BY CARL ROJAS

Love him or not, Theaster Gates is arguably the most relevant American artist working today. His blend of visual art created from reused materials (think repurposed 1960s-era Alabama fire hoses), ceramics and social practice have made him one of the most powerful and respected artists in America.

On February 3, Gates gave a talk at Emory University in Atlanta titled “black space,” the term an intellectualization of what he has historically referred to as “the ‘hood,” especially as it relates to his block in South Chicago. Social practice is a substantive part of Gates’s art, and when he speaks about it he is soulful and entertaining, so it’s no surprise that he studied to a preacher (he earned an M.A. from the University of Cape Town in Fine Arts and Religious Studies). Gates is paid handsome sums for these appearances which, along with his healthy gallery sales, create what he calls the “circular ecological system” that funds the urban redevelopment projects for which he is best known.

In 2006, Gates was just another recent hire at the University of Chicago, having finished graduate studies at Iowa State, where he earned degrees in urban planning and ceramics. He was trying to make the most of his new home, in a former candy store on Dorchester Avenue on Chicago’s South Side. Gates was keen on moving his art practice out of the gallery space. In 2007, he began to host dinners at his home in “honor” of his ceramics mentor Shoji Yamaguchi, a fictive Japanese ceramicist who moved to Mississippi, married a black civil rights activist, and began a series of gatherings for which people discussed issues of race and politics. Through the lens of this fiction — African-American meets Asian fusion pottery — Gates enticed collectors to pay hundreds of dollars for his pottery, where before he had been lucky to garner $25.

Gates became intrigued by this “hustle,” a quality that threads through many of his projects, including the recently opened Stony Island Arts Bank. When he got a chance to meet with Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, he prepared for it, he said, as if it would be his one and only opportunity to meet with the mayor, so that instead of asking the mayor to do a small thing, he would persuade him to reimagine his own conception of art. And that is how Gates secured the Stony Island State Savings Bank building for $1 and transformed it into a cultural destination in South Chicago.

Gates acquired the large neo-Classical bank building with the stipulation that he fund the restoration without any further investment from the City of Chicago. In what must be one of the greatest art hustles ever, Gates took marble panels from the building’s interior walls, emblazoned “In Art We Trust” on them, called them “Bonds,” signed them, and sold them at Art Basel in 2013 for as much as $50,000 each. He sold all 100 and says he should have made more. In the current art market, the Gates bonds are increasing in value over time, just like the real thing.

Gates routinely emphasizes the happenstance nature of his work and career, and that his success is a byproduct of consequences he had little control over. He seized on every opportunity as if it were his last. In 2009, Gates decided to directly intervene in his neighborhood and invested his art earnings into his surroundings in an attempt to stop, or at least mitigate, the downward spiral in value he was witnessing. He bought the house next door to the former candy shop in which he was living, and also 14,000 books from a nearby bookstore that was going out of business to create a library for the neighborhood. When a record store also called it a day, he bought the entire inventory, which is displayed in the former candy store, changing its name to “Listening House.” Two years later, Gates bought a building across the street to create a screening room for black cinema. Together, these buildings — former neighborhood eyesores repurposed into inspirational black arts institutions — became known as the “Dorchester Projects.”

I first met Gates in Savannah in February 2014, when he spoke at the Savannah College of Art and Design as part of its deFINE Art Festival. His lecture was titled “An Analog but Very Important Conversation.” That night he opened his lecture by singing, a cappella, Lizz Wright’s “Walk with me, Lord,” which concluded with Gates making some facetious pleas to God: “Be my dealer Lord….Lord, why don’t you open a gallery?….this whole art market would be so much better…..” It is magical. (Watch it here.).

Gates would go on that night, as he does frequently, to speak about race and its relationship to place, who lives where and why (and that it’s okay not to get caught up in chasing the American white suburban dream), exhorting the audience to “woman up” and lead by doing for artists to lead by doing. Art as activism. Activism as art. Social practice. It was like a sermon; it was a sermon. Gates likes to preach.

The same apostolic plea was made from his Atlanta pulpit. In that February 2016 sermon, Gates expounded on the need for creating value in places where there is none, on building “altars,” places of meaning and value that are symbolically significant and serve as vehicles of cultural uplift. These altars strive to garner cultural capital that is equal to or better than their white space counterparts. Gates asserts that the Stony Island Arts Bank is such an altar, where the cultural events in “black space” not only celebrate but reproduce, affirm, promote and even enhance the goodness of its culture.

If this all sounds confusing, here’s an example. In 2010, Gates gets invited to Omaha by the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts, to perhaps do a project, which he begins with a “listening process,” a series of dialogues and dinners with artists, stakeholders and potential partners. He finds out there are 30 black artists in the area who have been applying for the institution’s residency program and have never been accepted. Gates tells them, “The institution will never accept you because you didn’t go to grad school. Your aesthetic is very different from what they’re interested in, and there might be a little bit of a cultural mash-up that they’re not sure they know what to do with. Why don’t we build a space over here that’s about the things you believe in, that can cater to you?” Eventually, they are able to acquire a small building — the Carver Bank building, the first black-owned bank in Omaha — from the city. In Gates’s words, they “trick it out” and it becomes a black space for black artists in that area. This is how “altars” are created. In Gates’s paradigm of social practice, “altars” are vehicles of cultural metamorphosis, disrupting the fabric of failure and prevalent racialist norms.

Among the questions Gates is regularly asked, including at Emory: “How do I/we take what you’re doing and make it work in my/our “hood,” in my/our black/brown/non-white space?” His response is well rehearsed: “I can’t tell you how to do it. You have to figure it for yourself.” At first it’s insulting, even arrogant. But over time it begins to resonate; there is no blueprint for an easy solution. Each “space” is different, with different starting points, different resources, different possibilities. He argues, fairly I think, that there has to be an emotional and resource-driven active investment from those in the “space” to find that answer.

I asked Gates if he were to do the Stony Island Arts Bank project all over again would he do it the same way. Without hesitation, he replied, “No. I learned better ways to do it.” He explained that part of the evolution of being an urban planner, a developer, was to learn about how to structure the financing for these investment projects, different ways to make them happen.

Gates also catches flak for his connections and relationships to individuals in business and government.

When asked about that at Emory, he said, “I know that they’re not all perfect. Mayor Rahm isn’t perfect, but it’s not about that. It’s about effectiveness, and that’s why the power relationships work.” Critics believe he should keep more ethical company.

Nonetheless, Gates’s notions are provocative and generate much-needed and substantive discourse about race, space, and being what Gates terms together. Here in Atlanta, as the Atlanta Falcons build a new altar for its football franchise, across the street from it on Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, the most significant civil rights neighborhood of the 1960s has one of the finest collections of boarded-up homes and dilapidated structures in the country. On those blocks, at Hunter Avenue Baptist Church, at Pascal’s, at the historically black universities nearby, a non-violent movement did indeed create a better version of America’s future. So, it would seem that if Theaster Gates can create substantive creative cultural institutions out of old banks, we could do the same with some of those boarded-up old buildings? Oh wait, it’s Atlanta, we’ll just tear them down and move on.

Carl Rojas writes about art when the spirit moves him. This is his first piece since he wrote about the demise of Friendship Baptist Church in Creative Loafing in 2014. He wants to make the old Paschal’s Restaurant an altar. He is also married to the editor of BURNAWAY.

Two Takes on Theaster Gates

Related Stories

Features

Reviews

Reviews

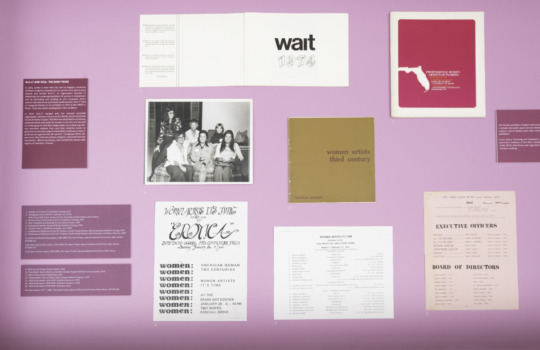

Women’s Voices: A Journey Through Miami’s Art History at Miami-Dade Public Library Central Branch, Miami

Carolina Ana Drake highlights the local legacies of Miami women artists in Women's Voices: A Journey Through Miami's Art History at Miami-Dade Public Library Central Branch, Miami.

A Landscaped Longed For: The Garden as Disturbance at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum, St. Augustine

Christopher Stephen reviews the visual metaphors of the garden found in A Landscape Longed For: The Garden as Disturbance at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum, St. Augustine.

As for me, I’m just passing through this planet at Bad Water, Knoxville

Harrison Wayne reviews the entangled sculptures and taxidermic specimens found in As for me, I’m just passing through this planet at Bad Water, Knoxville.