Afternoon of a Faun is a fascinating new documentary film, screening at Atlanta’s Landmark Cinema May 9-15, about ballet dancer Tanaquil Le Clercq, the dance muse and love interest of two of the 20th century’s great choreographers, George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins. At the height of her career, she was struck with polio, and the film’s gripping story traces the arc to and from the tragedy.

Even in grainy black-and-white footage of dance rehearsals and performances, Le Clercq’s image leaps off the screen: it’s partly the allure of any beautiful and talented dancer, but there’s something more. Though the people around her have appearances in keeping with their times, she—like Amelia Earhart in old footage—looks resolutely contemporary. Though the narrative can feel slow at times, especially towards the beginning when we move back and forth in time, its central tale, of a dancer struck down in her prime, is a gripping one for dance fans and non-dance fans alike. The filmmaker Nancy Buirski’s previous and first documentary film The Loving Story was about Mildred and Richard Loving, the married interracial couple who took their case to the Supreme Court, ultimately overturning laws against interracial marriage.

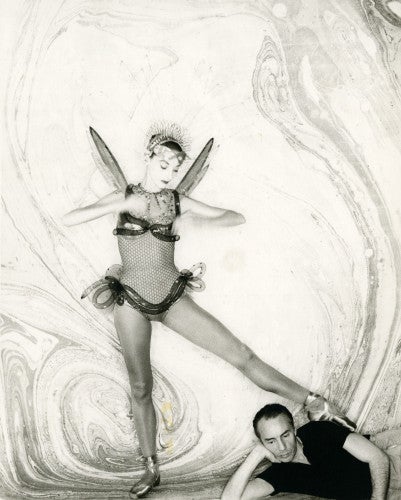

Born in Paris in 1929 and raised in a privileged home in New York, Tanny, as she was called throughout her life, started dancing as a child and was a student at Balanchine’s School of American Ballet when he discovered her. When she was 15 (and already with uncharacteristically long limbs and an elongated body for a ballet dancer), he cast her in lead roles, and she quickly became a star, never actually serving in a corps de ballet and ultimately helping to define the look of a Balanchine dancer.

Dance fans eager for the little bits of gossip and insight about some of the 20th-century dance legends should find a few nibbles here and there: one of the interview subjects informs us that Balanchine liked his dancers to wear perfume, and the dancers would follow his preferences to the point that the smell of all the various perfumes in the studio was overwhelming.

But the film’s larger story is about a philosophical and existential crisis. A couple of the interview subjects use the term “epic tragedy,” and this phrase seems entirely fitting, not just in the sense of “something extremely sad,” but in the sense of a drama on universal themes played out in the most heightened and condensed form. Every dancer, every human being, will become diminished, no longer able to move or live.

As the dancers of the City Ballet were preparing for a tour of Europe in 1956, all were being vaccinated before the trip: Le Clercq decided to skip her turn and get the vaccine when she came back. She contracted polio on the tour: one night she was dancing in Copenhagen complaining of stiffness, the next she was in an iron lung. She never walked or danced again.

The sequence of events doesn’t just seem tragic or unjust; it seems existentially insulting. Le Clercq in letters remains calm and plain-spoken: she had a grim sense of humor that served her well when circumstances turned genuinely dire. But clearly running underneath her cheerfully naughty jokes about the body odor of her nurses or her enjoyment of a screening of 12 Angry Men at her convalescent center in Warm Springs, Georgia, is a terrible howl back at the universe. Her letters often turn lyrical, pensive, as she skirts around the question “why,” knowing there is no answer.

Her loss of identity is an open and shut question: she is a dancer who will never again dance, so she grows in other ways and becomes a teacher much as other great dancers would do. Her relationships with Balanchine and Robbins get complicated, dramas that take you through the latter part of the documentary. Le Clercq lived to the age of 71 (she outlived Balanchine, who had divorced her and married someone else, by more than 15 years). She herself in a recorded interview believed there was a terrible irony in the career of even healthy dancers: at the very moment a dancer attains great mastery of the art, the body is past its prime. She continued to live alone for her last 25 years, we’re told, and those around her imply in interviews that her survival, her continued enjoyment of life, was an act of embittered defiance. A great documentary always touches on the mystery of human personality, and Afternoon of a Faun spotlights a truly intriguing one.