[cont.]

Back inside, Maggie examined the drawings of the babies. Most work about children focuses on the cherubic little faces and the cuteness of the pudgy body parts, invariably rendered in shades of soft pastels like tinted talcum powder, all shapes curves and curls. Everything sweetness and light. Lori’s drawings were actually more visceral than her sex paintings had been, acknowledging real conflict about motherhood. No, that’s not exactly it. She seemed to genuinely love them. The drawings just exploded any notion that babies are unmitigated bundles of joy: in these drawings, orifices, all orifices were the focus. Orifices excreting the colors of what orifices actually excrete. These were brutally honest about it. Poor Lori. She must really hate baby barf and changing diapers and who could blame her? No sane adult enjoys playing with poop. Looking at the excreted colors, she could vividly remember the sound of Momma gagging over dirty nappies, or maybe it was just another round of morning sickness. That gagging sound was pretty much a constant in her childhood.

The gallery was empty, as it often was on Thursday, leaving Maggie too much time to brood. Since she left Barbara and started up with Madison, she had been trying to piece together what was going wrong, why she got together with either of them in the first place. Thursdays were apparently reserved for soul searching. But even the drawings couldn’t lure her completely away from obsessing about it. Mothers were the root of it. Mothers always fail on some level, don’t they? Sustaining unlimited patience and kindness 24/7 is a superhuman feat. And any failure, regardless of how small, exerts so much impact on children, on self esteem, on how the children engage in relationships. Or don’t have relationships.

All three of them had one important element in common: they were raised by mothers who had been systematically belittled by their husbands and that fact skewed their relationships, imprinting a network of cracks on the surface of their crystal ball. If life is a dance, as Miss Tillie used to insist, she and Barbara and now Madison were in urgent need of a choreographer, someone to teach them how to dance in unison with your partner. No, that’s not it. All she had to do is let them take the lead. They both wanted so fiercely to lead, to dominate, to control.

Those who need to control are not in control. Miss Tillie told her that. What was the other adage Miss Tillie used all the time? Do as I say, not as I do, to which she always added, you need to learn from my mistakes otherwise they are wasted.

Learn from your parents’ mistakes.

Maggie wondered if she selected partners so obviously like her father so that she would never allow them to get close enough to do the kind of damage her father exacted on Momma. After all those years of sporadic beatings, watching Momma cower, she already had the know-how to deal with his kind of onslaught: the walls to protect herself were already in place.

Self preservation at all costs. What was the other option, though? Those who don’t learn are doomed to repeat. And what lesson did their mothers teach? That wanting so badly to be married and part of something bigger was a hoax. Really what did it get them? Roger married Rina for access to the moneyed class as much as for her beauty and he came to hate that dependency. Rina married him because all of her friends were married and her father actually approved of him. Father knows best. Madison’s parents married after college because it was expected of them. She lived to shop; he worked in banking. She thought he was boring; he thought she was mindless. They ended up hating each other and their children. Divorce didn’t solve the problem. Both of Madison’s parents married and divorced multiple times, never quite getting it right. Maggie’s father married her sixteen year old mother because he got her pregnant. He was a career military man, born and raised in exotic Louisiana, and had seen her in a polka dot dress drinking soda pop, seduced her over the course of two days while on leave, and left the area. Sometime between the conception and her birth, he had found his way back to Jesus and that prompted him to return to do his duty and marry Momma. He was 27 and named his ill conceived daughter Magdalena after Jesus’ prostitute follower so Momma would never forget her weakness in having sex with him before marriage. She had quickly agreed to marry him because he was her ticket out of Alabama, away from her parents. You’d think they would have threatened to throw her out because she sinned and got pregnant out of wedlock, but what made them so furious was that he was Catholic, he wasn’t from there. And that had been a good part of his draw. It’s so bald, isn’t it, when you redact the initial euphoria of love and lust. Love itself seems so special at the time. Only later, after it’s faded, do the tawdry underpinnings display themselves. Only later do the boundaries between the inner chaos of desire and the outward order of manners and expectations become so very clear.

Maggie wouldn’t blame her problems on Momma, though. Momma did the best she could. Besides, it’s never just one cause, one root, one source. The avoidance of intimacy could as easily be blamed on conditioning from her father, staying as removed from him as possible to escape his belt and sharp tongue. And then there was the constant moving undermining any sense of permanency in her friendships. Even seeing how much Miss Tillie enjoyed living alone was a factor. It’s never just one thing. As Dennis used to say, life is a complex equation.

Just Like Suicide pt. 18

Related Stories

Daily

Features

Reviews

In the Studio with Chayse Sampy

Amarie Gipson visits mixed-media artist Chayse Sampy in her shared studio in Downtown Houston to discuss living in the South, Afro-surrealism, and the color blue.

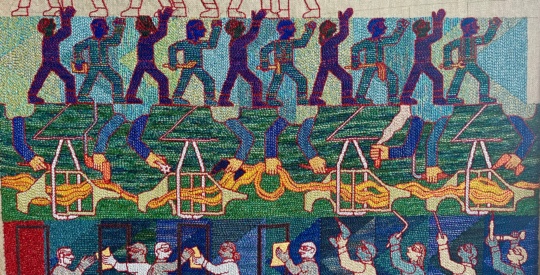

Weaving Work: On the Tapestries of Tabitha Arnold

Lina Alam profiles the spiritual allegories and the labor of weaving works created by Chattanooga-based artist Tabitha Arnold.

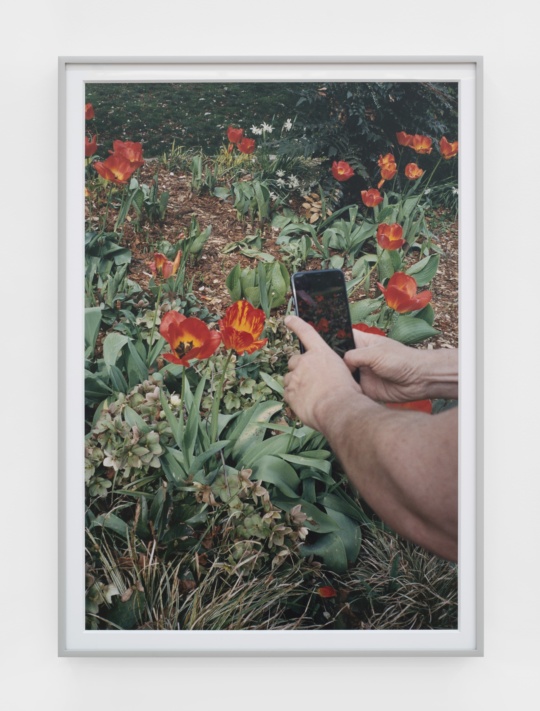

A Landscaped Longed For: The Garden as Disturbance at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum, St. Augustine

Christopher Stephen reviews the visual metaphors of the garden found in A Landscape Longed For: The Garden as Disturbance at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum, St. Augustine.