“Not only will I stare. I want my look to change reality.”

bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze”[1]

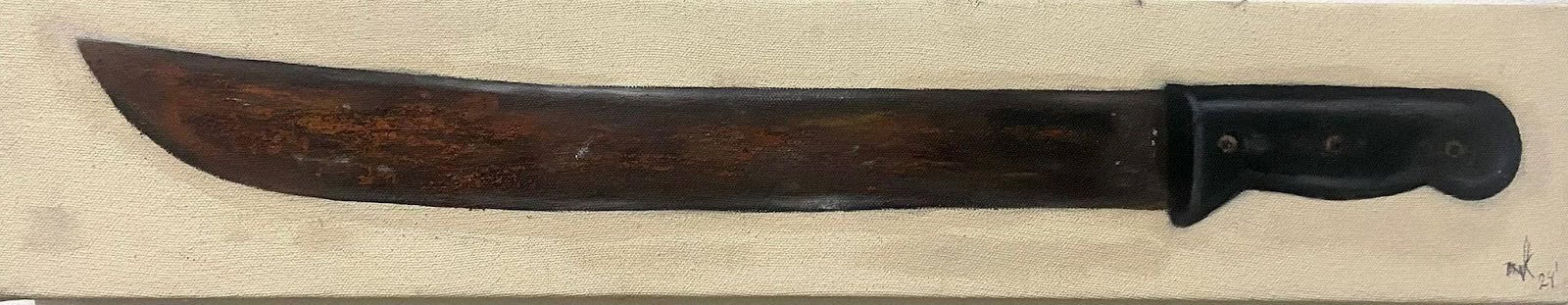

Revolution came in the form of a machete. Oppression came first. Across the Caribbean region (islands, continental nations, and diaspora), associations around the machete (or cutlass) with (forced) labor, protection, and resistance are firmly rooted in history. The Haitian Revolution, being the most prominent, continues to be a beacon for collective Black diaspora aspirations of freedom from (post)colonial trappings. Many of these sociocultural readings in the magnetic Global North, the “ongoing cultural life of the machete,” hinge on the perpetuation of racialized associations of violence with Black people across the diaspora.[2] The discussion and imagery tend to favor associations with men of revolution, the violence of empire, and the maligned coding of Black masculinities, furthering virulent racist tropes that paint Black men as hypermasculine and inherently violent.[3] This also unintentionally decenters the presence and impact of women, and associated intersectional feminist readings, of the machete in colonial histories and contemporary media.

For those living with its challenging intersections, the remnants of the colonial gaze in the Caribbean demand a specific focus. We must see how the machete’s public coding intersects race, class, and, crucially, gender and sexuality. Black Caribbean women also have deep ties to the blade, historically and in the present, and part of this legacy continues through intentional use of the iconography of the machete as commentary in creative contemporary work, which is as much a part of their legacy as the men the cutlass has been culturally attributed to, though most often to their detriment.

Enslaved African women were forced to perform field labor alongside men, in addition to the burdens of reproductive and domestic labor and community care. Yet, these women and their machete histories are generally marginalized, erased, or disregarded due to their sociocultural reading as a tool of revolutionaries, working men, and racist masculine tropes. This association of men and their swords endures, despite women taking up critical roles not only in the social ecology and well-being of those on the plantation, but also specifically in actively fighting for freedom.[4]

In Bahamian art, the machete also sings a siren song of feminine sovereignty—transcending its colonial roots as a tool of labor and defense. Caribbean women have reclaimed its iconography, tempering personal and collective meaning into the blade. From archival lens-based media to contemporary work, this ubiquitous yet charged symbol oscillates between threat and insurrection, protection and liberation. Artists like Tamika Galanis and Reagan Kemp wield the cutlass to confront dehumanizing tropes, reframing it as an object of feminine resistance and reclamation. Their work exposes how the machete’s edge cuts through history, memory, and power. Wrapped in the allure is the suggestion of violence, confrontational posturing, and an intentionally oppositional gaze—working to expose the nuanced problematics of the colonial viewpoint through which they are seen daily in their own lives.[5] The work has beauty and intrigue, but it also cuts deep at the pervasiveness of colonial thinking’s impact personally and societally.

Reagan Kemp

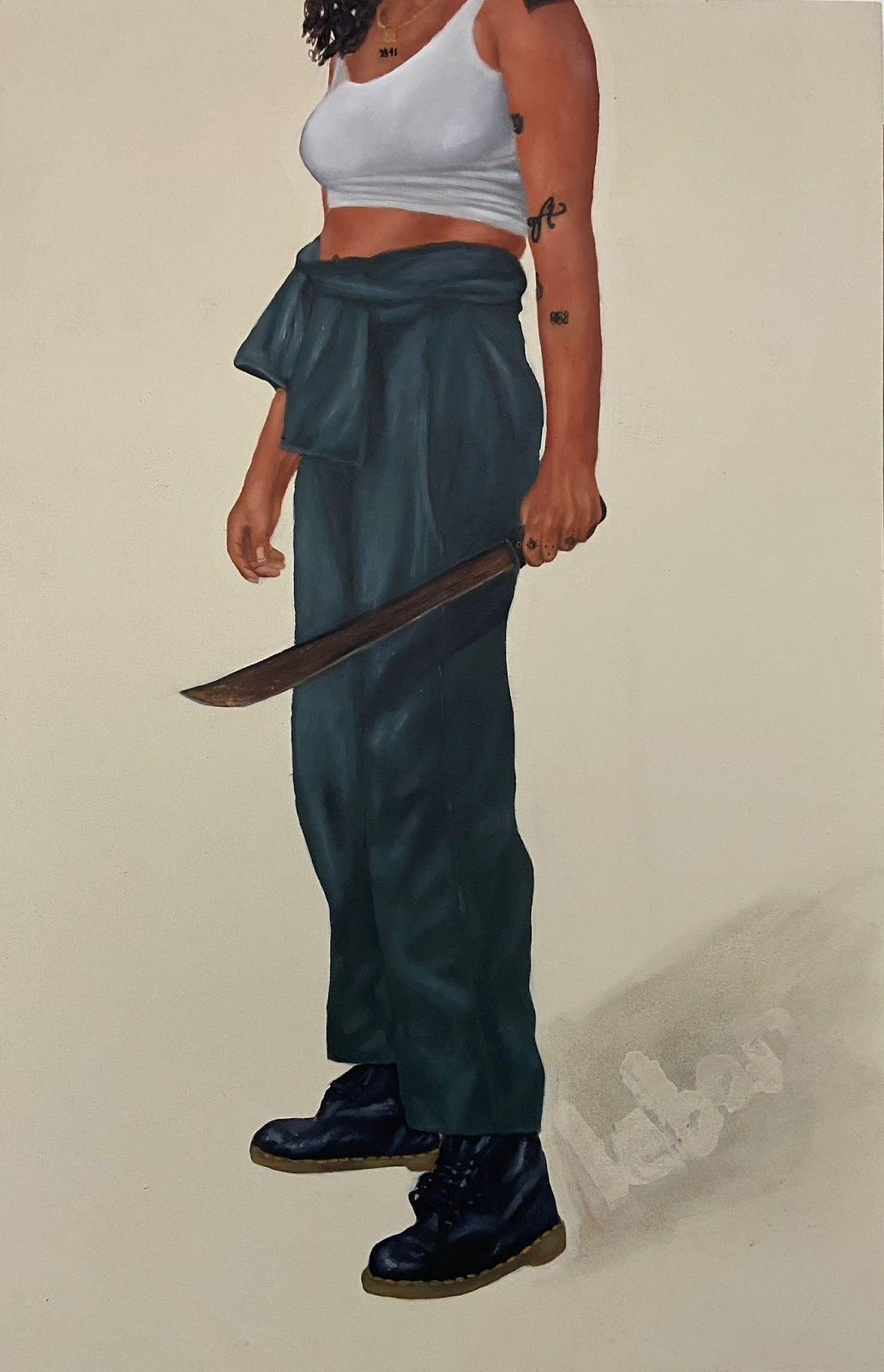

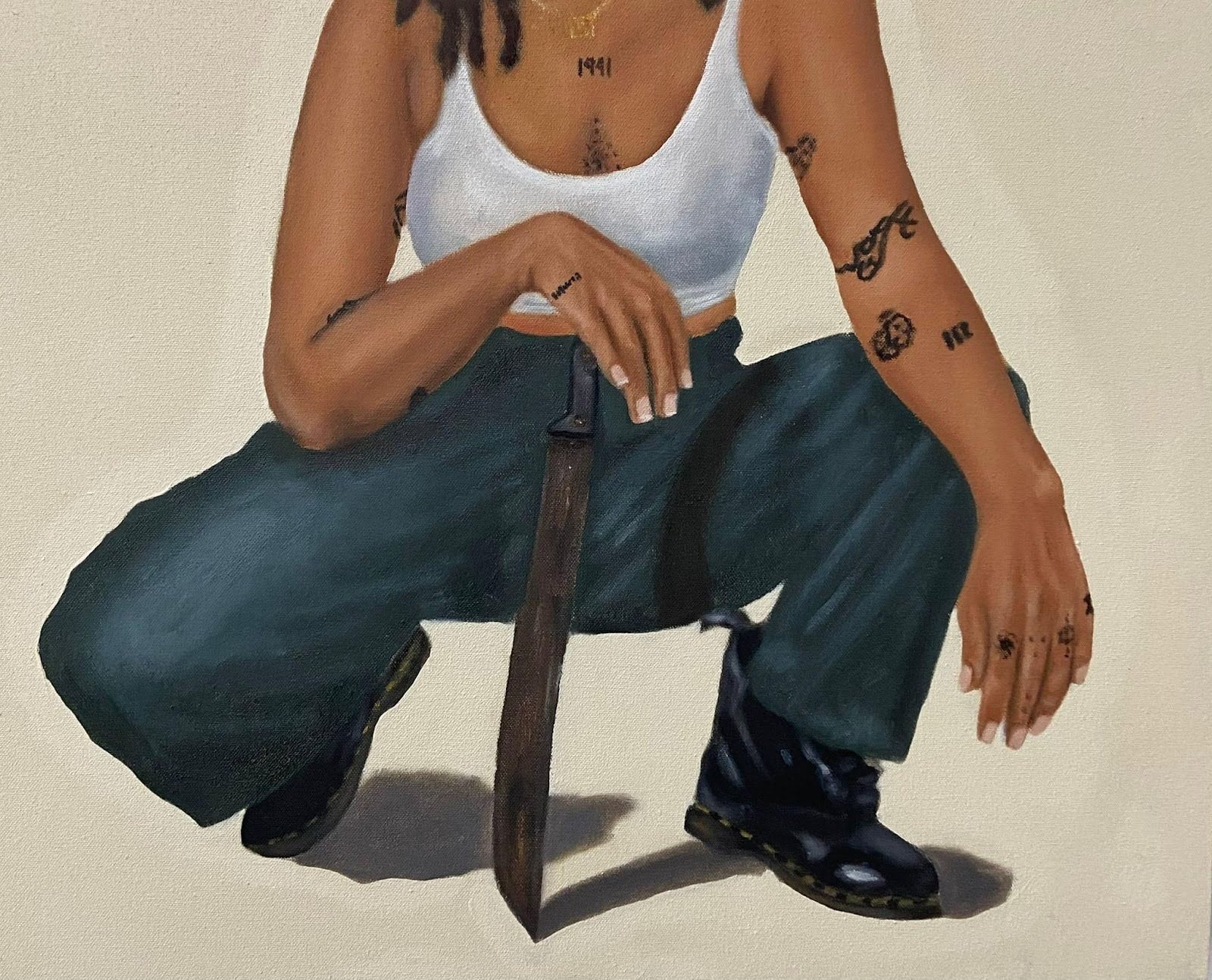

Reagan Kemp, an emerging queer Guyanese-Bahamian artist and curator based in Nassau, looks to the machete as a symbol of home, heritage, and intimacy. The series emerging from her titular exhibition I am the fruit of their labour is a testing ground for the symbolism of the machete. For Kemp, the blade becomes, in part, a symbol of trace and memory, representing the time spent with her Guyanese grandfather during her childhood in Nassau. Despite the more urban leanings of many Nassau households, Kemp grew up outside, tending to the yard with her grandfather, learning about the landscape.[6]

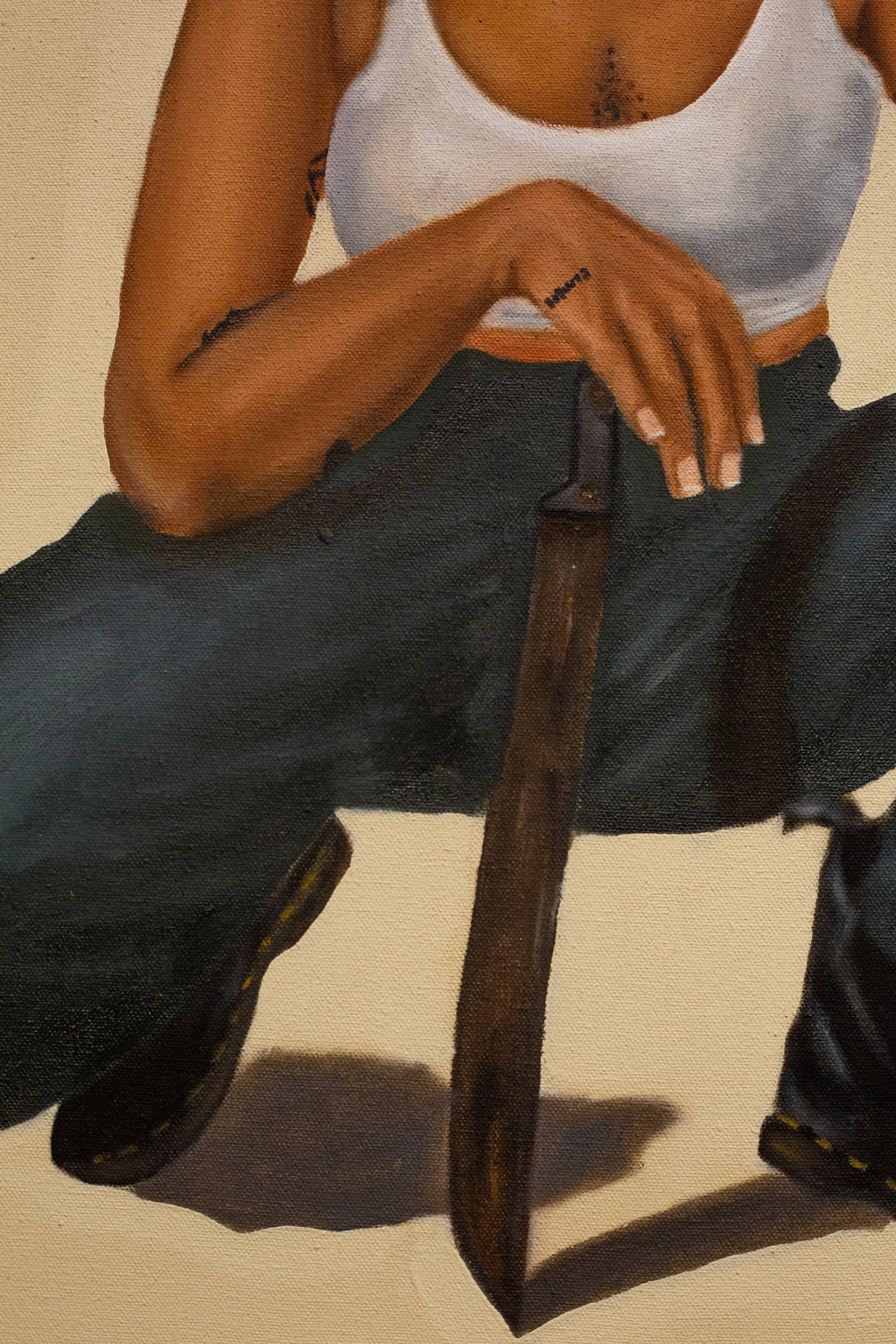

Associations with the tenderness of family memories and the honoring of ancestors are set in stark contrast to the way she uses the machete in her work, to threaten onlookers with preconceived ideas of the feminine. In her childhood, the machete was understood as a gardening implement, something tied to the grounding of the natural environment and her grandfather. In adulthood, it becomes a symbol for claiming her queer womanhood, for celebrating the way she exists as a misfit within colonially prescribed ideals that prevail in the contemporary. The playfulness of the works’ reggae and dancehall titles, along with images of ancestors and kin, become Kemp’s own lure to the viewer, threatening those who would cast colonial gaze projections her way.

The family-centered title of the series and its resulting exhibition belie the ever-present threat of violence suggested in the work: from the readiness of Kemp’s hand holding the blade in Duppy Conqueror (2024), to the confrontational lyrics-turned-title of Duppy Know Who Fi Frighten (2024). She seems relaxed when she appears in this series in her coveralls, surrounded by other images of family and flora, but still clearly poised for action if called upon. Through the self-portraits, she experiments with a posturing that initially comes off calm and confident, yet still implies a confrontational “try me.” The tool she associates most with family life and yard work in domestic spaces takes on racially rooted, historical projections of violence associated with men. Kemp leans in to threatening readings as a way to call attention to her own inherent power. Her power isn’t in the cutlass or project masculinity, it’s in her posturing, her self-identification, and in the army of ancestors and orisha—as in Maferefun Ogun (Machete Study) (2024)—implied through her positioning of the object as both domestic and defiantly protective.

Tamika Galanis

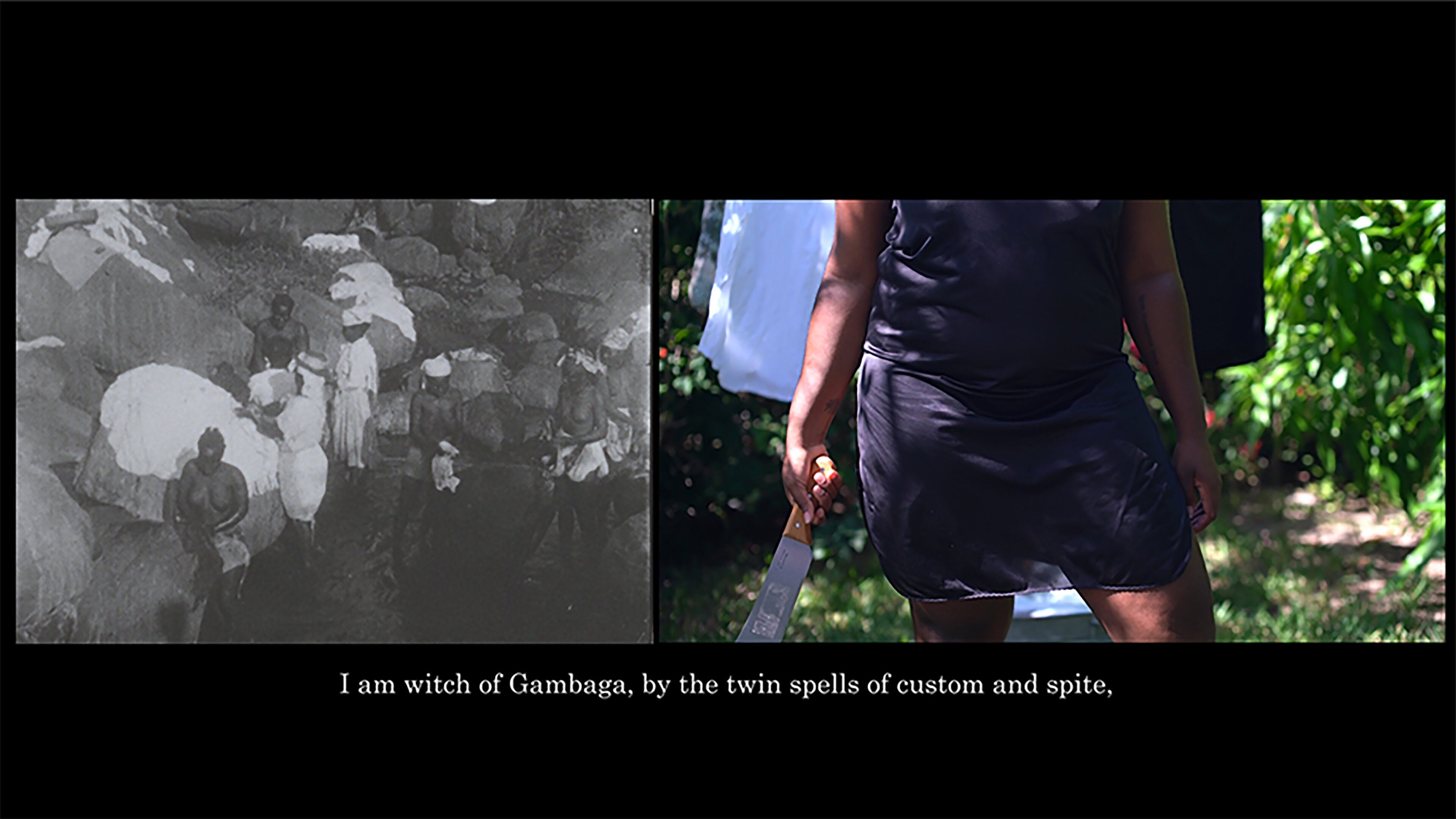

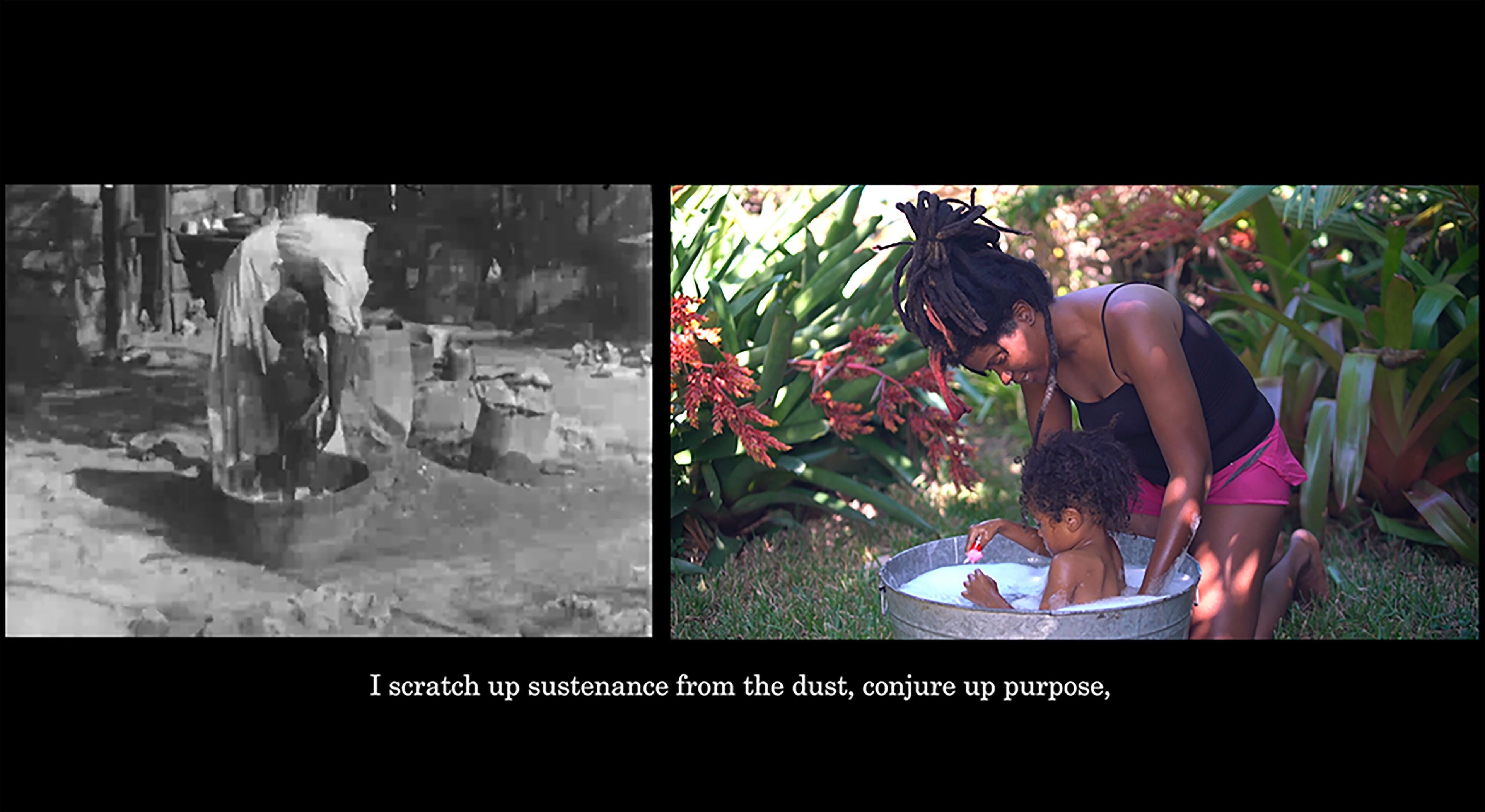

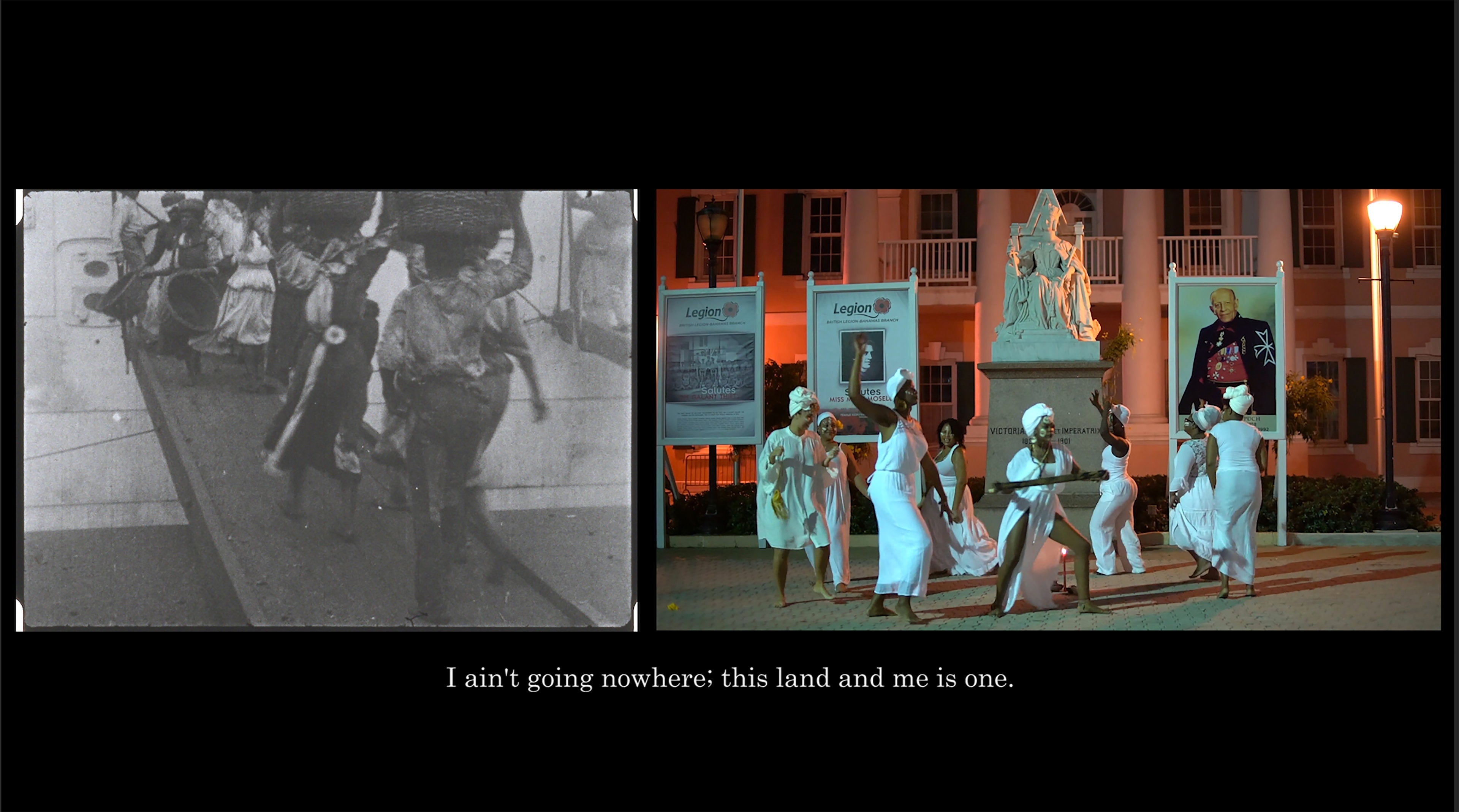

Tamika Galanis, a Bahamian contemporary documentarian and interdisciplinary artist, pointedly uses the machete in her film Returning the Gaze: I ga gee you what you lookin for (2018). The blade serves as a historical symbol of resistance and an offering in honor of ancestors, emboldening Black women. As a Jon B. Lovelace Fellow studying the Alan Lomax Collection at the Library of Congress, Galanis was drawn to early archival Caribbean footage from 1901–03.[7] In presenting her film, she posits two sets of footage for audience consideration: The first comprises copies of this early archival documentation, taken primarily of enslaved African women within the region and seen throughout Returning the Gaze. These original scenes are shown alongside footage of contemporary stagings of similar scenes and settings. This juxtaposition serves as Galanis’s response to the call from ancestors found in the archive.

Where early films show women, engaged in washing clothes or bathing a child, under a scrutinizing and dehumanizing lens, Galanis inserts contextual interpretation and agency through her own footage, including of an Ifa ritual and cleansing before a statue of Queen Victoria, or of a woman moving freely in the street in a bejeweled bra. Notably, the contemporary woman doing laundry in Galanis’s addition is now armed with a cutlass. The mother bathing her child charges at the voyeur behind the lens. These agency-saturated contemporary scenes offer a sense of late justice for the ancestral matriarchs pictured in the archival fotage. The artist intentionally armed the women in these tenderly filmed restagings, with autonomy, cutlass, and captions of empowering poetry by Patricia Glinton-Meicholas, giving voice to the silent films of the earlier departed.[8]

In its local context, Galanis centered women from her community following The Bahamas’ failed 2016 citizenship and gender equality referendum, creating a bridge between past and present equality struggles. The documentarian makes clear her vocational devotion to unpacking the “ethnographic violence” and continued exoticism and extraction of Black women across the diaspora.[9] Historically, Black Caribbean women have persistently been stripped of their agency—as seen in the 1901–03 footage. Through Galanis’s work, these subjects are now remembered and honored in ways the colonial gaze of the original filmmakers prevented.

Offering this sincere treatment—by challenging the gaze of the colonial onlooker, in comparison to her own oppositional gaze as a Black Caribbean woman—is an act of stewarding the work of healing through representation. Galanis takes a symbol of liberation of the colonial sitters’ era, the machete, and puts it into the hands of contemporary women, of descendants. Re-presenting these films in her work and taking them back to the region for display (Returning the Gaze was originally shown as part of The Bahamas’ 9th National Exhibition) is also an act of repatriation. Galanis’s gesture brings the icon of the machete and its revolutionary underpinnings full circle. This act of honoring the unnamed women ancestors of the Lomax films, while arming the women of today to enact the protection and agency they were denied in their time, is to use the cutlass as a symbol of profound reverence to the Black feminine through time. It is an act of decolonial care to these films and ancestors, forgotten in the archive and far from home.

In Bahamian art, the machete also sings a siren song of feminine sovereignty—transcending its colonial roots as a tool of labor and defense. Caribbean women have reclaimed its iconography, tempering personal and collective meaning into the blade.

The machete serves as a hinge point between the two artists’ work and as a symbol of larger themes of feminine sovereignty. The tool of oppression, resistance, and liberation finds itself to be a tool of repatriation and reparations for Galanis and a reclamation of self in Kemp’s hands. These interpretations work toward a reparative justice of representation for how Caribbean women have been imaged and figuratively erased, exploited, and exhausted for centuries. Both illustrate, from their perspectives as women at the intersection of Blackness and Caribbean subjectivity, how to take this implementation of landscaping and protection and turn it into something sacred, intimate, and empowering. This implication of the divine feminine through ritual and remembrance, and of the intimate through family ties and community, is what makes these artists’ depictions of the machete so compelling and necessary. Less about the potential for glory in resistance, they act as a rising tide of personal histories in resistance to collective feminine suppression.

[1] bell hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators,” in Black Looks: Race and Representation (Boston: South End Press, 1992), 116.

[2] Eddie Chambers, “T’waunii Sinclair and the Ongoing Cultural Life of the Machete,” Nka Journal of Contemporary African Art 2022, no. 51 (November 2022): 112, https://doi.org/10.1215/10757163-10127223.

[3] In addition to the issues of colorism maligning darker-skinned men, in particular in media, Chambers notes: “Notions of deviance and criminality became, postslavery, associations that went hand in hand with pathologies governing the Black body and its apparent suitability for backbreaking work.” Chambers, “T’waunii Sinclair and the Ongoing Cultural Life of the Machete.”

[4] Women were instrumental to Caribbean rebellions. Examples include: Jamaica’s Nanny of the Maroons; Cuba’s Carlota (La Escalera); The Bahamas’ Charlotte (1831 Cat Island revolt); and Haiti’s Cécile Fatiman, who presided over the Bois Caïman ceremony that launched the Haitian Revolution.

[5] “I knew that the slaves had looked. That all attempts to repress our/black peoples’ right to gaze had produced in us an overwhelming longing to look, a rebellious desire, an oppositional gaze.” hooks, “The Oppositional Gaze,” 116.

[6] Reagan Kemp, interviewed by author, July 12th, 2025.

[7] The collection features photographs from the Lomax family’s anthropological folk song expeditions (1934–50), documenting musicians and daily life in the Southern United States and the Bahamas. Folklorist Zora Neale Hurston, who aided their work in Georgia and Florida, appears in the collection. The Library of Congress, “About This Collection | Lomax Collection,” n.d.

[8] “Framing and activating the video’s Black feminist politics of resistance, the poem evokes Bahamian women suffering and rebelling: assigned voiceless subordination, relegated to the role of sidekick, servant to penile supremacy, daily peeling the mazorca . . . Yet, here I am, refusing reduction, head unbowed, tongue unchained; resisting devaluation of self-forged new coinage.” “Tamika Galanis,” Bahamas Film Culture Project, https://bahamasfilmcultureproject.org/tamika-galanis/.

[9] Tamika Galanis, interviewed by author, July 19, 2025.