In organizing the exhibition “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art,” currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg, curator E. Carmen Ramos asked herself the rhetorical question, “What is Latino about American art?” It’s the same question she has asked since 2010, when she joined the staff of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and began expanding its Latino holdings. Drawn from SAAM’s collection, “Our America” features 75 artworks by 62 artists in a variety of mediums, including painting, sculpture, installation, photography, and video.

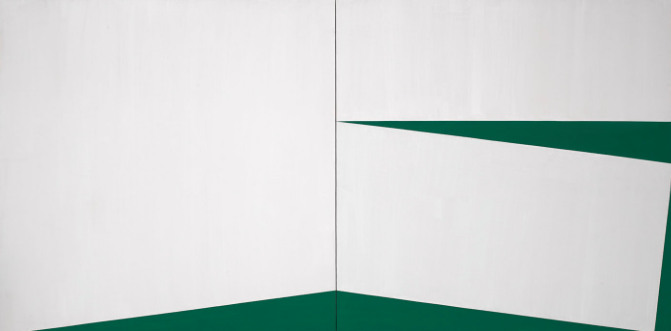

Ramos selected Carmen Herrera to represent a category of Latino artists who came to the United States in the mid 20th century, enrolled in American art schools, and became a part of the American art scene. The canvas Blanco y Verde (1960) demonstrates Herrera’s deep interest in the interplay and tension between form and color. A native of Cuba (b. 1915), she took art lessons as a child, and in 1938-39 studied architecture at the Universidad de La Habana, an experience that provided the roots for her interest in form and structure, which is so strongly evident in her paintings. Herrera studied at the Art Students League in New York City in 1942 and ’43. In 1948, while living in Paris, she became friends with and exhibited alongside such artists as Barnett Newman and Ellsworth Kelly. Herrera settled in New York City in 1954, and continues to live and work there. Now at 101 years old, she is the subject of an impressive solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. She shares with many American female artists the reality of having been marginalized for most of her life; she was 89 years old when she first sold a painting.

Like Herrera, Olga Albizu (b. 1924, Puerto Rico; d. 2005, New York City) embraced the new American avant-garde of the mid 20th century. To create her painting, Radiante, she used a palette knife to apply impasto blocks of yellow, orange, and black pigment to the vibrant yellow background. The intensity of these colors work together to generate a mood. Albizu’s studies reflect the time of change in American art, as the Abstract Expressionists helped New York surpass Paris as the global capital of the art world. Before Albizu came to New York, she studied in her native Puerto Rico with Spanish artist Esteban Vicente, earning a scholarship to study with Hans Hoffman at the Art Students League in New York City in 1948. She also spent time in Paris and Florence before settling in New York in 1953. By 1956, she had carved out a uniquely North American niche for herself by getting her paintings on the covers of jazz records produced by RCA and Verve, most notably for musicians Stan Goetz and João Gilberto.

“Our America” also includes pieces from artists of Latino descent born in the United States and trained in American art schools during the 1960s, when art students were encouraged to explore non-traditional art forms and were beginning to use their art to make social statements. Raphael Montañez Ortiz (b.1934, Brooklyn) has a vastly complex heritage that includes an indigenous Yaqui great-grandmother. He attended the High School of Art and Design in New York City, and he went on to get his BFA and MFA from Pratt Institute and a doctorate in fine arts and fine arts education at the Teachers College of Columbia University.

Ortiz’s work Cowboy and “Indian” Film (1957-58) presages what was to become his longstanding interest in deconstruction. To make this film, he took several copies of Anthony Mann’s film Winchester 73 (1950), chopped them up ceremoniously with a tomahawk, tossed the pieces around in a medicine bag, and then pieced together the scraps to create his own video. In his reconstructed film, some of the segments are upside down, and the action sometimes moves backward. His intent was to encourage the viewer to think about how Native Americans are depicted in the media.

Those of us who grew up in the 1960s found ourselves living in a politically charged era. “Our America” includes Latino artists confronted many of these issues right in their own backyards and found that their artistic voices were their best tools for speaking out. Ester Hernández is a first generation Chicana artist (b. 1944, Dinuba, California) and daughter of workers who had migrated to California from Mexico to work in the commercial grape vineyards. She took up the cause of publicizing widespread unhealthy growing conditions and horrible labor practices. For her most famous protest poster she used the Sun-Maid Raisins brand image of the young woman in a bonnet holding a basket of grapes. She altered the text to read “Sun Mad” and added the line, “unnaturally grown with insecticides, miticides, herbicides, and fungicides”; the lovely young maid in the original image is replaced with a skeleton.

The wonderful irony to this story is that in 1988 the raisin company gave the original red bonnet used to create the Sun-Maid image to the Smithsonian, where it is on display next to Dorothy’s red slippers from the Wizard of Oz. When Hernandez created her protest poster, it did not receive much attention, but as her reputation as an artist has grown, so has awareness of the poster, and now it too is in the Smithsonian collection and is part of this show.

Numerous artists featured in this exhibition deal with the theme of migration and the psychological repercussions of separation and loss that come with leaving one’s homeland, re-settling in a new environment, and making a new beginning. Christina Fernandez (b. 1965, Los Angeles) created Maria’s Great Expedition (1995-96) by interviewing relatives and studying American and Mexican history. It is the saga of the artist’s great-grandmother, who was the first member of the family to leave Mexico for the United States.

The photo installation includes seven photo prints and a bilingual narrative. One of the prints is a map that chronicles Maria’s travels through several states in the American Southwest, mimicking displays in history museums that show the treks of early explorers. The timeframe for this journey is 1910 to 1950, and the narrative intertwines a personal story with a description of events that took place in America during this 40-year period. Embedded in the subtext is the message that all histories express individual experience, preconceived ideas, and sociopolitical biases and that they could not be otherwise because the person writing the history brings their own ideas to the script. The first two clues that reveal this subtext are that the artist has photographed herself in the guise of her great-grandmother and that she does not age over this 40-year period. Fernandez has inserted artifacts from present times into what are supposed to be historical images, including a fanny pack, a ninety-nine cent sale flyer, and a 21st-century automobile (in the frame Transporting Produce 1930 Phoenix, Arizona.) The series of images and the accompanying text meaningfully recount the story of a person of character who undertook a bold and difficult journey to better her life and whose decisions clearly had a positive impact on future generations of her family.

Other artists in the show feature everyday people as a way to communicate about the issues of being Latino or Latina in America and to offer alternatives to the stereotypical images in the media. To counter the portrayals of Puerto Ricans as criminals and gang members in West Side Story (1961) and Fort Apache, The Bronx (1981), Sophie Rivera (b. 1938, New York City) decided to photograph her fellow neighbors of Puerto Rican descent to convey their humanity and character. She took an unusual approach to finding her subjects; she would stand outside her building and approach people as they passed by, asking if they were Puerto Rican and, if so, would they be willing to be photographed. She produced 50 black-and-white photographs, but only 14 survived a fire in her studio. Her subjects appear relaxed and look straight at the camera. Though they remain anonymous, Rivera managed to portray a genuine connection to these individuals.

Emilio Sanchez (b. 1921, Carmagüey, Cuba) relocated to New York City in the 1940s, but it took him until the 1980s to begin depicting Latino neighborhoods in his adopted city and interpreting their impact on the urban landscape. La Rumba Supermarket references the popular Cuban dance of the same name. The vibrant colors of the market are reflective of the colors found all over the Caribbean, and the awning—announcing helados (ice cream), fruitas (fruits), and dulces (sweets)—is meant to entice.

The United States always has been and hopefully always will be a nation of immigrants, and those who come to our shores will continue to have the positive experiences that have been expressed by the artists in this exhibition. Artists speak for themselves, and for society, and thus for all of us. “Our America” is a far-reaching and comprehensive exhibition that shows us in a variety of artistic styles and mediums what it is like to become and to be an American.

“Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art” remains on view at the Museum of Fine Arts St. Petersburg through January 27, 2017. It will appear at the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga, February 17 – June 4. Since its 2013 debut at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, “Our America” has traveled to the Frost Art Museum at Florida International University in Miami, the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City, the Arkansas Art Center in Little Rock, the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington, and the Allentown Art Museum in Pennsylvania.

Ann Gurley Rogers is a freelance writer and independent curator living in St. Petersburg, Florida. She has been writing about the arts since the mid-1990s.