You’d think that exhibiting Carrie Mae Weems’s Sea Islands Series at a museum located in the sea islands is a no-brainer. It’s the sort of thing that makes you stop and ask, Why hasn’t this been done before? Weems’s series of black-and-white photographs was produced in 1991-92 and went on tour in 1994-95, making stops in the South at Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and Columbia, South Carolina. But this exhibition at the Telfair Museums in Savannah is the first time since then that the series has been reunited, and the first time it has been shown near the islands where the photographs were made.

Since the 1990s, Weems has won a MacArthur “genius grant,” been the subject of a retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum (unbelievably, its first solo show by an African-American woman), and explored the intersection of race and violence in works like Lincoln, Lonnie, and Me (included in Prospect.3 in New Orleans in 2014) and the performance “Grace Notes: Reflections for Now” (in Charleston for the Spoleto Festival in 2016; you can read my review of it here). The Sea Islands Series exhibition feels like a homecoming, as well as an opportunity to reconsider its meaning in a new political context.

The Sea Islands Series focuses on the Gullah-Geechee culture in the barrier islands of South Carolina and Georgia. The terms Gullah and Geechee refer to African-American communities descended from the slaves that worked the plantations on these islands in the 18th and 19th centuries (Geechee comes from the Ogeechee River, and is used to refer to the Gullah people living around the river just south of Savannah). Their geographic isolation on islands stretching from northern Florida to North Carolina meant that they preserved African traditions that disappeared on the mainland. The Penn Center on St. Helena Island has long operated as the center of Gullah culture, and has been active in not just preservation but also social justice movements. In 2006, the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor was created to protect sites associated with the culture and bring greater attention to it.

Weems’s series was part of a renaissance of the Gullah-Geechee culture in the ’90s—a moment when a culture that had been considered backward was reclaimed and newly appreciated. Director Julie Dash’s film Daughters of the Dust came out in 1991, and it was set in the same communities on the barrier islands, but circa 1902. Kerry James Marshall was her production designer. The film has been rediscovered by a new generation, thanks to Beyoncé. The costumes and look of Daughters of the Dust clearly influenced the video for Beyoncé’s Lemonade, which features a group of women in white Victorian-style dresses. The matrilineal power of the community in Beyoncé’s world is integral to Dash’s film, which explores one black family’s decision to leave the islands and pursue greater opportunities up north.

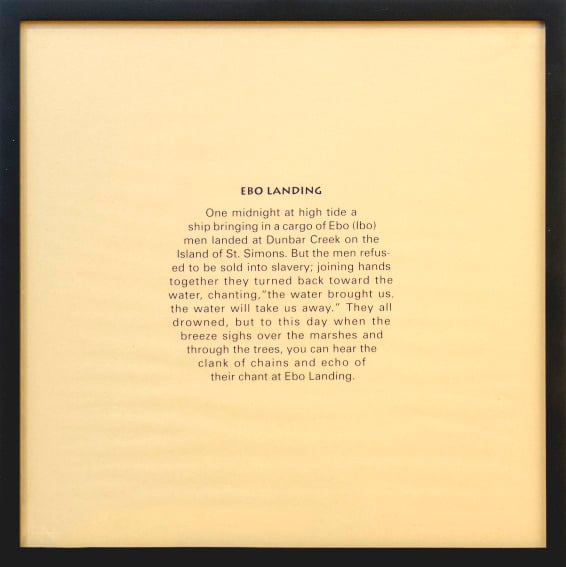

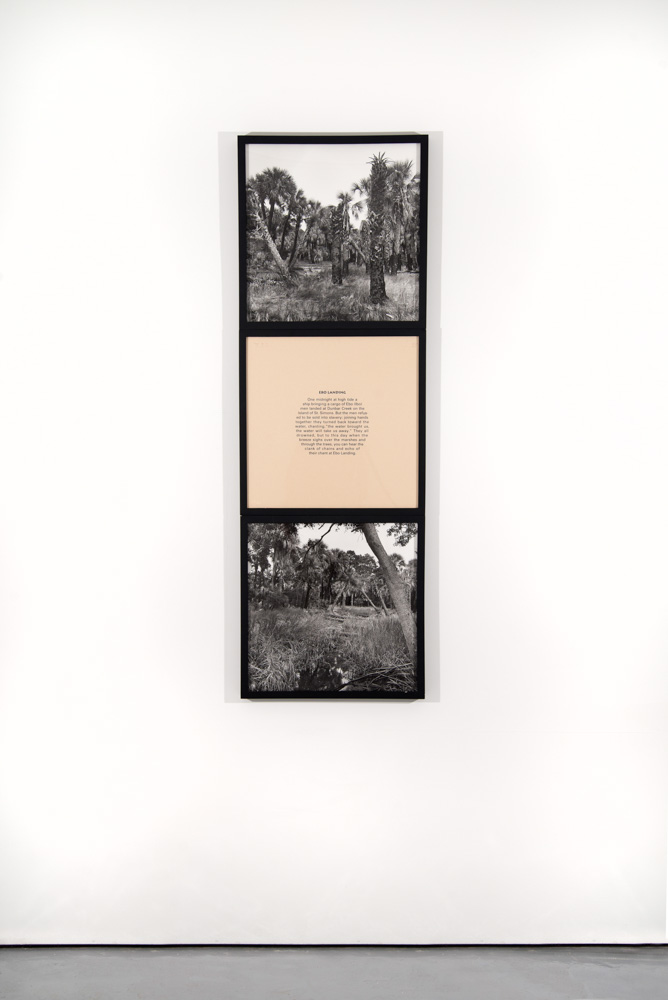

Dash set her film on Ebo Landing—not an actual barrier island, but a reference to a story about a mass suicide in 1803. When the Ebo/Ibo peoples from Nigeria were brought to St. Simons Island to be sold into slavery, they resisted by walking into the sea they had just crossed and drowning themselves. Weems references the same story in a triptych in the Sea Islands Series, with photographs of palmetto tree-laced landscapes. The text in the central panel recounts the story and ends, “They all drowned, but to this day when the breeze sighs over the marshes and through the trees, you can hear the clank of chains and echo of their chant at Ebo Landing.” This tension between a silent landscape image and memories of violence and resistance is key to the series as a whole.

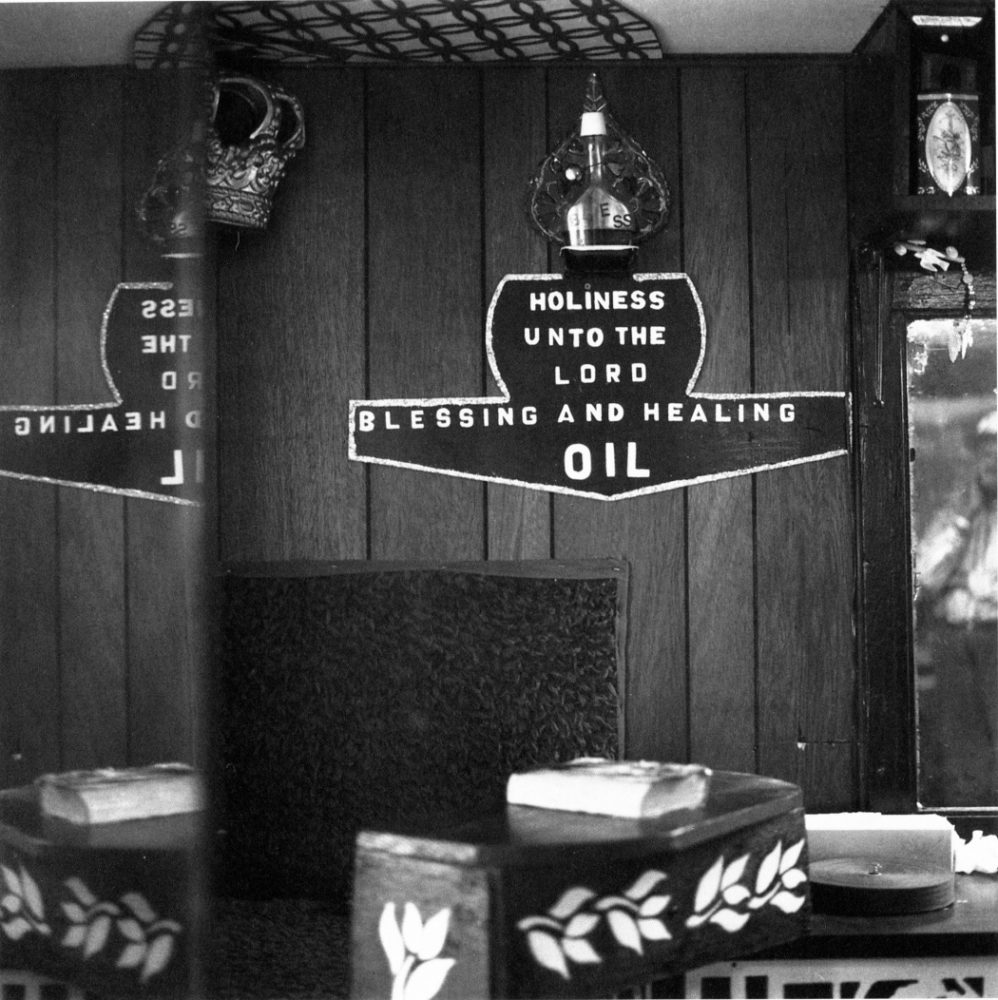

Weems learned about the Gullah-Geechee culture while studying for a master’s degree in African-American folklore at the University of California, Berkeley. The images were really a research project, for which Weems traveled from the West Coast to see the place she had learned about in the classroom. Like a scientist looking for evidence, she shows us bottle trees and hubcaps in trees and other practices that the dominant culture would consider superstition—or voodoo. A box spring from an old bed seems to float in the trees in one image, its pattern of circles recalling decorative ironwork. While the formal elements are intriguing, the box spring had a use, like a bottle tree, to catch spirits. These images are paired with text panels that outline the specific beliefs of the Gullah Geechee. A panel titled Birthing and Babies, for instance, lists 14 different beliefs on the topic, beginning with “If you dream of fish, somebody you know is pregnant.”

Though some of Weems’s images may seem documentary, others are clearly staged. In one diptych, we see a bedroom with evidence of its inhabitant: a fedora hat resting on the bed’s coverlet, snakeskin shoes peeking out from under the mattress. In another, a female figure is Weems herself—positioning herself in the narrative is a trope that she would redeploy in later series, such as the The Louisiana Project (2003). The second panel shows an empty chair and a bowl of water on the floor—a reference explained by the accompanying text which includes instructions to put out a pan of water to protect oneself from bad karma brought inside by visitors. Throwing out the water then gets rid of the bad karma.

The Gullah Geechee are known for a specific language, long thought to be a dialect of English, but actually a combination of English and about 31 different African languages. Weems often uses text in her work and specifically engages oral culture. Panels in this series list the Gullah terms by connecting them to their African sources and the English equivalent, such as the derivation of the Gullah Geechee names: “Gola/Angola/Gulla/Gullah/Geechee.” The words are paired with images of storefronts in Savannah, their hand-lettered signs advertising food and laundry services. A hand-painted peanut above the window of one store connects the image to its neighboring panel, which reads “Mpinda/Nguba/Goobers/Peanuts.”

The spaces of both Weems’s series and Dash’s film are very real, and many still exist today, but the artists treat them as symbolic spaces. Dash does not use the name of a real island in her film, and Weems does not title the photographs with actual locations. The image of a grove of trees dripping with Spanish moss could have been taken almost anywhere in the islands. As someone who grew up going to one of these barrier islands, it’s tempting to try to figure out where these places are. In fact, I felt a thrill of victory when I recognized the slave cabins in an image of Boone Hall Plantation, located outside Charleston. Boone Hall is very popular with Charleston tourists today, as well as with brides (Ryan Reynolds and Blake Lively got married there), but it is also a very strange place. Its white-columned plantation house was built in the 1930s to imitate Tara in Gone with the Wind and appeal to a burgeoning tourist audience that expected to see the myth of the South and not its reality. But the authentic brick slave cabins right next to the ‘fake’ house threaten to disrupt the fantasy traditionally offered by hoop-skirted tour guides.

A vitrine in the center of the gallery shows a collection of dinner plates bearing text. Each one begins “Went looking for Africa” and then reports to have found it in unexpected places: “and found Africa/in a wrought iron gate/the design of/the master house/in the shape of a/sweet-grass basket/in a round/smoke house.” That round smoke house is visible in the Boone Hall images, and sweetgrass baskets are a prized local craft tradition in Charleston. Another plate reads “Went looking for Africa/and found/carpetbaggers ready to take/Daufuskie/den took/Hilton Head/run off/Sapelo.” Likely everyone will understand the carpetbagger reference to Reconstruction, which Weems connects to the gentrification of Hilton Head and Daufuskie islands. Sapelo may have resisted at the time, but recent reports highlight new waves of development there. Hilton Head is the location of the cemetery images in Weems’s series, but no tourist staying there today would recognize it, as the island is dominated by golf courses, condos and vacation homes.

What is not seen in the photographs is exactly what’s so important about these locations. This absence brings up the question of how gentrification has pushed out native residents and threatened to make the Gullah Geechee culture extinct. It’s what has led one group to work to preserve Ebo Landing and save it from development. It is the tension that Pat Conroy writes about in The Water is Wide, his 1972 memoir of working as a schoolteacher on Daufuskie Island in 1968. Daufuskie, too, is now a resort. And it is the tension that drives Dash’s film. “Recollect” is a key word repeated over and over as the characters prepare to leave the island and yet are afraid of losing their connection to the land, to the Gullah Geechee culture, and to their sense of identity.

Weems’s images function as recollection. The diptych of a “praise house,” for instance, remembers the small houses of worship built on plantations during slavery, and how these spaces testify to a tradition of celebrating life and faith, even in the face of bondage and violence. The gallery is a jewel box of places as memories, but it’s like deciding to keep all of your family mementos in a box, only to have your grandkids ask, what’s all this junk? Thus the curatorial decision to add didactic panels throughout the series that explain the referents of Weems’s images. Next to the praise house image is a panel titled “Religion.” It explains how, in order to continue African traditions, slaves adapted the Christian practices imposed on them. A quote from Southern historian Charles Joyner explains the theory and the details, discussing trances and spirit possession and the importance of the “shout” as a version of the West African ring dance. This approach runs the risk of turning the artworks into a history lesson, but the curator sidestepped that risk with oral history interviews that focus on contemporary Gullah culture. The Religion panel features a quote from one of the interviewees, Sallie Ann Robinson, from her 2007 book Cooking the Gullah Way. As information that connects these images to a culture in the present, they are wonderful, but Weems’s series already contains text, so adding new panels feels like overload.

It’s the classic problem of art exhibitions—whether or not to explain what the art is about. The museum wins by making the series more accessible to less informed viewers, but some of the magic is lost in the process. More successful is the vestibule installation, a space separate from the gallery that includes a map showing the barrier islands, contextual information panels, a reading area, and headphones to listen to Smithsonian Folkways recordings of ring shouts and spirituals. This area prompts tourists to spot their resort on the map and reorient from vacation time to that land’s history—a lesson that benefits everyone, from those seeking to protect Gullah culture to the economic development that threatens it.

The gallery space is expertly laid out, using a temporary wall to guide visitors to the left, looking at the images in a clockwise pattern through the room and concluding at a triptych that feels like a punch in the gut. Instead of recreated tableaus or haunting spaces absent of figures, we come across the face of a very real woman from the 19th century, photographed in the nude like a biological specimen. These are not Weems’s own images, but appropriated images of daguerreotypes originally taken by J. T. Zealy in 1850. Here we see the brutal reality of slave life, the opposite of the poetic affirmation of the Gullah Geechee culture captured in the rest of the series. It’s this contrast of photographic imagery that drives the series as a whole, and that this exhibition makes possible to see now that the work has been temporarily reunited.

“Carrie Mae Weems: Sea Islands Series, 1991-1992” is on view at the Telfair Museums, Savannah, through May 6.

Rebecca Lee Reynolds is a lecturer in the department of art & design at Valdosta State University, where she teaches art history.