I was suspicious at first. Taxidermy has become so trendy that it’s been satirized on the TV show Portlandia, where this past season the conflagration of the Dead Pets store led to a dramatic trial of the weirdo characters. Apparently the trend even has a name: rogue taxidermy. Artist Kate Clark was included in Robert Marbury’s 2014 book on the subject, Taxidermy Art. But in Clark’s show at Newcomb Art Museum, the trend works.

Clark’s sculptures combine taxidermied animal hides with sculpted human heads to create the illusion of a hybrid animal-human creature. The result is a startling success, and immediately discerned in the three antelopes of Ceremony (2011) placed in the center of the main gallery, their quizzical human faces turned toward the viewer. Their long, goat-like ears made me think of Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. I was transported to a theatrical space of dreams, a place where fantasies can become real.

Before being covered with repurposed animal hides, the bodies are built up out of foam and clay. The gallery lights glimmer off their rubber eyes and the gold nails that hold together the various hide pieces covering the faces in a patchwork pattern. The use of taxidermy connects the sculptures to natural history museum dioramas, but the installation choices here smartly sidestep that association. The dark colors of the hides and furs seem to float against the white walls and the white pedestals, as in Fortitude (2011), where two bears ride a pile of white-painted wood chips. The result is the best that the white cube can offer: a dreamlike space separated from the strictures of our everyday world. Gallant (2015), an antelope hide with the white spots characteristic of a deer, hangs from the ceiling, its feet tucked in mid-run, casting shadows on the white platform below. In Bully (2010), a submissive wolf figure returns the gaze of the dominant wolf-figure looking down on him from the height of another pile of white wood chips. The bully in question, though, does not look mean—his human face looks more protective than threatening. Their back legs and tails are intertwined, creating a couple.

In looking at the more humane treatment of the theme in Bully, I could feel the instinctual wish, “if only I could avoid bullies.” We use the dominance-submission dynamic of animal relationships as a model for understanding the bully dynamic in human ones, but we’ll never know what it’s really like to live an animal life. Clark’s hybrid creatures point to the psychological projection at work when we imagine that animals share our own human feelings. And her poetic titles capture this projection, expressing how we use animals as wish-fulfillment dreamcatchers. My heart beats like thunder (2012) is a cougar, sitting propped up on its front legs like a regal cat, its tail circling around it on the pedestal. Looking at it, I think, “if only I could get what I want as easily as a cougar catches its prey.”

The texture of the fur and the hides is crucial; you will want to touch them. Sculpture has always had to deal with the fact that one of its essential elements—the texture of different materials—is conveyed optically rather than experienced through touch. To touch these creatures would destroy their illusion and reveal the banal source of their magic in dead animal hides. What keeps them alive for our imagination is not being able to touch them. It’s that split second when your brain kicks in and holds back your hand, when you remind yourself that touching is not allowed in this space. Yet, you imagine it. You know from past experience, from childhood trips to petting zoos, what that hair will feel like. What makes them so successful as sculpture is the way they play with the proscription against touch within the white cube.

Clark’s work is paired with Andrea Dezsö, another artist who creates flights of fantasy to inspire the viewer. Her touchstones are classic fairy tales, combining their thematic darkness with a whimsical 2-D graphic sensibility. On view are black and white ink on paper drawings done as illustrations for The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm (Princeton University Press, 2014). It is the combination of innocence and violence that makes these stories work, and Dezsö is clearly part of the anti-Disney trend to rescue the original darkness of these tales that Disney intentionally omitted.

Subversion is a thread running throughout the work, especially in her relationship to craft traditions. The “Sketchbook Plates” are dishes that recall 18th century Dutch blue and white Delft earthenware, their domestic associations subverted by subject matter that doesn’t fit the tradition. The nostalgic vibe of that 19th century farmhouse contrasts with the 1920s modernism of the factory emblazoned on the dish The Smell of Chamomiles at Night (2009). Opposite the plates is an embroidery series in shadowbox format, each piece recalling the sampler tradition, but starting with phrases, such as, “My mother claimed that…Hepatitis is a liver disease you get from eating food you find disgusting,” and “Men have stinky feet,” and “If you inhale the scent of lilies while you sleep you can die.”

In a nice disparity to Clark’s sculptural work, Dezsö’s sensibility is 2-D, using figure/ground contrasts. These images become three-dimensional in a planar approach by using the tunnel book format, an 18th and 19th century tradition in which the viewer gazes on a tableau through a hole in the cover of the book. The ‘pages,’ so to speak, are not flipped through, but instead seen all at once in successive cut-out layers, separated by accordion fold seams on both sides to create a deep stage-like space (see an 18th century example here). Several small ones, each about six inches high, are on view, such as Gentle Beast Hiding Behind Molten Lava (2009). Two larger ones, about 14 inches high, are entirely white and made of Japanese hand-made Shojoshi paper. Forest Stroll with Goat (2014) features a small girl and her goat walking through a forest haunted by a hairy devilish creature with horns, reminiscent of Little Red Riding Hood. Bat Cave (2015) features the same girl, a bat alighting on her outstretched hand while another devilish figure above her plays a recorder.

For the Tulane show, Dezsö scaled up the tunnel book project to make a site-specific installation of two scenes, Krewe of Intergalactic Women Travelers Reach a Cave in Outer Space (2016). Instead of the all-white approach, the planes are black with four cut layers moving from a deep purple to magenta to peach, colors created by theatrical gels aimed at the laser cut Bristol paper planes. It feels like we are looking through a stage set, and moving from side to side changes the point of view to reveal new slices of the layers. Vegetation is cut into the edges of each plane, arching over the center. Hybrid creatures with beaks and lacy headdresses navigate through the new world, walking in pairs or groups amongst the umbrella-like trees that bend down in graceful arcs. Some have wings like dragonflies, or bee-like heads, but clearly human legs and hands. They are funny, and they are cute, but this world doesn’t seem obviously connected to the outer space mentioned in the title.

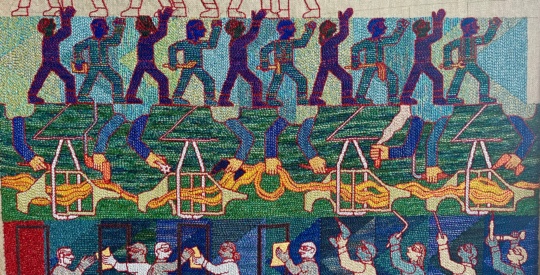

The title uses the term ‘krewe’ that any local would know to connect to Mardi Gras, where each parade is sponsored by a krewe of members. Dezsö’s krewe was inspired by drawings from an 1892 parade sponsored by the Krewe of Proteus, found in the Louisiana Research Collection at the Tulane Library. The drawings are on view in the gallery alongside the installation, and they steal the show from Dezsö’s installation. Instead of depicting obvious floats, Carlotta Bonnecaze’s watercolors stage the space of the parade’s theme, “A Dream of the Vegetable Kingdom.” The krewe members have shrunk to the size of little dolls, like the family of Mary Norton’s classic children’s book The Borrowers.

Dezsö shared with me that she was inspired by the local habit of taking play seriously, of imagining other worlds and then building them, making them real. Across town from the gallery at the Tulane City Center, Dezsö installed a Mardi Gras parade in matte gold vinyl on the building’s sidewalk windows. The ambiguous silhouettes could be hybrid creatures or they could be New Orleanians in costume, masking for Mardi Gras Day. It’s true that New Orleans understands this kind of play, as well as its potential for subversion. But I prefer the illusion of the 1892 drawings to Dezsö flattened creatures. Clark’s sculptures maintain more of an edge to the line between fantasy and reality, an edge that gets at the true heart of Mardi Gras. It is not a cut-out heart, or an abject anatomical one. Its power is always in between pure fantasy and abject reality.

“Andrea Dezsö: I Wonder” and “Kate Clark: Mysterious Presence” are both on view until April 10 at Newcomb Art Museum at Tulane University.

Rebecca Lee Reynolds is an assistant professor in the department of fine arts at the University of New Orleans, where she teaches art history.