Doug Wheeler’s much anticipated installation PSAD Synthetic Desert III opened at the Guggenheim on March 24. It was the newest installment in his series of immersive “infinity rooms.” This dreamy, perception-altering space is a semi-anechoic chamber inspired by Wheeler’s trips to the Mojave Desert. He began his drawings for this piece in 1968; this is the first time the project has been realized. After months of gawking over the single, mind-bending promotional photo circulating the Internet, I had to see it for myself.

I stared at that photo many times over the first half of this year. I must get to this place, I told myself repeatedly. The installation was no easy feat to access—and certainly not by the time I got to it which was, admittedly, the second-to-last day it was on view (it closed August 2). Only five people were allowed in the room at a time and only for 10- or 20-minute blocks. The 20-minute passes were sold out well before the exhibition closed. All that remained when I started planning my trip to New York were 10-minute passes doled out on a first-come first-served basis. The museum opens at 10am.

During my first attempt that Monday, I strolled into the museum at 11am hoping there would still be tickets left: I was wrong. The person working behind the counter said they were sold out and, essentially, good luck getting in tomorrow. I asked her what time I should show up the following day to ensure I could get in (my flight was leaving the next evening and I was determined to see this damn room.) She said I should get there half an hour before the museum opened to get in line.

I showed up at 9:20am the next morning to be certain I snagged a ticket. There was already a line forming outside the door that grew longer and snaked around the side of the building until the doors were opened. We were escorted into the museum and given our golden tickets (I think mine was glowing). By 10:35am tickets to the installation were sold out for the day. Visitors approached the installation’s primary entrance in droves only to be turned down when they asked how to buy tickets.

By the time my viewing block arrived, the 11:00-11:10am slot, I was elated. I felt like I was about to meet the Queen, or skydive, or take a brand new drug for the first time. On the top floor of the museum, a staffer ushered us into a quiet waiting area 15 minutes prior to our viewing. It functioned as a transitional space, mentally and physically. The five of us sat there quietly while the guide explained some ground rules: no talking inside, no cell phones or devices, Sir, can you please remove your watch?, Ma’am can you take off your jacket? It makes a swishing noise, try to pick a spot a stay there, feel free to lie down or sit however you wish, just please try to be still.

Finally, our time came, and we were lead through one door, and another, and another, and then: ta-da!

The purplish hue enveloped everything. Hundreds of sound-absorbing foam peaks lined the walls and floors. The room was true to the photograph I’d been ogling, with a few key differences. First, the room feels small when you walk in. You notice the walls are not far out of your reach. The spiked pyramid wall design is inspired by the standard anechoic chamber. Wheeler’s room is a “semi-anechoic” chamber, meaning it is specifically designed to drastically minimize sound, though does not eliminate it completely. Nevertheless, you cannot even hear lights buzzing or any ambient noise from the crowded museum floors below. It is the quietest place in all of New York.

When you walk in, you can gauge the size of the room with some degree of accuracy because the illusion has not yet set in. The thing with Wheeler is, like most the Light and Space artists, you meet him halfway. He gives you the setting to experience transcendence; you, as the viewer, do the work to perceive it. It is, in the purest form, a co-creation, a collaboration between artist and viewer.

You pick your spot on the T-shaped walkway and sit down. If you are lucky, a striking, visceral moment occurs in Wheeler’s room. After about two minutes of silently gazing out into the space, your mind experiences a “switch” of sorts. Your vision loses bearing on reality: it detaches from its normal anchors and suddenly the room is infinite. You are transported to a reality separate from the one you inhabited moments ago. At the risk of sounding cliché, it feels like you’re on another planet. It takes time and effort to get there, but when it happens, it is unparalleled, moving, divine.

I couldn’t help but wonder: did the restrictions make the experience better? That it was an obstacle course to get in the door hadn’t turned me off at all; in fact, it enhanced the experience. In my case, I’d flown over 800 miles, failed once before, gotten up way too early, hungover and heavy-eyed, to sit in traffic for 45 minutes, to wait in line for another 40 minutes, to wait an additional hour for my ticketed time. That’s kind of a lot for 10-minutes in a quiet room, no? But when I stepped foot in that room, I reveled in it. I let myself be fully immersed. And there’s something important about all that. I could not take the experience for granted: I’d invested too much.

That said, even just a few barriers put in place—10 minutes only, 5-person limit, get there early, no speaking, no cell phones—encourages viewers to pay attention in a way they normally would not, or could not. When a painting is hanging on a wall, and one can either stand in front of it for two hours or walk by it in a second, most people walk by it in a second. Maybe, if we’re lucky, they’ll pause for a full minute or two, but it is rare. There is something phenomenal about being allowed (made to spend?) ten full minutes—no more, no less—to look. A lot can happen in ten minutes.

PSAD was, above all, a lullaby; a soothing respite in the middle of the chaotic hustle and bustle of New York City; a quiet desert at the center of a downpour. Was it worth all the effort to get ten short minutes in heaven? You bet.

Sara Estes is a writer and editor living in Nashville. Her writing has been featured in The Los Angeles Review, The Bitter Southerner, Hyperallergic, Oxford American, BookPage, Filling Station, Number, Chapter 16, Empty Mirror, The Tennessean, Nashville Scene, and more

A Hush in the Hustle: Doug Wheeler at the Guggenheim

Related Stories

Reviews

Features

Reviews

As for me, I’m just passing through this planet at Bad Water, Knoxville

Harrison Wayne reviews the entangled sculptures and taxidermic specimens found in As for me, I’m just passing through this planet at Bad Water, Knoxville.

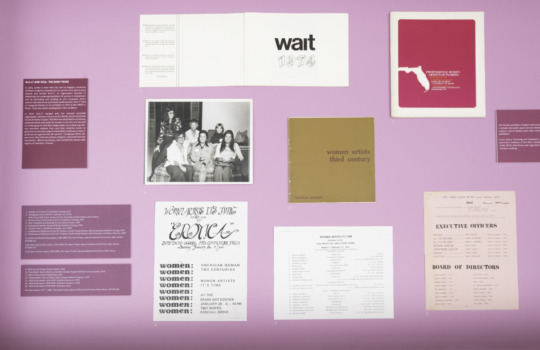

Women’s Voices: A Journey Through Miami’s Art History at Miami-Dade Public Library Central Branch, Miami

Carolina Ana Drake highlights the local legacies of Miami women artists in Women's Voices: A Journey Through Miami's Art History at Miami-Dade Public Library Central Branch, Miami.

Everyday Love by Richard Dial at Institute 193, Lexington

Daniel Fuller reviews the crafted metal chairs reflecting tenderness and the human condition in Everyday Love by Richard Dial at Institute 193, Lexington.