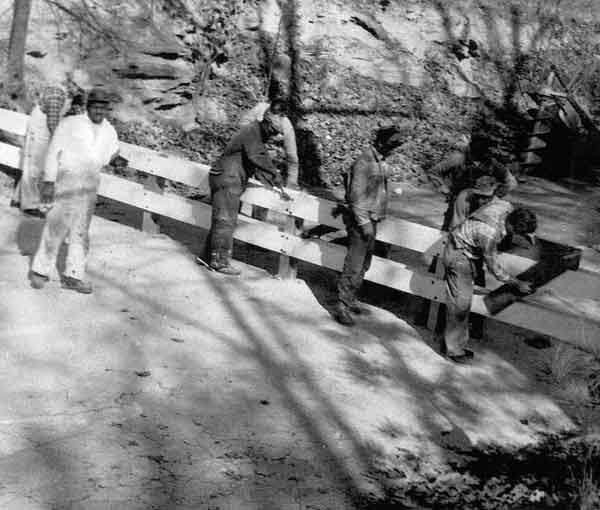

Fifty years ago, Mayor Ivan Allen almost spoiled Atlanta’s self-described reputation as the city ‘Too Busy Too Hate” with his attempt to block black home seekers from access to the all-white neighborhood of Cascade Heights, by erecting a barrier across Peyton Road and Harlan Road, which would in turn, halt access to the area from the black side of Gordon Road, (now Martin Luther King Drive). It was 1963, following the demise of Jim Crow laws, the era of white flight to the suburbs and black neighborhood expansion. Dubbed Atlanta’s “Berlin wall,” the barricades were taken down just a year later. Since then, Cascade Heights has become one of the city’s most affluent African-American neighborhoods—home to many figures, including former mayors Andrew Young, Shirley Franklin, and baseball home-run hero Hank Aaron.

Despite its reputation and prosperity, Cascade Heights has been facing a decline in economic stability. For one, the 2008 recession led to a dwindling number of homeowners, eateries, and retail shops, and an increase in vacant properties and neglected streetscapes. Hoping to bring about change, this past spring, a group of graduate students at the Georgia Tech School of Architecture, led by architecture professor Jihan Sherman, alongside the Cascade Heights Community Development Corporation (CDC), developed a comprehensive case study that reimagines the commercial district of Cascade Heights and the surrounding areas.

“Last spring, I taught a course exploring the relationships between urban form and community, with a particular focus on issues of collective identity, place making and community development,” Sherman said. “The Cascade Heights residents and I had been talking for over a year … [and] the district was a strong fit since it was a local condition [that was] trending in directions inconsistent with community desires.” According to Sherman, all these conditions led to questions about community identity, engagement, commercial development, and transportation.

It seems Cascade Heights remains a fading glory of its former self, with its declining property values, desolate corners, litter-ridden curbs, and uninviting walkspaces. But its residents have yet to give up on its historical hometown. In 2012, neighbors protested the building of a Family Dollar store at the corner of Benjamin E. Mays Drive and Fairburn Drive. They felt such discount retail chains are often poorly maintained, and only increase the number of low quality businesses, many of which often attract loiters and crime.

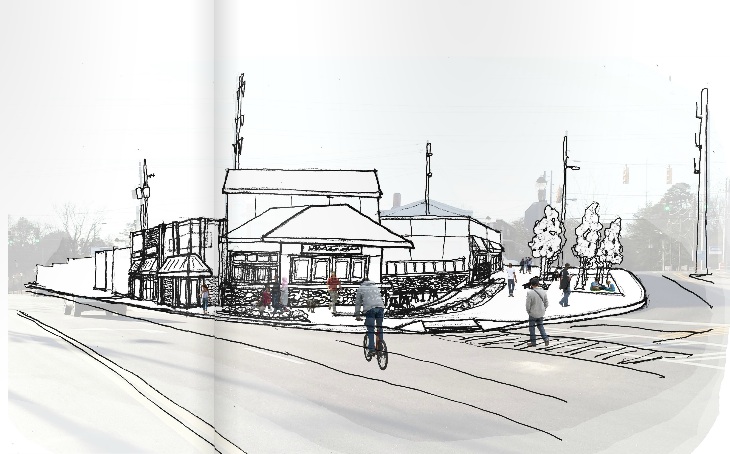

But there was a blinker of hope. In 2005, the city of Atlanta proposed its own Redevelopment Plan of Cascade Heights, in which members of the community, including stakeholders, business leaders, and key experts developed strategies to create a more vibrant and livable neighborhood. The plan listed the problems and prospective solutions on creating a better district, which included tackling area drugs and prostitution, implementing increase assistance for the elderly, and more pedestrian friendly streetscapes. This streetscape, particularly for the commercial district, would include adequate retail and green space, more streetlights, expansion of the existing sidewalks, and better public transportation. Some of the plan’s proposals were implemented, such as updated sidewalks and new lighting along Cascade Road and Campbellton Road. But economic hurdles left the project incomplete.

Today, Sherman believes the Cascade Heights group initiative will be a key player in helping to bring about the necessary changes to revitalize the district. “In the past, since the district is at the intersection of several different neighborhoods, [citizen advisors] and City Council districts, [creating] a unifying community voice… has been challenging. [But] the Cascade Heights CDC can be a great vehicle for connecting the vibrant communities to the commercial core itself.”

Sherman and the CDC found that the district was in need of a major facelift. While there were already community efforts being made to revitalize the southwest Atlanta area, the Georgia Tech urban design workshop allowed students to gain hands on experience through a major case study.

Highlighting the relationship between individuals and places, the Georgia Tech study uses community involvement as a necessary strategy to redevelop the district. The CDC is made up of longtime neighborhood residents and experts in urban planning and design, including prominent architect Oscar Harris, whose design work includes Hartsfield-Jackson Airport and Centennial Olympic Park. Its approach is holistic, opting for a ground-up approach, where the community is encouraged to participate each step of the way.

“If you want to make a neighborhood better, everyone in the community must be involved,” says Richard Dagenhart, interim chair of the Georgia Tech School of Architecture. “It takes time and energy, and it’s sometimes painful to experience, but everyone plays a vital role. Top-down approaches don’t work. A grassroots effort is always more effective.”

Despite its invisibility, Cascade Heights remains one of the city’s most affluent communities for Atlanta’s black elite, from politicians to attorneys, to civil rights leaders, athletes, educators and artists, many whose names can be found on street signs, highways, and buildings throughout the Capital of the South. And as Atlanta continues to transform from a detached urban sprawl, and merge into a vibrant, community-friendly metropolitan centre, the efforts of the CDC are now more important than ever. “We want our area to be one of the places to go when you visit Atlanta,” Danita Brown of the CDC says, “Just like Midtown or Auburn Avenue, this area is rich in history and culture and needs to be recognized.”

Annabella Jean-Laurent is an Atlanta-based freelance writer who blogs at militantbarbie.com. Her writing explores race, media, and gender in society.

This project is supported by the Georgia Humanities Council and the National Endowment for the Humanities and through appropriations from the Georgia General Assembly.