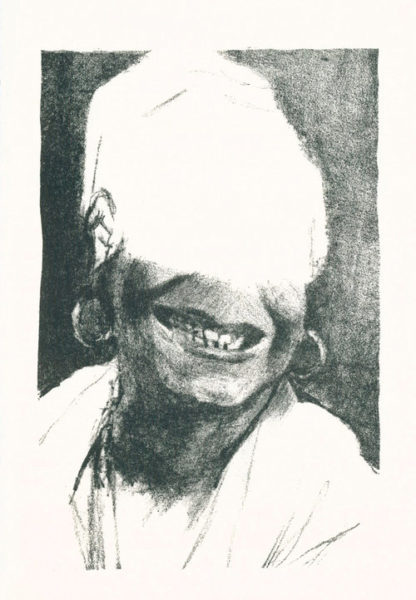

Currently on view at Little Rock’s Historic Arkansas Museum, “That Survival Apparatus,” an exhibition by emerging artist Justin Tyler Bryant featuring enigmatic portraits of African American luminaries, spans the media of lithography, book arts, and painting. Through the artist’s delicate grayscale renderings of his subjects’ mouths, cheeks, and jawlines—and the complete erasure or absence of the remaining facial features—the images depicted by the twelve lithographs on view hover between significations of there and not-there, known and unknowable, beloved and effaced. This presentation leaves the figures’ expressions unreadable: the mouths are clearly and tenderly etched but are enclosed by a void. The bodies are achromatic expanses.

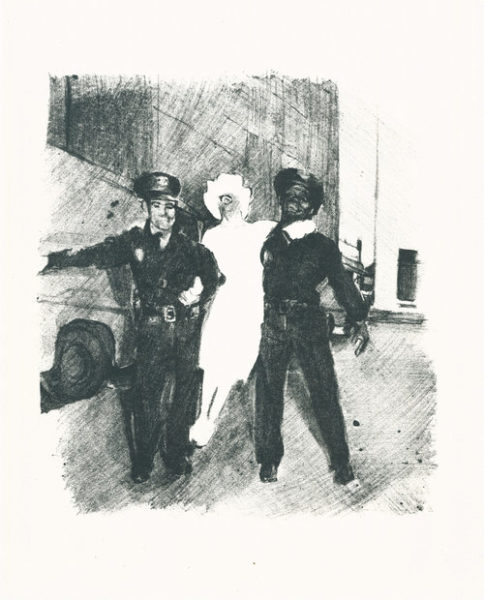

The image in the lithograph Ah Ha shows a woman’s mouth agape and embedded in the mere outline of a body. Her head is thrust back, possibly from the impact of being forced forward by the two police officers that bookend her person, or from the strain of a burgeoning cry. The officers—one white, the other black—have easy, boastful smiles, and their figures are fully drawn. The female figure’s feet are lifted away from the ground; the outline of her head is diaphanous like a poppy, her legs are swung to the side like a pendulum, and the gestural weight of her body sways between the registers of ebullient dance and captive horror.

The surrounding ethereal prints depicting Maya Angelou, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, members of the Niagara Movement, and a coterie of civil rights leaders are intimately presented, salon-style on a single wall like family portraits. According to the artist, Angelou’s poem “The Mask” provided a framework for Bryant’s show. Building on Paul Lawrence Dunbar’s earlier poem “We Wear the Masks,” Angelou’s “The Mask” imagines the interior voice of an aged black domestic worker who is forced by circumstances to smile or laugh in the face of discrimination and abuse. She writes, in part,

Seventy years in these folks’ world

The child I works for calls me girl

I say “HA! HA! HA! Yes ma’am!”

For workin’s sake

I’m too proud to bend and

Too poor to break

So…I laugh! Until my stomach ache

When I think about myself.

For Bryant, “The Mask” isn’t just a metaphor for marginalized people doing what is necessary to survive: performing the roles put upon them by racist and sexist social strictures. It also represents an evolving methodology of cultural resilience constituted by strategies such as hidden transcripts and code-switching.

In Zora, the mouth and front teeth of novelist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston are clearly drawn, as are the spheres comprising her necklace, but the rest of the author’s visage is blank. At first glance, the blanched negative spaces seem to recede then pulse forward, as in a high-relief sculpture. The eye doesn’t quite know what to do with that emptiness. In another portrait, Rosa Parks’s beatific smile is framed by the mountainous line of her collar below and the thin suggestion of a nose above. The rest of her face is eggshell and blank, leading the eye again to search for information.

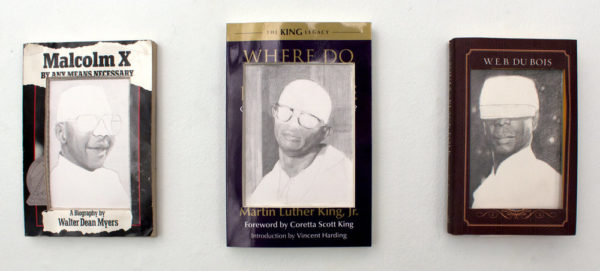

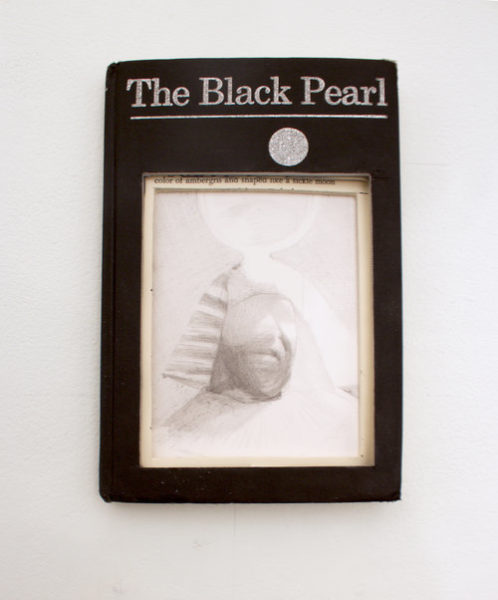

In an installation called Black Radical Nerd, the altered covers of books by Martin Luther King, Jr. and W.E.B. Du Bois frame portraits of figures such as the character Steve Urkel from the 90s sitcom Family Matters and comedian Damon Wayans. Bryant’s presentation of partial portraits within the archival context suggested by these books and the museum more broadly serves as a comment on the erasure of nonwhite perspectives in historical narratives. The book installation shares space with the diptych Ascension, in which images of faces torn from magazines are recreated in delicate washes of watercolor. The visual depth of the watercolors and fissures of torn paper makes the painting almost appear like a cracked fresco.

In the work on view in “That Survival Apparatus,” Bryant suggests that the partial stories provided by history have not only robbed the present of broad cultural inheritances but also of memories of individuals’ idiosyncrasies and particularities. Through such gestures as wryly depicting the facial features of Urkel within the cover of Malcolm X’s biography, Bryant teasingly reminds viewers that received notions are almost always oversimplifications, caricatures stripped of life’s complexity. This is as true of the false monolith of “black people” as it is of individual figures like Malcolm X.

In the face of our partial histories, biased impressions, and personal prejudices, how can truth and a direction forward be discerned? Bryant’s work suggests that one way is by learning to pay attention to the details as well as the absences. In his 2015 book Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates describes finding a redemptive truth in the indelible specificity of the people of his community. He said his truth was “made of small hard things—aunts and uncles, smoke breaks after sex, girls on stoops drinking from mason jars. These truths carried the black body beyond slogans and gave it color and texture.”

Justin Tyler Bryant’s “That Survival Apparatus” remains on view at the Historic Arkansas Museum in Little Rock through Oct. 7.