Courtesy of The Mildred Thompson Estate and Galerie Lelong & Co.

Approximately one year after her death in 2015, Beverly Buchanan’s largest solo exhibition opened at the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. Organized by artist Park MacArthur and curator Jennifer Burris, Ruins and Rituals was curated by and presented in a space named for white women. Buchanan, who was Black, spent the majority of her career in Macon, Georgia, making work about Southern vernacular architecture and receiving important, if scant, accolades, including a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1980 and an Anonymous Was A Woman Award in 2002. Buchanan had been celebrated in her home state as well: her work was acquired by the High Museum of Art in 1982, and the public sculpture for which the name Ruins and Rituals comes has been installed prominently at the Macon Museum of Arts and Sciences since the artist gifted it in 1979. Her recent arrival into feminist and twentieth-century canons of art, however, has largely been brokered by the Brooklyn Museum survey and the exhibitions and acquisitions that followed in its wake.

This story represents a recent phenomenon in museums across the country: the re-emergence of important Southern Black women artists through the efforts of women curators, many of whom are white. As a sometimes-curator and artist living in Atlanta, I’ve been curious about the ethics of curating artists of color as a white woman, of embodying a new wave of feminism that does not fall into the same pitfalls of “white feminism” which have so often ignored, disrespected, and further alienated Black women from the ongoing battle for greater equality and art world investment. How might white women promote, steward, and champion the work of artists of color while also making space on the bench for peers of color in institutions that are clamoring—if not fast enough—to achieve more “inclusivity?” Similarly to Buchanan’s survey, there are several recent examples that begin to untangle and explicate the work that is and needs to be done.

The exhibition that immediately followed Ruins and Rituals in the Sackler Center at the Brooklyn Museum was the landmark survey We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965—85, which defined, for the first time in a large-scale exhibition and catalogue, a Black feminist aesthetic of the late twentieth century. Organized by Sackler Center senior curator Catherine Morris and 2019 Whitney Biennial curator Rujeko Hockley—who then worked at the Brooklyn Museum—the exhibition reintroduced many artists who had not been visible in museums for decades. It did not, however, include several of Buchanan’s Southern neighbors who have instead been the subject of recent and forthcoming solo exhibitions in Southern museums: Mildred Thompson, Suzanne Jackson, and Mavis Pusey. Much like Ruins and Rituals, the three museum exhibitions focused on these artists are spearheaded by young white women curators and scholars.

These curators’ fascination with heretofore under-exhibited Black women artists from the South comes in the wake of recent call-outs and calls-to-action by a wave of outspoken artists, critics, and curators of color who have been fighting for a more inclusive picture of American art for decades. Valerie Cassel Oliver, Naomi Beckwith, Aruna D’Souza, Lauren Haynes, Hannah Black, Kellie Jones, Saidiya Hartman, Andrea Barnwell Brownlee, and Thelma Golden, among many others, have led some of the most astute and meaningful efforts towards this end. The white supremacy of the art world has necessitated that women of color spend their careers agitating for change and performing the emotional and intellectual labor to demonstrate how to better make space for non-white artists. And after years of scholarship, exhibition making, and sharp criticisms of an endless stream of corrupt or obtuse art world behavior, these thinkers have moved the dial on how we look at the machinations of the art world and the ideologies of exclusion that buttress it.

In the last year, white women at Southern museums have taken on major solo exhibitions and advocacy for Black women whose contributions to late twentieth-century American art have been institutionally under-acknowledged. These include the New Orleans Museum of Art’s recent presentation of Mildred Thompson’s works curated by Melissa Messina and Katie Pfohl, the Telfair Museum’s current retrospective of Suzanne Jackson’s career by Rachel Reese, and the forthcoming survey of works by the late Mavis Pusey at the Birmingham Museum of Art by Hallie Ringle. While neither these curators nor these artists are monolithic, and the circumstances of each working relationship are unique, I’m struck by the trend represented by these exhibitions happening in close succession. Is this a meaningful attempt to create a new intersectional, intergenerational form of advocacy and visibility for femme artists and curators in institutions all too quick to ignore diversity when it’s unpopular and capitalize on it when it’s in vogue? Is it virtue signaling, base covering, turf grabbing? I believe it’s possible for these collaborations to be both well-intentioned and revolutionary while fraught at the same time.

Florida-native Mildred Thompson was a writer, educator, and highly accomplished abstractionist who spent most of her early life moving around to pursue an art education and find refuge from the racism of the South. Her time in Germany and the resulting wood assemblages she produced during that period were the subject of a late 2018 solo exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art co-curated by the museum’s in-house contemporary curator, Katie Pfohl, and the curator of the Mildred Thompson estate, Melissa Messina. A former student of the artist, Messina has been a major force in championing and stewarding Thompson’s work and legacy, curating her into institutional surveys and other solo presentations including the current exhibition at Atlanta’s Spelman College Museum of Fine Art. The exhibition at Spelman represents a homecoming of sorts for Thompson, who, in addition to being an active artist in the Atlanta scene in the 1980s and 90s, was also a professor at the Atlanta College of Art and associate editor of Art Papers magazine during this active period of her later life. Despite these recent institutional solo presentations, Messina reminded me in correspondence that Thompson has yet to receive a full career survey.

Museum of Art and Mavis Pusey Archive

This notion of the curator as steward is also demonstrated in the curator-artist relationship between Hallie Ringle of the Birmingham Museum of Art and Mavis Pusey, the recently deceased Virginia-based abstract painter. Pusey was famously one of the very few women included in the seminal yet problematic 1971 Whitney survey exhibition, Contemporary Black Artists in America (which was ham-handedly curated exclusively by a white man). When I first met Ringle in spring of 2019, she buzzed with excitement about her work and research with Pusey, encouraging me to visit her home and studio if I was able to. When Pusey died in April—though not unexpectedly, at the age of 93—Ringle sent along a beautifully penned obituary which became the basis of the coverage of Pusey’s death by Burnaway, Artforum, The New York Times, and The Studio Museum in Harlem. Though currently in the works, Ringle’s forthcoming exhibition of Pusey’s work has already been awarded a prestigious Andy Warhol Foundation curatorial research grant and, bolstered by the curiosity wrought by the artist’s recent passing, is sure to receive a level of attention and visibility rarely afforded to a solo exhibition originating in a Southern museum.

Curated by Rachel Reese, artist Suzanne Jackson’s 2019 retrospective at Savannah’s Telfair Museum represents a rare instance of a living artist working closely with a curator to produce a career-defining presentation. Accompanied by a significant catalog and recent presentations in both New York and Los Angeles-based galleries, Jackson’s exhibition feels like the sort of carefully planned, fog-horned, grand celebration that many of these artists deserve. When I first visited Jackson and Reese in Savannah in April of this year, they were in Jackson’s cleaned-out studio (her work had been transferred to the bowels of the museum three miles away), excitedly discussing which ephemera to include in the exhibition. Visiting five months later toward the tail-end of the show’s run, when I asked Jackson how she felt about the exhibition and the surge in her visibility, she expressed to me not the sort of gracious aloofness I expected, but a commanding proclamation that of course this is how things were unfolding. It was, after all, how she engineered things to be, and it was about damn time the rest of the world caught up. Trained at Yale in theater design, Jackson’s strong proclivity for staging a moment was a welcomed gesture of confidence and self-determination.

I am also implicated in this trend. In 2016, while my husband and I ran an alternative art space and curatorial project called Species, we presented the work of Bessie Harvey, a deceased so-called “self taught” sculptor from Tennessee, in a hip Lower East Side gallery summer show. Later, in 2017, while I worked as a curatorial assistant at the High Museum of Art, my first solo curatorial endeavor was an exhibition examining Civil Rights photography and the legacy of 1968 that largely focused on the work of Dr. Doris Derby, one of the few Black women who worked as a staff photographer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. My work with Dr. Derby extended well beyond the scope of the exhibition’s gallery walls (and my relationships with other artists in the show) eventually involving a major public program and a large print profile in Art Papers magazine. At the time, I flattered myself by considering this as a gesture of mic-passing and proactive intersectionality, but this position now feels complicated. It was me, after all, getting the paycheck from the High Museum, the check from Art Papers for the published article, and the lines on my CV that have propelled me into the position of director of an arts publication. My own enthusiasm for and advocacy of Black women artists was genuine, but it has also been self-propelling in ways that don’t always feel right, that give me pause.

Could this seed-sowing of doubt be more of the self-sabotage that stymies the rise of feminist leadership in the ranks of museums and prevents women from confidently occupying their potential to make space for Black, indigenous, queer, disabled, and femme artists in the canon? Perhaps. But now feels like the time to take stock of the power balance in the artist-curator relationship, especially when the artists in question often don’t have the power of white-gloved mega-galleries managing their estates and are sometimes not alive to weigh in on who curates their retrospectives and speaks on their behalf in catalogue essays.

Contemporaneously, many women curators and art historians are still waiting for the reins in museums dominated by male leadership, often unknowingly working for less pay than their male peers. One of the only satisfying bucks-to-the-system that a female curator may eke out during the first decade or two of her career may be the minute power and gratification afforded her by not using her role to further drive the same old bad boys and thin white feminists deeper into the trenches of the American canon. At the end of the day, there’s everything right about Black women artists who have spent the better parts of their lives making do with what the art world has grudgingly bestowed finally receiving career-defining and history-making solo presentations of their work, in Southern and non-Southern museums alike. While the potential for stepping on an ethical landmine might worry some white curators away from engaging directly with questions of race and representation in the museum, the work of repairing the canon to not only represent a diversity of race and gender but also a diversity of regions and economic backgrounds (among countless other identifiers) remains critical to building a more true and complete American art history, and this task can’t be the sole responsibility of the very few curators of color in the field.

Despite the lack of Southern artists in We Wanted a Revolution (and other recent survey exhibitions emphasizing Black identity) the majority of the Black population in the United States currently resides in the Southeast, with more Black Americans moving away from the Northeastern and Midwestern industrial destinations of the Great Migration to return to a more reformed (if still violent and racist) South [1]. Despite rapid gentrification, Black women are the single largest demographic represented in the metro Atlanta area, and yet Atlanta’s High Museum—which has recently received national attention for its attempts to bring greater diversity to the exhibition program, permanent collection, and museum visitors—has not organized a major solo exhibition of a Black woman artist (much less one from the South) under the banner of canonical contemporary American art in over twenty-five years [2]. The first such presentation will happen in 2020 when the museum will host a traveling survey of the art of Julie Mehretu organized by two curators of color from the Whitney and LACMA (including the aforementioned Hockley).

Photograph by David J. Kaminsky.

© Suzanne Jackson.

Perhaps I’m simply trend-casting the white femme guilt of millennial and proto-millennial curators coming into their own in Southern museums, or highlighting the possibility that, since curators of color and Northern institutions have paved the way, museums and curators in the South have given themselves permission to finally embrace the artists who have always been there. But what I hope this moment indicates is the rise of a new generation of feminist curators willing to stick their necks out for women artists of color, despite the risk that call-outs may follow and exhibitions may not get the national press attention they deserve, that careers might stall without the lubrication provided by appealing to the rosters and collectors of New York mega-dealers. I also hope that the curatorial interest in women of color who have been long overlooked will embolden white curatorial staff members to demand greater diversity in their own ranks—even if it means foregoing the friendly, nepotistic tendencies of the field—and actively recruit aspiring curators of color, a gesture that requires respecting the needs and calls for change that an upcoming generation will undoubtedly bring to institutions.

Museums are direct descendants of colonial and patriarchal European aristocracy, evolving from sixteenth-century cabinets of curiosity which publicized spoils from distant lands into public collections named for their wealthy founders [3]. While some institutions have gone to great lengths to correct centuries of violence and classism by repatriating artifacts, changing language in permanent collection galleries wall labels, and aspiring to greater diversity of artists, many still operate as hierarchies with men at the top and white women at their heels, often mimicking their leadership styles. In order for any curator to adequately present the work of diverse artists, norms of academic and institutional expectations—for example, the immense cost barrier to the education required for such positions—need to be examined as much as outward facing curatorial appointments, acquisitions, and exhibitions. What would a more egalitarian and diverse internal culture look like within large institutions, and why shouldn’t this be as much a priority as correcting the patriarchal white supremacy that has for generations defined the outward presentations of the work museums do through collections and exhibitions?

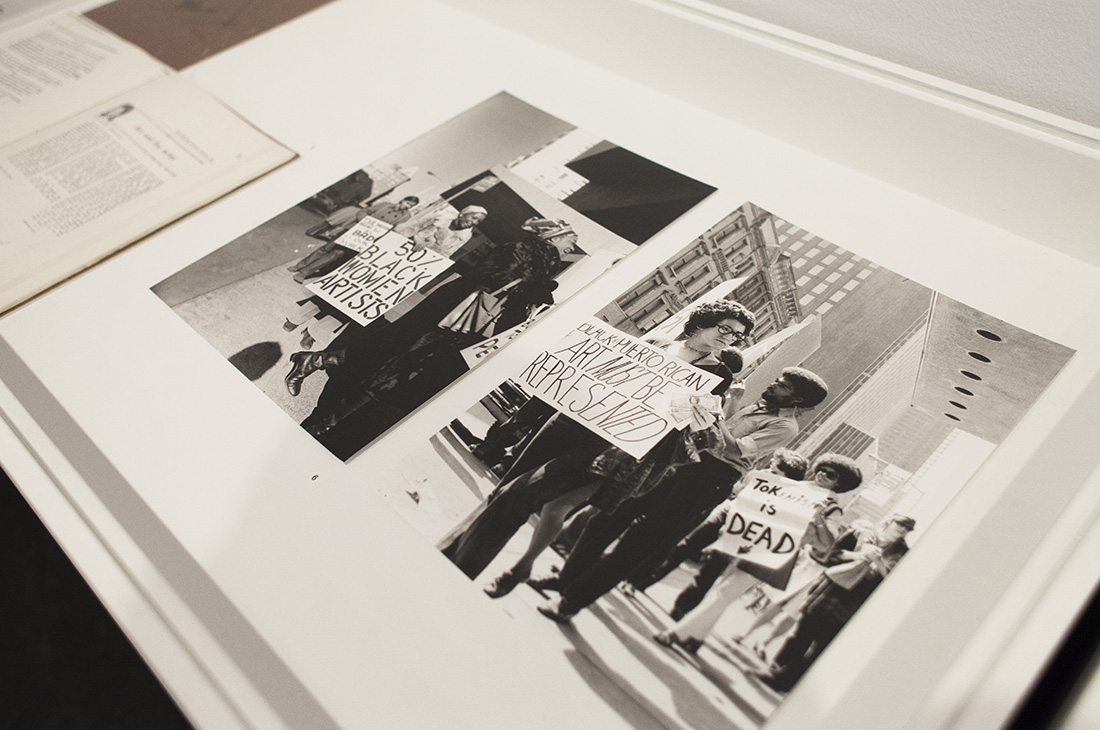

No one is more aware of this ecosystem than Howardena Pindell, who, at a conference at Hunter College in 1987, delivered a prepared testimony addressing the dynamics between cultural institutions, white women, and artists of color. Pindell’s “Art (World) & Racism: Statistics, Testimony and Supporting Documents” appeared in the desert of the post-Black Art and post-Women’s Lib movements, demonstrating how little impact these decades of action seemed to have had on the art world. Having withstood over a decade of microaggressions as an associate curator at the Museum of Modern Art while also maintaining an artistic career, Pindell was uniquely equipped to speak to the relationship between markets, labor, class, and institutions. In her testimony—which was later reprinted in the catalogue accompanying We Wanted A Revolution—Pindell said, “Over fifty percent of the citizens of New York are people of color… More than two-thirds of the world’s citizens are people of color. I am an artist. I am not a so-called ‘minority,’ ‘new,’ or ‘emerging’ or ‘a new audience.’” While nothing short of scathing and bleakly factual, her testimony was the queasy, squirm-inducing confrontation that the art world needs in this moment, complete with that punch-in-the-gut feeling that results from realizing how white supremacy has shaped even (and especially) the most progressive sectors of American culture.

Black women in the South are by no means a minority today, nor are they a new, emerging audience. Yet the makeup of museums’ curatorial staffs and subjects of upcoming exhibitions sometimes suggest otherwise. This is also true more broadly across the United States. A much-discussed report published by artnet News in September 2019 stated that, between 2008 and 2018, “only eleven percent of art acquired by the country’s top museums for their permanent collections was by women,” with only three percent (190 of 5,900 artists) by African American women. When the stated goal of the twenty-first century museum is to build the most complete and interesting version of American art history possible, attempts at reform must go beyond anachronistic and short-sighted gestures toward inclusion and diversity: tokenistic and temporary solutions that merely mask persistent structural inequities. Any significant advances toward an intersectional, intergenerational form of advocacy for marginalized femme and queer artists requires not only posthumous and late-career surveys—as deserved as they may be—but also the incorporation of those perspectives at all strata and career levels of the art world. My hope is that, after decades of proving otherwise, white women curators, art critics, historians, and administrators can begin to respond to Toni Morrison’s 1971 claim that “Black women have no abiding admiration of white women as competent, complete people” [4] and perform the transformative emotional and intellectual labor to champion artists of color not only as subjects but as venerable thinkers, curators, peers, and leaders in their own right.

[1] A trend reported in the 2010 census.

[2] The High has presented solo exhibitions of Black women artists within its African Art, Self-Taught Art, and Photography departments, but never from the Contemporary or American Art Curatorial departments.

[3] Tate, Whitney, Getty, Guggenheim, Frick, High, and so on.

[4] Toni Morrison, “What the Black Woman Thinks about Women’s Lib,” (The New York Times, August 22, 1971).