What we at first find ordinary can become fascinating if we choose to turn our minds a certain way. This is the driving idea behind the retrospective of Abelardo Morell’s photographs, “The Universe Next Door,” at the High Museum of Art through May 18.

For the last 25 years, since about the time of the birth of his first child, Morell has explored his domestic world in detail (Laura and Brady in the Shadow of Our House, 1994). His experience of teaching at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design seems to have had an effect similar to his becoming a father, as his pedagogical mission brought his focus to the elements of photography—the basic principles of the camera, of light and optics, and of staging that play with light and form (Light Bulb, 1991).

Morell, who won the International Center of Photography’s Infinity Prize in 2011, says that it was his work teaching students pre-photographic techniques that led him to begin using the camera obscura, a darkened enclosure or room with a small opening through which light enters and projects an upside-down image of the external environment. These camera obscura images, which he captures on film, have been central to his work since the 1990s.

The High Museum’s retrospective, organized by the Art Institute of Chicago in association with the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and the High, comprises 125 prints, including 15 that were commissioned for the High’s “Picturing the South” series. The exhibition is divided into Morell’s areas of interest: the camera obscura; explorations in light, motion, and dark room techniques; photographing books and other objects made of paper; images of art museum interiors; and recent work pertaining to the Southern landscape.

Wall text in the exhibition states that Morell’s works “employ the language of photography to explore visual surprise.” His curious nature is plain to see in many pictures, such as Motion Study of Hammer Impressions on Lead (2004), and Still Life with Wine Glass: Photogram on 20 x 24 Film (2006). For the former, inspired by Eadweard Muybridge’s motion studies, Morell made three consecutive reliefs of a hammer on a single sheet of lead and photographed it, giving the impression of it descending on a nail. Still Life is a photogram, made with light and film but no camera, depicting glass objects in a three-dimensional space. Morell plays like a child who will take an old picture, figure out its guts, and rearrange them for his own invention.

Morell’s photos of books, some of which he made during a term in the mid-1990s as artist-in-residence at the Boston Atheneum, frequently take a playful approach to their subject. Morell has said that he is drawn to books as tactile objects that have stories to tell apart from their authors’ texts. In Two Books of Astronomy (1996), he places two volumes together: one is opened to a picture of an astronomer looking through a telescope; the other, set just beyond that telescope, reveals a picture of a dark cosmos filled with stars and galaxies. Morell’s image evokes the mental enterprise of using two-dimensional planes to explore a multi-dimensional reality.

All of this play might make it possible to find rich psychological content in Morell’s pictures. When the imagination is let loose, the content of dreams becomes apparent. The surreal nature of Morell’s camera obscura photos is frequently mentioned, as they employ a layering of two disparate images. For example, an image of a monumental structure, such as the Brooklyn Bridge, is projected over the interior of a bedroom. The juxtaposition evokes dreams and the presence of clashing realities. Most of Morell’s photos, whether or not from the camera obscura, contain a juxtaposition that generates an intimation of time and transformation, transcending the stillness of photography’s inclination toward “moments.”

In the 2007 documentary film about Morell, The Shadow of the House (not in the exhibition), the artist says, “If I were a critic and was looking at my work, I would say there’s a lot of horror in it, too, there’s a darkness, and suffering, and decadence, and decay.” The camera obscura piece titled Manhattan View Looking South in Large Room shows the faded gray, geometrical clutter of city buildings projected upside-down into a room occupied only by an empty table and a stray chair. This image is a surreal dramatization of the darkness of hyper-urban busy-ness.

Yet pieces similar to Manhattan View lack depth and can feel devoid of the darker emotions of dreams. These include images of the Brooklyn Bridge projected into a bedroom; the Manhattan Bridge projected into a nondescript room; Venice’s Piazzetta San Marco; Venice’s Santa Maria della Salute; and yes, a view of midtown Atlanta projected into a conference room. The artist’s oeuvre also includes camera obscura pictures of the Eiffel Tower, Rome’s Pantheon, and Venice’s Grand Canal. One could suspect that Morell had taken his special camera technique on the “grand tour” with negligible psychological discovery or social observation.

Leaving aside the technique of camera obscura, other photographers have explored the layering of images and hit upon comparatively emotional and disturbing works. Robert Heinecken (1931-2006) and Heinz Hajek-Halke (1898-1983) shared Morell’s delight in exploring the elements of photography. Both older photographers’ works manipulated images of people, whereas Morell’s techniques frequently require very long exposures for which human subjects are unsuitable. Consequently, Morell’s work, by contrast, looks driven by mechanics.

Although Morell has said that he has no interest in producing documentary photography (though in his early career he emulated the work of Cartier-Bresson, Frank, and Arbus), the fact remains that he aims to use photography to express his view of reality, to investigate what has been obscured by ordinariness. This would seem directly related to Morell’s life experience of fleeing Cuba with his family at the age of 14, during the early stages of the Cuban revolution, resulting in a formative exile.

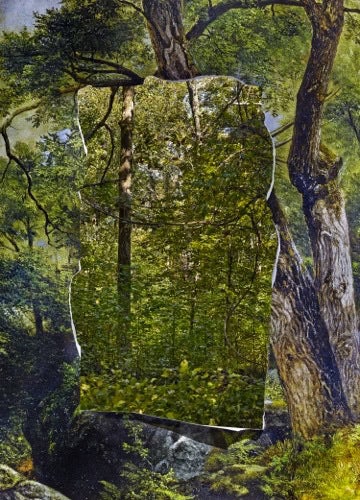

Morell’s “Picturing the South” photos include cameras obscura of Atlanta scenery, such as the trees outside Lucinda Bunnen’s bedroom projected into the room, and newer work in color. In Cutout in Print with Trees Behind (2013), a painted picture of trees has a hole in its center that reveals the real trees behind it. Several photos like this challenge the viewer to touch the magical innards of images while considering how pictures affect our perceptions.

In “The Universe Next Door,” the elements of clashing imagery, contemporary dream life, and the effects of camera technology on perception are all at play. There’s far more to be found in Morell’s work than fleeting fascination.

An exhibition of Abelardo Morell’s “Tent Camera Obscura” series can be seen at Jackson Fine Art through May 3.

Bryan K. Alexander is a writer who lives in Atlanta and publishes AtlantaArtBlog.com.