Howard’s and Tif Sigfrids galleries: are they two? One? Step through one doorway and you’re in Katya Tepper’s untitled mixed-media installation at Howard’s. Step through another and you’re in Adrianne Rubenstein’s painting exhibition, Little Shop of Horrors, at Tif Sigfrids. At times, the two galleries swap spaces. Both galleries—light-filled, rectangular rooms on the top floor of a Federalist-style building in downtown Athens—are small enough to quickly walk through one, move to the next, return to the first, repeat.

The works in Tepper’s exhibition might be described as ambiguous three-dimensional images. In a state of perpetual vacillation, Tepper’s constructions do not waver between distinct forms like rabbit–ducks or Rubin’s vases. Instead, they oscillate between two genera of matter: the organic and the inorganic.

The most captivating work in the show, My Life as an Inside Down Carrot, is a heap of fabric scraps, plunger heads, eggshells, rubber tubing, tree branches, polyurethane foam, soil, and carrots. It lies squarely in the tradition of “trash art” or poubellisme pioneered by the French-born artist Arman and his midcentury contemporaries. But where trash art tends to resolutely deny the organic by presenting a striking assemblage of manmade waste—plastic bottles, aluminum cans, Styrofoam—My Life juxtaposes the bodily, the organic, the decaying with the synthetic, the chemical, the veritably eternal.

Juxtapose may be inaccurate, however, since Tepper’s work is never organic and inorganic at the same time but rather in alternation. From one perspective, My Life seems a massive, exposed bodily organ: the foam sealant attached to eggshells gives the impression of running yolk; the rubber hose coiled on the floor evokes an intestine; the scraps of flesh-toned fabric suggest dissembled skin. As in Paul McCarthy’s Painter (1995; TW: violence, self-harm), Tepper’s assemblages seem to transubstantiate manufactured products like plastic or paint into biological materials. The transformation works both ways, however. The polyurethane “yolk” gives off a strange synthetic shimmer, the tree branches link back to their plastic painter’s bucket base. The brilliant red stain on a piece of rope no longer looks like blood, but marker or acrylic. Objects that previously appeared to constitute an enormous organ now look like parts from a disassembled machine.

The distinction between the natural and artificial has always been tenuous. But speaking roughly, Tepper’s work is, in turns, a representation of the natural being rendered artificial and the artificial being assimilated to the natural. The triumph of the former process is foretold in our present: a future planet completely covered in plastic, metal, and glass, rather than roots, foliage, and organic waste. By giving shape to both processes in a single show, Tepper acknowledges our unavoidable complicity in the planet’s overwhelming saturation with inorganic, undecaying, mass-produced shit.

Ambiguous images are also at work in Rubenstein’s Little Shop of Horrors. Here, these images pose a question of natural forms versus the human figure, the realm of natural objects versus that of manmade objects, or simply human scale versus insect scale. Hammer and Nail faithfully depicts its titular subjects in bold, satisfyingly thick strokes of paint.. Yet it is equally legible as a warped landscape seen from an aerial perspective—a depiction of household tools becomes a topographical view of fields or bodies of water.

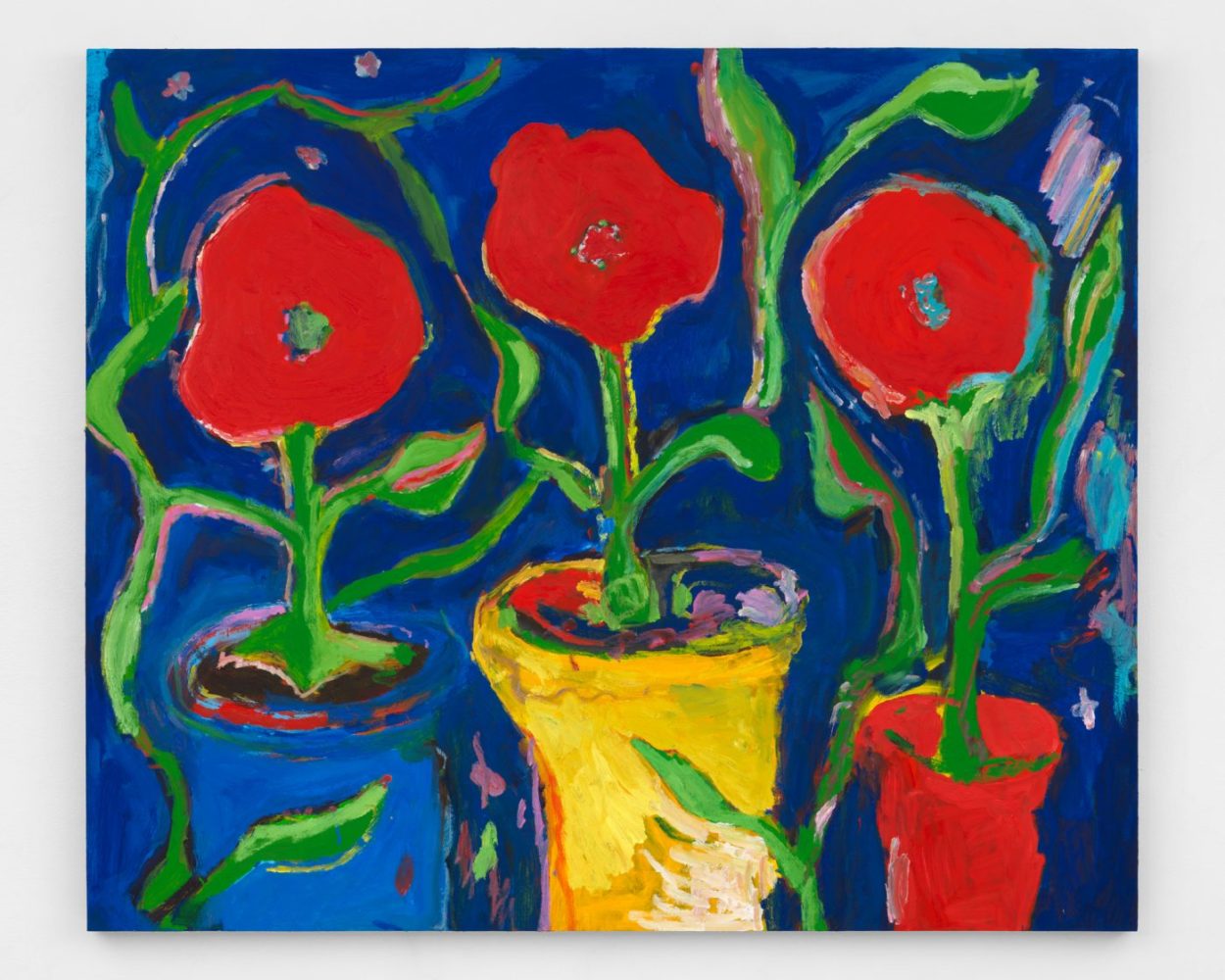

Rubenstein’s Audrey 1, 2, and 3 generates a similar sense of double vision as Hammer, not through ambiguous spatial perspective but through personification. While the three flowers represented in Audrey can stand as idiosyncratic depictions of a common still-life subject, the cartoonish visual language in which they are rendered—sparse shadows, primary colors, front-facing flower petals—gives the impression that their stems are arms waving in the wind, their petals are heads.

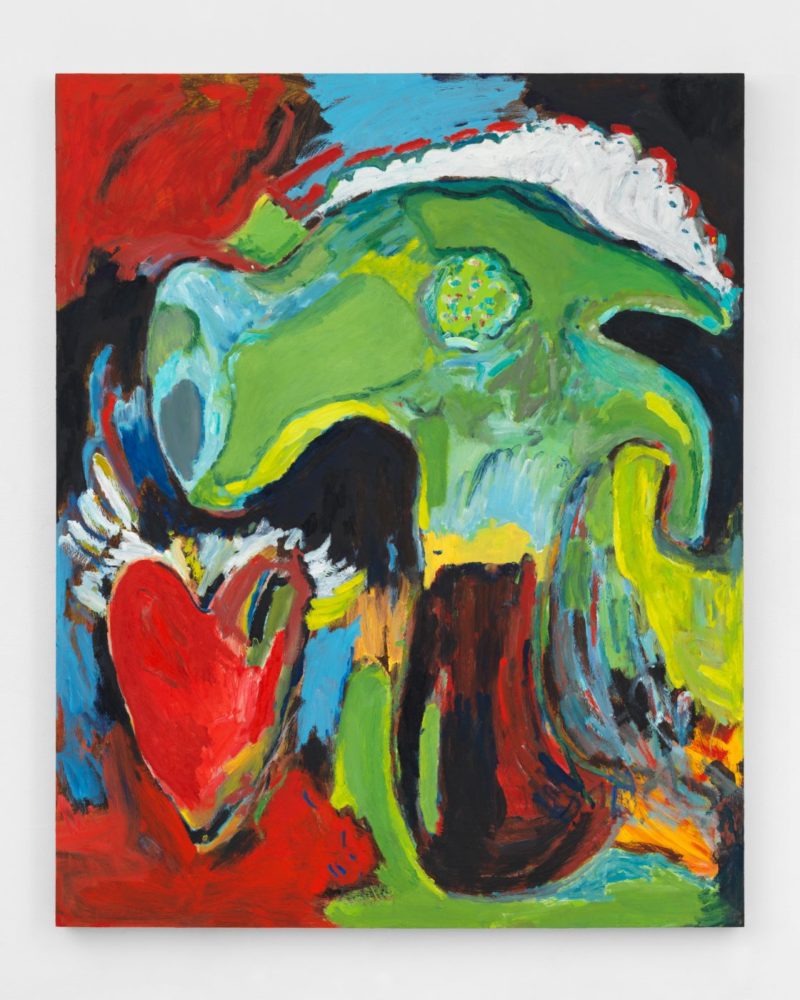

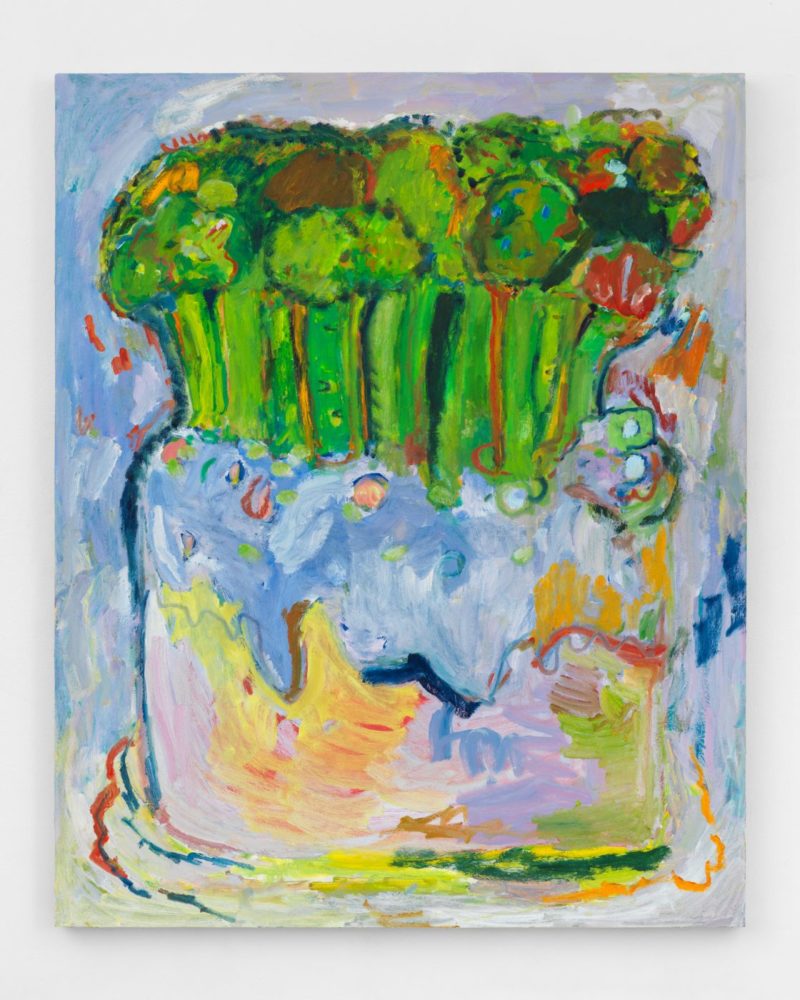

In Amorous Bees, two bees are endearingly anthropomorphized through the simple trick of enlargement: their faces are painted at roughly human scale. This gesture is vaguely akin to that found in Broccoli Birthday Cake, wherein pieces of broccoli seem less like small vegetables than tall trees in a dense, verdant forest. Rubenstein’s works imagine what the world looks like from the eyes of an ant with the mind of a child.

But all these thematic notions may be secondary to the simple matter of color. Rubenstein is willful in her use of certain tones, or colors her subjects as if they were filtered through the beautifying lens of remembrance. She seems to compel her forms to contain the colors that most appeal to her and, as a result, her paintings are dazzling and vibrant, paintings your eyes can sink into. Her wide brushstrokes and minimal shadows often encourage attention to pure color over objective form. This tendency finds it strongest expression in Vanilla, which looks like it was made by combining every color in every Helen Frankenthaler painting within a single surface area—not in translucent watercolors, but thick, undiluted lines of oil paint.

In Howard’s, standing before Tepper’s installations, nature at times seems capable of dominating the manmade. In Tif Sigrids, standing before Rubenstein’s paintings, nature seems beautiful and integrated with the human, or, the human seems beautiful and natural. Both exhibitions present an inviting alternative to what today seems—and very likely is—a doomed opposition between the two.

Solo exhibitions by Katya Tepper and Adrianne Rubenstein were on view at Howard’s and Tif Sigfrids in Athens, Georgia, from September 15 through October 19.