Welcome to The Fringe, a twice-monthly column curated by Kristin Juárez connecting Atlanta to the international art world. See the curator’s note below to learn more.

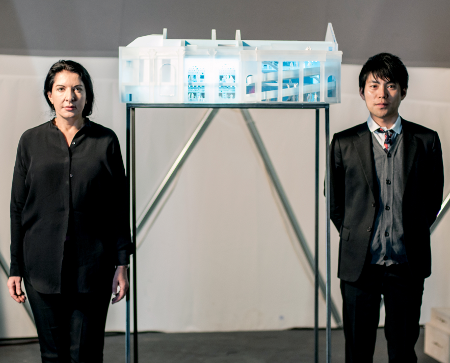

For many who attended Belgrade-born, performance artist Marina Abramovic’s lecture in Atlanta last year, it was the first time they had heard of what the artist has dubbed her “tangible legacy”– the Marina Abramovic Institute for the Preservation of Performance Art. Abramovic revealed the design by famed architect Rem Koolhaas, along with Shohei Shigematsu of the OMA firm, for her institute this May, but the project has been in the works since at least 2007, when the artist purchased the property located just two hours north of Manhattan in Hudson, New York. Abramovic, in the meantime, has been the subject of a major retrospective at MoMA, with her three-month performance The Artist Is Present grounding what turned out to be a blockbuster show. Her work has fueled public curiosity and criticism to the extent that it has allowed Abramovic to become something nearly impossible in the avant-garde art world: a performance art celebrity. Yet after 40 years of creating physically demanding, often grueling work, it would be hard to deny that her notoriety is not well deserved.

It is this very sort of star-power that will be necessary to turn Abramovic’s institute into a reality. Her center, situated in a 1929 structure, which in previous lives has functioned as both a theater and indoor tennis court, will not host the expected exhibitions of major arts institutions. Instead, the programming will be highly focused on ephemeral, time-based performance art. Time, indeed, will be of the essence: the briefest performances will last a minimum of six hours; the longest, perhaps a year. Abramovic has long been an ardent advocate of the durational performance piece, and saw the need for a center which honored performance by establishing an archive and offering a space for artists pursuing durational performance to develop and show their work.

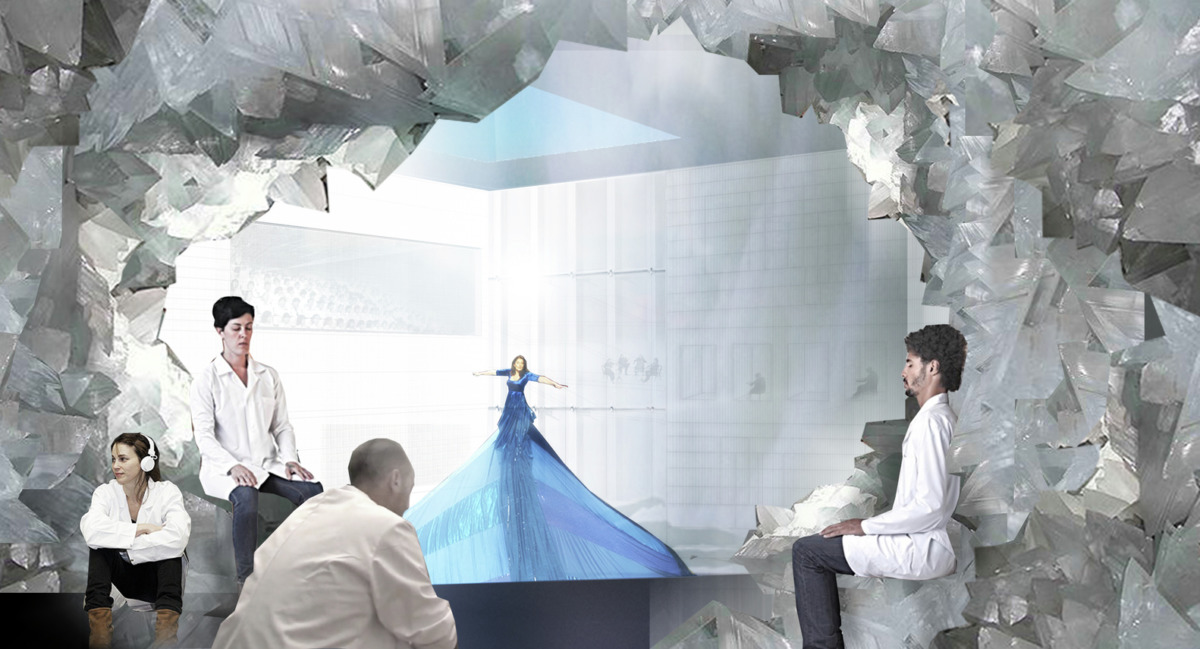

Underpinning the mission of housing long-durational performances is Abramovic’s intentions for the spectators who would enter. The longer one looks at the plans for the institute and the artist’s stated mission behind it, the more one realizes that the organization is less about the performers, and more about those who view the performances. Believing that training the audience to see and experience long works is critical to the institute’s success, spectators will be introduced to what the artist calls the “Abramovic method.” Visitors to the institute must sign a contract in which they agree to surrender a certain amount of autonomy: they must stay a minimum number of hours, they must don white lab coats (embroidered with Abramovic’s name) over their own clothes, and they must temporarily relinquish personal technology devices that connect them to the outside world.

These mildly authoritarian injunctions go far beyond the art world’s frequently meaningless invitations for the audience to become “part of the performance.” As anyone who has lived under a dictatorial regime will attest, the act of surrendering control has the effect of inducing a sense of vulnerability in the one who surrenders. Abramovic has more than a passing familiarity with such conditions, growing up in Communist Belgrade and raised by parents who held well-respected occupations in service of the State. Vulnerability is what unites Abramovic’s performance history, which parallels a well-established spiritual tradition in faiths across the globe: allowing oneself to become vulnerable to enduring pain and difficulty leads to transformation. It is clear that over time, Abramovic has shifted her focus from plumbing the depths of her own personal pain to attempting to make the transformative available to others. Using time and personal connection as her vehicles, vulnerability remains the constant undercurrent. In manufacturing a precise set of conditions which introduce (admittedly mild) discomforts to the institute’s audience, Abramovic promises they will receive something in exchange – transformation, perhaps even transcendence.

The other mission of the institute is to create an archive of performance art. The usual documentary forms – video and film, photographs, transcripts of testimonies, and ephemera, for instance – will make up a portion of this archive. Abramovic has managed to retain a remarkable amount of material covering the duration of her career, and this body of evidence will find its home at the institute. Before one assumes that the institute is at risk of becoming a “Museum of Marina,” however, it should be noted that Abramovic has long recognized the dearth of material that exists for the storied breakout performances of the 1960s and 70s. She is deeply concerned with performance art’s future, and sees its past as a critical component to shaping what it might become.

Indeed, the problem of how performance art is best documented has gained increasing currency in the wake of Abramovic’s Seven Easy Pieces, which she performed at the Guggenheim in 2005. During this piece, the artist re-performed her own work as well as seminal performances by artists such as Gina Pane, Valie Export, Vito Acconci, and Joseph Beuys. Re-performances of Abramovic’s own works were also key in 2010’s The Artist Is Present. The possibilities that unfold from archiving performance through re-performance–by crediting performances to their original authors while offering new interpretations of them–are manifold. In Robert Blackson’s article for Art Journal, “Once More … With Feeling: Reenactment in Contemporary Art and Culture,” readers are reminded of the ancient Greek historian Herodotus, whose, “hope was to pen a live document–a text that would activate rather than pacify, and through this activation the deeds of the past would alter the future. Reenactment recognizes and ‘performs’ this forked tongue of history, at once implying authorial insertion through personal experience and conversely reinstating its determined objectivity with empirical information (or facts).” To be sure, the reinterpretation of former work promises a more fluid archive than the records, receipts, and microfiche that inhabit the usual files found in an archive. As performance scholar Diana Taylor has noted, knowledge can be transmitted through both archival and embodied means. The plans of the institute are encouraging in their efforts to uphold a space for both.

While the possibilities arising from preserving something inherently ephemeral are ripe, so are the problematics. Part of the appeal of performance for young artists of the 1960s and 70s was the way in which the genre offered a space to counter the cultural elite of the day. The thrill of creating work which refused to become a commodity – work which served to bolster neither fusty museum directors’ reputations nor unscrupulous art dealer’s pocketbooks – fueled much performance in those early, heady days. Those pioneering artists would have found the very concept of a performance art celebrity absurd. Jump to the current day, however, and one finds that institutional critique has firmly established itself in the most hallowed halls of culture, and the cultural elite now routinely–lavishly, even–feed the very artists who bite its hand. The promise of international art fairs and opening night extravaganzas are palpably removed from the revolutionary gestures of performance art’s origins.

Though it may be impolite to say so, the commodity value of works of art which cannot be sold is certainly not lost on art dealers with recognized performance artists on their roster. Few fail to understand the “mo’ media = mo’ money” dynamics that occur when a powerful name can easily reap rewards on a par with saleable products. Consider the case of Abramovic’s dealer Sean Kelly, who recently re-staged Abramovic’s and Ulay’s 1974 performance of Imponderabilia in one of the two entrances to his booth at this year’s Art Basel in Switzerland. Even as several bloggers commended this re-staging as a successful integration of non-commercial work into a frankly commercial fair, the Wall Street Journal was quick to announce Kelly’s success in unloading videos of the original performance (at $225,600 each). Then there were last year’s charges of spectacle and exploitation surrounding the performances Abramovic directed for MOCA’s annual gala fundraising dinner, with major arts voices such as Yvonne Rainer and Douglas Crimp voicing their objections to the conditions surrounding the affair. In a telephone interview this May with the New York Times, Abramovic declared, “The most revolutionary ideas are not sellable, but only mind-changing,” but it seems irresponsible to continue to suggest that the genre exists entirely outside the reaches of commerce.

Commerce–and plenty of it–will be needed to make Abramovic’s institute a reality. Her name, as well as that of Koolhaas, should help draw the estimated $15 million necessary to begin breaking ground (despite the ironic twist that Koolhaas continues to reside in Amsterdam in part due to his distrust of American-style “celebrity culture”). How the OMA design will unfold raises some especially profound questions regarding how an architecture of performance is to be realized. In the Times report on her institute, Abramovic listed her requests of the OMA designers, among them being a levitation room, a digital temple, and “a room for drinking water and drinking water in slow motion.” Described in this way, the institute becomes about as far removed from reality as it is from Manhattan.

The Abramovic-Koolhaas alliance should pique architecturally-cognizant Atlantans’ interest. Some will recall his 1995 publication Atlanta. In the book, the architect pointedly criticizes omnipresent architect/developer John Portman, noting that “with these two identities merged in one person, the traditional opposition between client and architect – two stones that create sparks – disappears.” With the Abramovic name so deeply imprinted upon the project, will there be room for that “spark” to appear?

While performance has long been a staple of the art world, its institutionalization is a more recent phenomenon. Locally, the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center is one institution which locates performance as the backbone of its summer exhibition, Deliverance. It may not be possible–nor desirable–to franchise Abramovic’s institute at satellite locations, but it is worth considering how audiences far from New York can experience performance and how these performances are documented and remembered. Meanwhile in Hudson, watching the materialization of Abramovic’s archive and playground for performers and their audiences should prove nothing short of fascinating.

About this column:

The Fringe seeks to make greater connection between Atlanta and the art world at large. Now with writers contributing from around the country, the column continues to follow contemporary art that addresses the unique qualities of the natural, built, and social environments. The Fringe will unfold as several collections of articles bound together by a theme.

Alana Wolf’s article is the second in the collection I have named “Life as Form” after Creative Time’s second annual summit. The correlating exhibition entitled Living As Form combined artists, theorists, curators, and activists to consider how creative projects can restructure relationships between people and the places they live. Similarly, BURNAWAY will reflect on artistic form and public engagement in projects based in Los Angeles, Chicago, New York, Charleston, Berlin, and Atlanta.

—Kristin Juárez