporary art collection that does not currently have on display at least one major work referencing the AIDS epidemic.

The exhibition “Art AIDS America,” curated by Jonathan David Katz and Rock Hushka for the Tacoma Art Museum in Washington, and now at the Zuckerman Museum of Art, is a “refocused” look at the visual arts response to AIDS from the early 1980s to recent years. The curators have framed the exhibition around a relatively narrow lens of American art history. This defined approach has triggered a controversy, which began in Tacoma, about the lack of inclusion of black artists, to which the institutions hosting the exhibition on its national tour are now responding.

The tragedy of AIDS is the stuff of great art: sorrow, loss, stigma, illness, sex, death, anger, and politics. The main thesis of “Art AIDS America” is that the AIDS epidemic changed American art, with the curators claiming this as the first major museum exhibition to examine what those changes have been. While exhibitions conceived around the artistic response to the disease were organized near the end of AIDS’s first decade, they primarily appeared at alternative spaces and university galleries. Here in Atlanta, in early 1989, Nexus Contemporary Art Center presented one of the first exhibitions in the U.S. that looked at how AIDS was fueling art-making in the groundbreaking “The Subject Is AIDS,” curated by Nexus gallery director and curator Dan Talley and artist Larry Jens Anderson. [Disclosure: I was director of Nexus from 1983 to 1998.]

Anyone versed in the narrative of late 20th-century American art will not be surprised by the work presented in “Art AIDS America”: Robert Mapplethorpe’s photograph of dying flowers; David Wojnarowicz’s image of buffalo falling off a cliff, a recontextualized detail from a natural history museum diorama; an altar by Keith Haring, one of his last works completed before he died of AIDS; a photographic diptych of milk and blood by Andres Serrano; a grid of portraits of dying friends by photographer Nan Goldin. Many well-known artists with recent exhibitions in New York or California are represented: Robert Gober, Catherine Opie, and Martin Wong, to name a few. To bring the exhibition up to current times, recent work by artists such as Deborah Kass, fierce pussy, and Atlanta’s Robert Sherer are included.

Art about AIDS can be categorized into two broad categories: work that looks at the personal tragedy of AIDS and its accompanying losses, and art that is political and/or critiques societal values. The iconography of the former references the detritus of sickness, symbols of death such as coffins and skulls, memento mori, and visualizations of absence and mourning. Lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma (aggressive skin cancer caused by a weakened immune system) that is one of the early sentinel warnings of AIDS is referenced in several works, including Judy Chicago’s 1989 Homosexual Holocaust, Study for Pink Triangle Torture. Tino Rodriguez’s Eternal Lovers of 2010 depicts two flower-embellished skulls kissing.

Photography from the first decade of the epidemic is particularly haunting. Peter Hujar’s 1985 photograph of a ruined, empty bed is just one of several works referencing the absence of life. From the same year, Alon Reininger’s portrait of Ken Meeks, who, marked with Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions, agonizingly gazes at the camera, encapsulates in a single image the personal tragedy of acute illness. A series of intimate Polaroids by Mark Morrisroe documents his process of dying.

AIDS art fueled the culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s with chilling results. The curators look to the work of Cuban-born Felix Gonzalez-Torres as evidence how AIDS activist artists used the legacy of 1970s Minimalism to subversively enter mainstream museums. Completed in 1995, one year before Gonzalez-Torres’s death and installed at the entrance to one of the Zuckerman’s galleries, Untitled (Water) is a curtain made of strands of beads. The collective public and poetic act of walking through the curtain suggests the fluids and medications associated with battling AIDS. Essentially Gonzalez-Torres baits visitors with the language of Minimalism, then switches to a subtle, yet discernible AIDS narrative.

Bridging the personal and political realms of AIDS art is the iconic Rosalind Solomon photograph of a young man — with those tell-all skin lesions — at a 1987 ACT UP rally in Washington, D.C. ACT UP, or the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, was founded in 1987 in New York. This coming together of both gays and straights launched a new type of emboldened activism “united in anger and committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis.” ACT UP and its associated art collective Gran Fury were particularly adept at using visual strategies to criticize both government and the medical establishment. “Art AIDS America” recreates Let the Record Show, the seminal 1987 window installation at the New Museum in New York that juxtaposes in neon ACT UP’s signature logo—a pink triangle over the slogan “Silence=Death,” with damning homophobic statements by an anonymous doctor, Jerry Falwell, and Ronald Reagan.

“Art AIDS America” is truly a landmark exhibition based on an “art historical” narrative defined by a canon of well-known gay, primarily white artists and their friends from New York and California. The Nexus “Subject Is AIDS” catalogue provides evidence that artists across the U.S. were responding to the AIDS epidemic from the 1980s on, most of whom were overlooked in this exhibition. I would contend that Atlanta artists such as King Thackston and Christian Walker did work in the late 1980s worthy of consideration, but that’s the continuing plight of regional artists and another story.

The source of the current controversy is the fact that of the 107 artists included in the original exhibition, only four are African American (the traveling version has been edited because of either space issues or lack of availability for the tour; consequently, some influential artists, including Barbara Kruger and Jim Hodges are not included in the Zuckerman installation). Tacoma-based artist Christopher Jordan led a series of protests against the Tacoma Art Museum about this lack of inclusion based on the fact that 41 percent of people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States today are African American and that AIDS has always been a minority disease. The curators have responded that their focus on art history (meaning the canon) narrows the scope of the exhibition, and that “You’ll have to wait to the next one”[1] for more inclusivity.

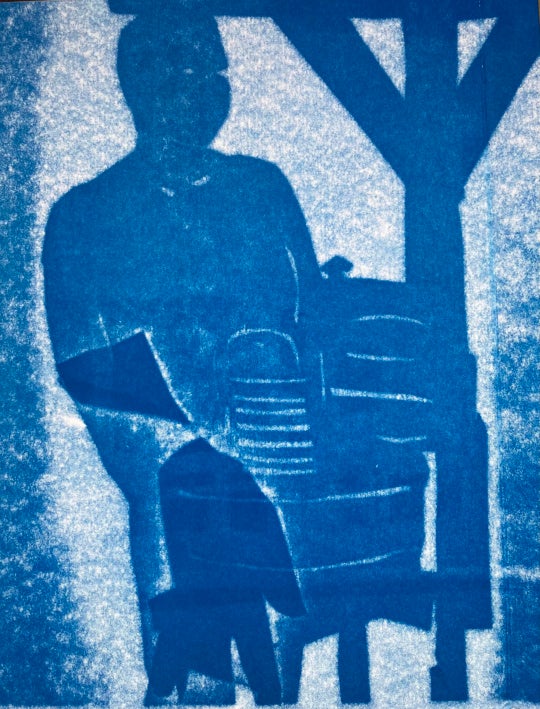

To its credit, the Zuckerman’s curatorial team recognized “the lack of diverse representation” once they received the final exhibition checklist in fall 2015. Working with Atlanta advisors and the Bronx Museum of Art, which is the next venue for the exhibition, the Zuckerman selected new work for inclusion by such well-known black artists as Willie Cole and Marlon Riggs (his landmark Tongues Untied can only be displayed at venues with free admission; the Tacoma Art Museum charges an entrance fee), and regional artists such as self-taught artist Ronald Lockett, who died of AIDS in 1998. Complementing the exhibition is late 1980s and early 1990s archival documentation of AIDS activism in Atlanta, such as flyers and AIDS prevention messages from both the white and African American communities. Portraits of black AIDS activists shot by members of Atlanta’s black women’s photography collective Sistagraphy in 2002 are also included. [Disclosure: I was one of the organizers of this project.]

The Tacoma controversy brings up a larger conversation about the responsibility of curators to dig deeper to challenge the established narrative of any art historical moment — current or past. Clearly, “Art AIDS America” is very personal to the curators, and their selections reflect their tremendous knowledge and engagement. Ultimately, their passion is both the exhibition’s strength and understandable weakness.

Louise E. Shaw is curator at the David J. Sencer CDC Museum at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, and served as Executive Director of Nexus Contemporary Art Center (now the Atlanta Contemporary) from 1983 to 1998.