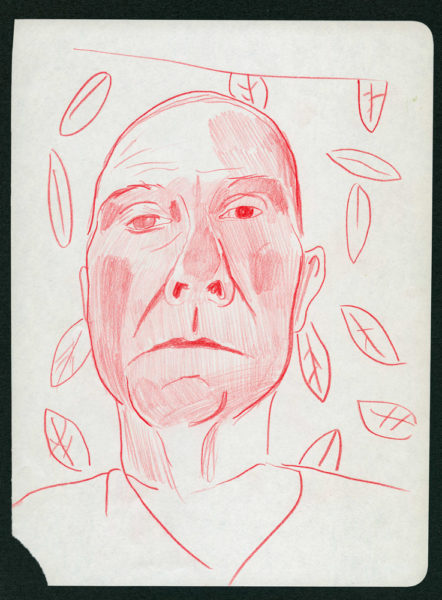

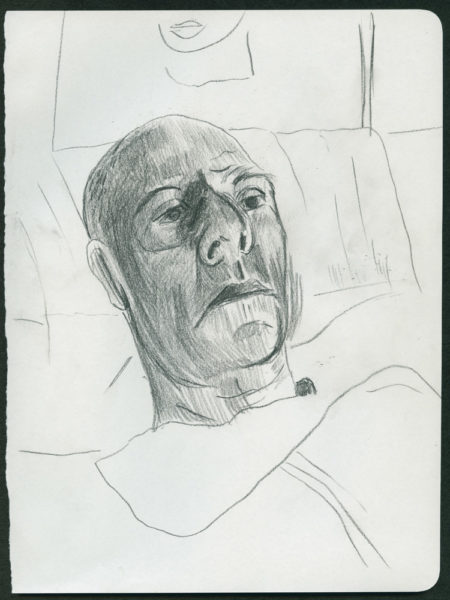

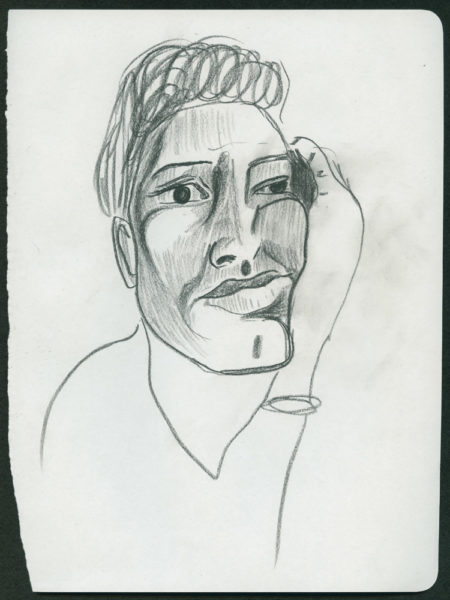

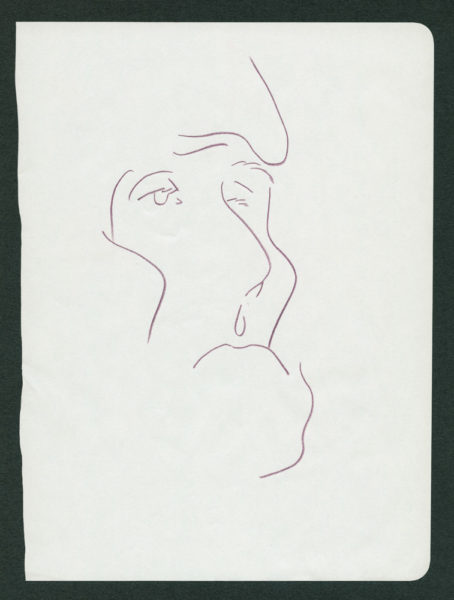

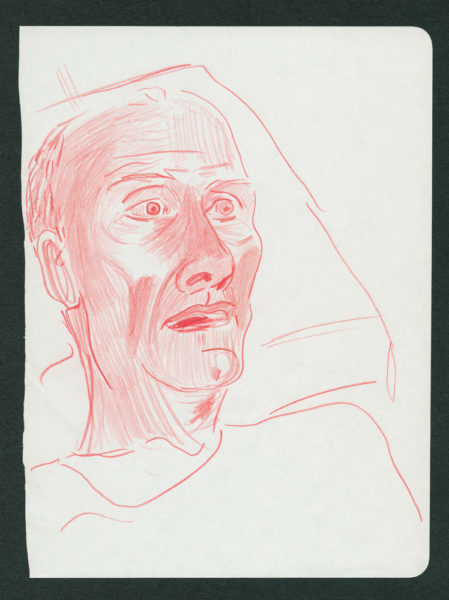

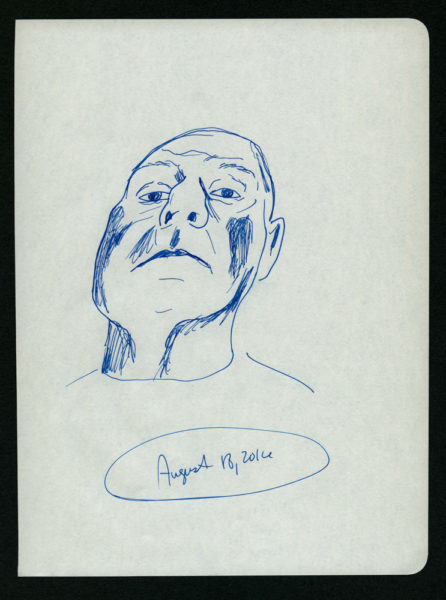

In the weeks following the opening of his first solo exhibition in New York, I interviewed Kentucky-based artist Aaron Skolnick (b. 1989, Erlander, Kentucky) about the body of work featured in “A Landscape that I know,” on view at Fierman Gallery on the Lower East Side through January 13. The exhibition is comprised of graphite self-portraits and portraits of the artist’s late husband, artist Louis Zoellar Bickett II (1950 – 2017), that Skolnick made during the last month of his husband’s life as Bickett succumbed to the incurable neurodegenerative disease ALS.

Bickett—whose life’s work included amassing an enormous collection of found object artworks made up of soil, bodily fluids, trash, furniture, books, photographs, and numerous other objects collectively known as “the Archive”—dictated several haikus to Skolnick leading up to his death. These poems will be published alongside Skolnick’s drawings in an upcoming publication from Fierman. A selection of drawings from this series will also be included in the 2019 Atlanta Biennial co-curated by Phillip March Jones and Daniel Fuller, “A thousand tomorrows,” which opens on January 17 at Atlanta Contemporary.

The drawings are startlingly intimate, frequently graceful, and occasionally disturbing. In our conversation, Skolnick and I discussed how and why the drawings were made, the frequently collaborative nature of the two artists’ relationship, and the challenging and transformative possibilities of being a caretaker and being taken care of. This conversation took place over the phone in December 2018 and has been edited for publication.

Paul Michael Brown: Can you provide a brief overview of the work that’s currently on view in the show at Fierman Gallery and that will make its way to the Atlanta Biennial in January?

Aaron Skolnick: I made the work the last month that Louis was alive. He had asked me to draw him to help me process what was going on, the whole moment. And when I started drawing him, I started to think about the body as a landscape and what that meant when he was bedridden. For the last two years of his life, I was his caregiver, so our relationship had changed so much. The idea of what intimacy was changed between us.

As a caregiver, I fed him in bed, and even when he wasn’t fully bedridden, I was still overprotective. I quit my job to take care of him three weeks into him being sick. I’d work in the studio on and off. I was really anxious. He was like, “You need to do something,” so we talked about me drawing him. He understood the importance of it for us personally, and how important it was for people to see that moment and for my work. He was always so aware of everything. He thought of everything in terms of the work. Like, as you know, in making the Archive, he considered where everything could be made important. Every single moment was important for your career and your work.

He made work until the very end—I think two days before he passed he dictated a tag to put on a teddy bear. He was like, “You need to make work too.” And it became this really nice way to sort of go back in time a little bit, to get to draw him and think about color. I thought about color in such a different way. I wasn’t able to come up with these very complex things, of course, because I was so anxious. But yeah, especially as nurses and family were coming in and out more and more and more, making drawings was a really good way for us to connect in those final moments.

PMB: You mentioned starting to see his body as a landscape. Can you expand on that?

AS: At some point, all the memories started flooding in, and I started to think about when I started dating Louis. We had our bed upstairs, and we would lie in bed before he had to go to Lucie’s after he had been working in the studio, and I would take a break, and we would be naked, and I would touch his chest and rub all over his body. It was that moment when you realize you’re really in love with someone, past that initial moment of lust. I would just stare at him, and he would call me his “Ari boy,” and I remember just thinking that the body was a landscape: all its little bumps and indentations, the legs and thighs, his chest, his arms, everything. I just realized that our bodies belonged to each other and that there was this beautiful, intimate landscape that we made together. And then I realized that the landscape had changed and all that could really function was Louis’s head, in that intimate sort of way, because the rest of his body was so frail.

I wanted to show this really intimate moment in the drawings. I feel like it needed to be shared to show people my relationship and—not to be cheesy—but to show what love can be, and what a relationship can be. I thought it was extremely important to talk about intimacy in the gay community, because it’s not about sex, and it’s not about a sickness that has a big political agenda that people can rely on to view the work. Being gay is already political, and I didn’t want this to be—there’s all this work about gay intimacy, but I feel like a lot of it is very similar. I felt like this show was really needed—not necessarily to show the opposite, but to show another side of what life can be, or what life ends up being for a lot of people, whether from sickness or old age. I was just confronted with it at a really young age.

PMB: I think this was the case throughout your entire partnership, but I think you guys were really collaborating with each other. You were being his hands for the Archive, and then you were, in turn, using his body for your artwork.

AS: Oh yeah, I would definitely agree with that statement. We did. We were together for eight years, and for the first six we shared a studio and home. He worked downstairs, and I worked upstairs. We never got sick of each other. It was really strange to have that sort of relationship where you can work within that tight of a space and also both be artists. Because to be an artist, you have to be incredibly selfish. Louis and I only really had one rule for our relationship, and it was that we would break up if one of us tried to come between the other and his artwork. That was the number one thing that was important to us.

As things changed, I gathered all the dirt [for the Archive]. I didn’t want him to stop making work. And people thought that I was nuts for doing things the way that I did. They said I was doing it wrong, like, “You need to spend time with him in a more intimate way.” But this is how we were intimate. We wanted to make artwork, and I wanted him to keep doing things. Louis understood and I understood that the period was coming at the end of the sentence, like he said in the documentary I Was Here [a short film by Julian Dalrymple].

He was very aware that this thing, the sickness, had become a part of his artwork. To quit everything and ignore it just wasn’t who we were. It just changed everything, and it all became about that. Especially towards the end, making work together was this beautiful way to recognize things and have conversations with Louis that were just the two of us.

PMB: There was a significant age difference between the two of you, so, in some respects, while getting involved with someone that much older than you, there may have been an expectation that you would likely be his caretaker at some point.

AS: Yeah, 40 years’ difference. Louis didn’t want to date me at first because he was afraid that he was going to get sick and that I was going to have to take care of him. He kind of predicted what ended up happening. I was just like, “Will you go on a date with me? Can we try it? We really like each other.” He was like, “No, I don’t think we should—you’re really young.” We went on a date after I convinced him and then decided it was a thing we needed to try to do. It just kind of fit together so naturally.

PMB: I don’t think this is necessarily where your work comes from, but I’m interested in this work and practice as a way of documenting a very queer relationship to intimacy, finding new ways to relate to another person’s body in a way that doesn’t involve sex as we normally consider it.

AS: Drawing was a way for me to come back to his body. You’re not sexually intimate when someone is sick like that. The role changes. It was a way for me to come back and examine his body with my eyes all the time. To come back and touch his arms again and feel his ribs and his chest all over again. Somebody else was bathing him at this point, so I didn’t have to do it. He was too fragile for me to do it. They didn’t trust me the last couple of days.

It’s a privilege to take care of someone. I say it in a funny way, but I mean it very seriously as a point of reference: like Sally Field freaking out in a cemetery over Julia Roberts’s death in Steel Magnolias. You can laugh because it’s kind of funny, but she says something like, “I can run a marathon, but my daughter can’t. I can do this, but Shelby couldn’t.” I totally related with that character because Louis couldn’t do all these things that I could. And she goes, “Nobody else could handle the hard stuff at the end, but I could.” I really related to that.

When they were taking his body out of the apartment, they told me not to look, but I had to see it through to the end. I had to see the full moment. I had to witness every part of Louis Bickett. I couldn’t not do it, it was like a weird ceremonial thing. I had to see the last moment of him leaving the apartment. I just relate to that moment of feeling so honored to take care of your partner. It was such an honor taking care of Louis. He had the biggest personality and being able to break through that and get to him was just… yeah.

PMB: Correct me if I’m wrong, but a lot of the drawings were made after his death from memory, right?

AS: A couple of them were, yeah.

PMB: What was that process like for you, revisiting his image after he died?

AS: I made some immediately after he died, so it was more anxiety-induced, like—I have to do this. I wanted to see Louis right before he got sick. Because the minute someone tells you that they’re sick and they’re dying, you look at them so differently. I was with him every day, and I didn’t notice the changes as much as everyone else. Like, one day, I walked in the house and was like, “Oh my gosh, he’s really really ill.” It was weird to go back to that moment for me.

PMB: When was the first time you looked back on the whole thing as a body of work? What was that experience like?

AS: I made my mom look at the drawings last Thanksgiving. I got the work out and realized how struck she was at our relationship. I realized that it was a body of work and needed to be shown.

PMB: Can you talk about Louis’s poems and the connections between them and the drawings?

AS: I think the connection is about Louis letting go of life through the—hold on, I’m going to pull up the poems really quick.

Okay, so “My Death Haiku #8” goes:

Arms already dead

the legs are soon to follow

death is awaited

It was this way for him to release and get these thoughts out, and the drawings were a way for me to get that release with him as well. It was like engraving, engraving someone, trying to capture someone in their final—it was a way for me to start to let go. The haikus were a way to let go of him within this realm.

I’ll never leave Louis. I think he was the love of my life.

Where’s #16, the last one? Oh, here, “My Death Haiku #16”:

The end is so near:

SLEEP PAIN LOVE

is all that remains

I think that I am done

He had finally realized that it was time to let go. I think the strangest thing about the haikus was that he dictated them to me. I wrote all of them down and didn’t realize how heavy they all were until a month after Louis had died. I just had this thing that I had to do for him.

PMB: I remember talking to you a few times, maybe in the last six or eight months that Louis was alive, and I think that even then you were aware that he was very intentionally keeping you busy. I mean, I know you relatively well and know that you’re kind of naturally a somewhat anxious person, so to see him try to care for you in that way and keep you occupied with things that were also instructing you on how to work through everything was pretty amazing to watch from the outside.

AS: Louis definitely kept me busy, and I think part of it was keeping my mind busy.

PMB: Do you think that making the drawings was mostly just something that was keeping your mind off things, or was it therapeutic in other ways?

AS: For me, it was a way to connect to how things used to be. Louis and I chose to not have a lot of help a lot of the time so that it could be just the two of us. Because once help starts coming in, it doesn’t stop. Once someone is dying and they start to mentally release as well, then the body stops fighting as much and sort of gives into death. I really couldn’t stand it, all the people being in our house all the time and trying to talk to us. For me the number one thing was being able to connect with Louis and being able to sit next to him and draw him and take him in in this intimate way. Because I couldn’t lie in the bed with Louis for the last eight months he was alive. I couldn’t sit in the bed because it was a hospital bed. The only thing I could really do was sit next to him and hold his hand and draw him.

Aaron Skolnick‘s solo exhibition “A Landscape that I know” is on view at Fierman Gallery in New York through January 13. A selection of the drawings on view in that exhibition will be included in the 2019 Atlanta Biennial, “A thousand tomorrows,” opening January 17 at Atlanta Contemporary in Atlanta.