In a 1973 letter to Swiss curator Jean-Christophe Ammann, Gerhard Richter explained the potential for contemporary artists to paint like Casper David Friedrich. He wrote that it is “not a thing of the past. What is past is only the set of circumstances that allowed it to be painted … if it is any ‘good,’ it concerns us—transcending ideology—as art that we consider worth the trouble of defending.”(1) This way of framing the relevance or importance of making a work of art is similar to the conceptual development of the newest exhibition, “WHITE,” open through April 26 at the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Jacksonville, Florida.

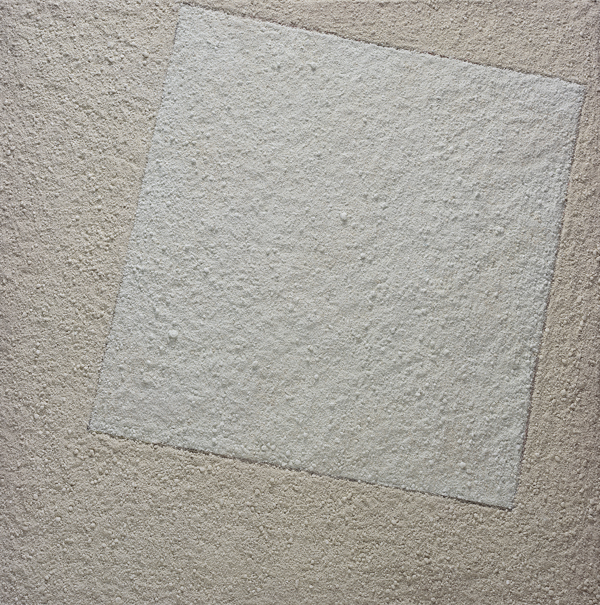

Instead of a Friedrich painting, this exhibition is predicated by the canonical 1918 painting White on White by Kazimir Malevich. And, though this work is not included in the exhibition, as Richter implies, it is quite possible to construct an exhibition that is “like” this composition. By selecting works that have been developed within the past 50 years, including a work by James Nares that was painted specifically for this exhibition, “WHITE,” contextualizes a variety of artists, processes (including types of representation or abstraction), materials, and even concepts in an exhibition that, without the signifier of color, identifies itself through comparative analogies described in the wall labels. The artists presented are: Tara Donovan, Ann Hamilton, Les Levine, James Nares, Kenneth Noland, Jules Olitski, Robert Rauschenberg, Bill Viola, Rachel Whiteread, and Vik Muniz, whose photograph, Suprematist Composition: White on White, after Kazimir Malevich (Pictures of Pigment), 2007, an appropriated composition of dry pigments, serves as the understudy for the exhibition’s lineage.

Opening one-week prior, the exhibition, “Black/White,” at J. Johnson Gallery in Jacksonville Beach was planned to coincide with MOCA’s program, and indicates further the intention of investigating achromatic modern and contemporary works. J. Johnson’s opening reception served as a benefit, with ticket sales going to support MOCA, the private, nonprofit, educational, and cultural resource of the University of North Florida.

The works featured (through March 13) at the commercial gallery J. Johnson are, of course, available for purchase. The artists include Polly Apfelbaum, Donald Baechler, Paul Boneau, James Brown, Francesco Clemente, George Condo, Jessica Drenk, Qin Feng, April Gornik, Robert Greene, Alfred Leslie, Sol LeWitt, Georgia Marsh, James Nares, Louise Nevelson, Mark Sheinkman, Pat Steir, and Donald Sultan.

The exhibitions share commonalities in their democratic efforts to present a range of work, from heroic gestural monochromes to understated imagery, from works with palatable physicality to those with intimate meditations. Only one artist, James Nares, is featured in both exhibitions, but all artists’ works seem to be presented independently, intended to be viewed individually, yet united by their lack of color.

There is one work in the black and white J. Johnson show that is an anomaly, Pat Steir’s Wolf Waterfall (2001), a two-color screen-print with silver cascading over the deep black of the negative space. While most of the artists have multiple works on view, this is the only one by Steir, and the only work that presents a subtle yet refreshing and distinguishing splash of silver.

Arthur Goldberg Collection.

If the artists included were performing a chorus, their works would function as harmonies. Shifts in scale, media substitutions, and drawn and printed surfaces act as alternative explorations to re-engage a subject, conjure an emotional counterpart, or test new directions in the artists’ practices.

The works included in the MOCA exhibition seem positioned to confront or engage the viewer, and some are reserved for more intimate encounters. Specifically, by being cornered in a private room , the hypnotic images in Bill Viola’s 1979 video Chott el-Djerid (A Portrait in Light and Heat), present an alternate fiction. Also, a smaller room that contains a selection of Rachel Whiteread’s cast boxes, Ann Hamilton’s installation Still Life (1988/1991), and Les Levine’s canvas-wrapped David’s Choice (1963), has a regulated entry to protect the works. The museum’s intention in managing this space is to create a more personal experience. The solemnity of Hamilton and Whiteread’s works can be felt, but could be more cogent in individual spaces.

The original presentation of Ann Hamilton’s Still Life involved a performative installation with a lone sentinel seated at a table of covered with 800 folded, singed, and gilded work shirts. Now, the chair is vacant. Where the work was once a commentary on the corruption of servitude, the absence now seems more indicative of joblessness and the inequitable distribution of wealth. Do the shirts need a steward for protection, or will they be outsourced?

Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York.

In Tara Donovan’s installation, Haze (2013), the repetitious placement of mass-produced translucent straws, carefully undulating in a vertical excessive landscape, is also an accumulation of stacked objects. Where Hamilton’s work intends to remain still and vacant, Donovan’s attempts to conjure an unnatural atmosphere where visual apparitions appear to tremor and shape-shift, creating a feeling of uncertainty and imbalance.

For Rachel Whiteread’s cast works, unadorned reliquaries of absent space, the quietude of their presentation professes their humility. Contrasting in presence, Rauschenberg’s large prints from the Spartan Series, composed of layers of white imagery, seem to expunge the picture plane. The results are sobering collections of ghostly afterimages.

These two exhibitions present to their viewers the timeless relationship of art making to color; however, they are not as relational as David Batchelor’s Found Monochrome series; as bold (yet circumstantial) as Thelma Golden’s “What’s White…?” from the 1993 Whitney Biennial catalogue; as poignantly considerate as the narrative of colonialism, racism, and imperialism in Heart of Darkness; or as hip as Michael Jackson’s Black or White. According to Batchelor in his book Chromophobia, color is inextricably bound to Western culture, and that attempts to purge color from culture is a form of denial. What, if anything, do these exhibitions deny? Batchelor also asserts that color and white are not opposites, yet by isolating the austerity and purity of white, color is determined to be “intoxicating, narcotic or orgasmic, colour is learned, ordered, subordinated and tamed. Broken.”(2)

Accordingly, the works on view at MOCA are formal, earnest, and whole, and J. Johnson Gallery affirms this with approachable works that aim to have broad appeal. The museum promises that the next Project Atrium show, Angela Glajcar’s all-paper installation, will be an extension of the “WHITE” show. Her work will be on view March 28-June 28.

1. Gerhard Richter, Letter to Jean-Christophe Ammann, February 1973, in Gerhard Richter, The Daily Practice of Painting: Writings and Interview 1962 – 1993, ed. Hans-Ulrich Obrist. Trans. David Britt (London: Thames & Hudson, 1995), p. 81.

2. David Batchelor, Chromophobia, Reaktion Books Ltd: London, UK, 2000, p. 49.

“WHITE” is on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville through April 26. “Black/White,” at J. Johnson Gallery in Jacksonville Beach, can be seen through March 13.

Lily Kuonen is an assistant professor of art at Jacksonville University in Florida. She is a native of Arkansas, where she was born in the kitchen of her parents’ house.