Everyday seeing has its limits. Stare hard toward the horizon and your eyes slip as they grasp at elusive details that hover just beyond their resolving power. Seeing the night sky offers similar challenges and discomforts. The visible lights are distant and dim, and offer few clues to their true nature. The blackness between them may look like the purest void, but this too is only an artifact of our weak, unaided sight.

Thanks to the sciences of astrophysics and cosmology, we can transcend these limits and build theoretical models that deliver detailed quantitative descriptions of the dimensions, age, and composition of the universe. Telescopes and other astronomical instruments come to our aid, stretching our vision across light years to bring us into seemingly direct contact with this ancient, distant realm. Even our best mechanically augmented seeing gives out eventually, though. At the ultimate limit of sight, currently around 13.3 billion light years, lie the oldest detectable galaxies and protogalaxies. Beyond them, our view dissolves into things that are no longer recognizable as objects at all, a world that can be theorized but never experienced.

102 by 74 inches.

The influx of astronomical technologies and images has given artists rich new materials to work with. Artistic practices that draw on the sciences, however, face daunting interpretive challenges. Scientific images have determinate meanings that are established by the experimental and theoretical context in which they are produced. How much of the autonomous meaning of these images appears when they are incorporated in artworks? To what extent do these artworks depend for their coherence and success on the surrounding scientific context? And how do these works clarify or complicate the scientific attempt to transcend our perceptually grounded understanding of the world?

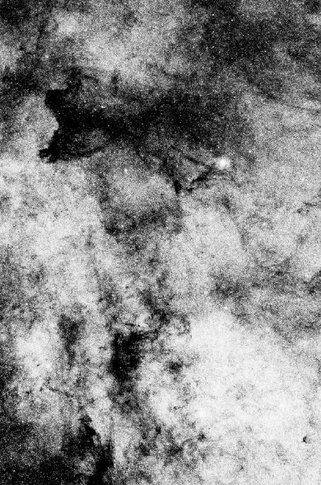

Art that entangles itself with science can follow several possible trajectories. Many such works involve the relatively straightforward appropriation of scientific images. Thomas Ruff’s Stars series (1989–92), for example, consists of copied, cropped, and enlarged pictures of star fields taken at the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in Chile. These images were originally part of a celestial survey, a catalogue of objects visible from the Southern Hemisphere. Apart from his curatorial role, Ruff’s primary aesthetic gesture was to blow up the images to massive size, although doing so only highlights the fact that pictures are hopelessly inadequate to convey the proper scale of astronomical subjects.

More importantly, the scientific meaning of these images vanishes once they are removed from their place in the catalogue relative to the other survey images and their accompanying lists of indexed objects. Ruff is interested in them for their “objectivity,” which for him seems synonymous with their having been mechanically produced. Because all photographs are mechanically produced, a more exact way of expressing this idea is to note that the images were produced by a mechanical process that could not possibly have been carried out by a human artist, or indeed by any human being at all. The technology of generating these astronomical images has virtually nothing to do with hand-camerawork.

To appreciate this point, consider that the deepest image of the sky, taken by the Hubble eXtreme Deep Field (XDF), required a combined exposure time of 2 million seconds, or more than 23 days of “looking.” No human hand or eye could position the apparatus correctly, hold it steady enough, or track the tiny target region (measuring 2.3 by 2.0 arcminutes) to continuously correct for the motion of the earth. The modern ESO array is actually four different telescopes that use optical interferometry to act as a single reflector, and the XDF project produces its final images by digitally combining more than 2,000 separate images derived from multiple instruments operating on visible and near-infrared light.

These processes are as distant as one could possibly get from everyday acts of seeing and from the skills used in most ordinary photography. Ruff’s reduction of his own artistic role to virtually nothing can be seen as a self-erasure that mirrors the collective, mechanical, and authorless process of modern scientific image-making. Other artists using scientific images have followed a similar path, such as Guillermo Gudiño in his Infinite Longing (2013), which incorporates landscapes shot by the Mars rover Curiosity. These works represent the point at which scientific image-making becomes a maximally alien enterprise.

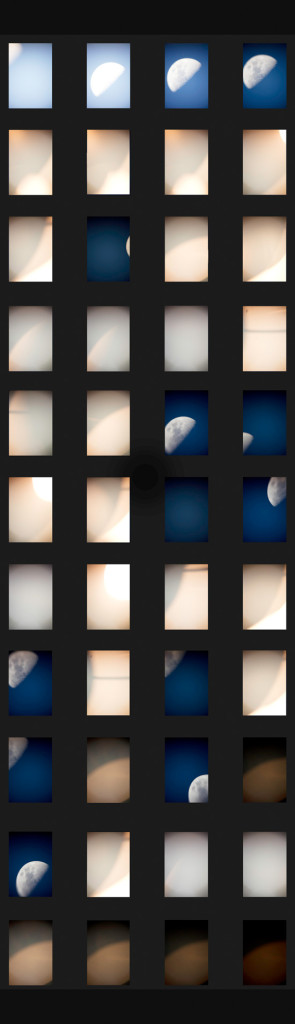

It is possible to move in the opposite direction, however, and use these technologies of prosthetic vision in a way that draws attention back to the act of seeing, to the hand and eye of the observer herself. This approach is best exemplified by Sharon Harper’s photographs of the sky, stars, and moon. In Sun/Moon (Trying to See through a Telescope) (2010–), the pictures she produces are, by astronomical standards, “bad” ones. They contain distortions and reflections from the telescope itself, as well as objects that are off-center, blurry, or so rapidly exposed that they appear fragmented into distorted copies. Anyone who has learned to use a handheld telescope will be familiar with this kind of awkward seeing, when nothing will sit still or stay focused. Rather than the neat, orderly arcs traced in technically proficient long-exposure shots of stellar motion, the multiple exposures in Moon Studies and Star Scratches (2003–09) collapse time haphazardly. Dozens of moons are scattered among fractured, interrupted star lines that resemble meteor trails.

Ruff and Harper highlight two different points in the history of scientific investigation. Harper focuses on the initial, exploratory stages, when one struggles with the newness and unfamiliarity of the apparatus. Learning to see the phenomena requires both retraining the hand and reconceiving the world. Her pictures are visual records of the novice’s epistemic disorientation. Ruff’s images represent the end products of Big Science: established, collective, expensive, using technological apparatus that is literally “out-of-hand.” Here, the world already exists in sharp focus, labeled and collected.

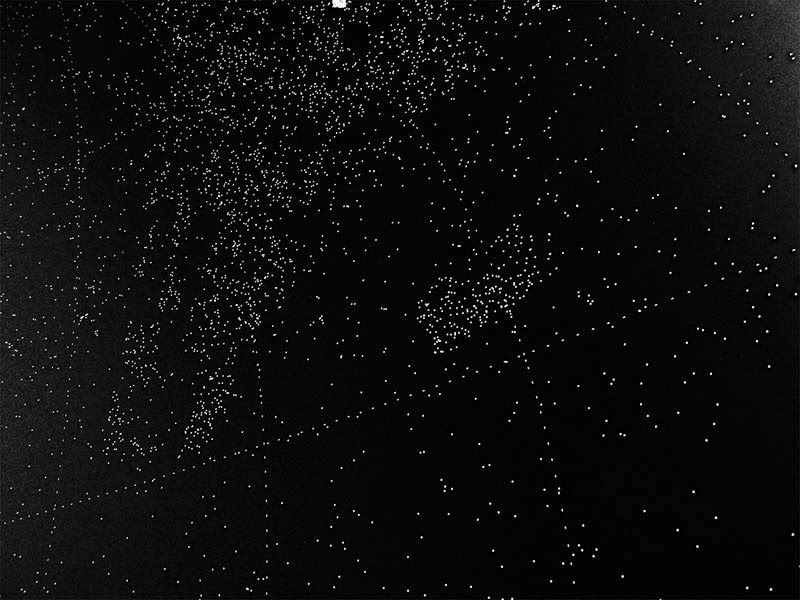

Other works explicitly address the limits of even the most powerful scientific representations. In History of Darkness (2010–), Katie Paterson assembles a box containing 2,200 slides, each one a “picture of darkness” from various times and places in the universe. The slides are uniformly black, each one labeled with a distance in light years indicating how far away from Earth this particular patch of darkness is. The slides are distinguished only by their handwritten numbers, since there is no purely visual way to represent a distance to an identical blank space.

It is tempting to read these works as familiar photographic gestures towards abstraction, but this interpretation ignores the most interesting questions about the origins of the images themselves. There are many methods in astronomy for measuring the distance to moving objects or energy sources: parallax motion, photometry and spectroscopy, measurement of red shift. However, there is no way to take a picture of a region of space that contains no detectable matter or energy and calculate how distant it is. Paterson began with a picture containing an object whose distance could be measured, then located a small black region off to one side and cropped it out. The distance to the object was then assigned to its adjacent blackness. The images are therefore ultra-minimal versions of Ruff’s star fields.

What are these slivers of darkness showing us? Billions of light years away—which is to say, billions of years ago—something emitted a cascade of photons in our direction. Here and now, for a few brief hours, we happened to point a telescope in the direction of some of those photons, open the aperture, and register their presence. Paterson’s images of blackness signify the fact that at least for a few hours several billion years ago, nothing in that region of space sent any unintercepted photons in our direction. But this depicted blackness should never be confused with emptiness. For all the images tell us, the world may be full of light that just happens to be moving in the wrong directions, or objects that emit their light outside of the imperceptibly brief moment when we glanced their way.

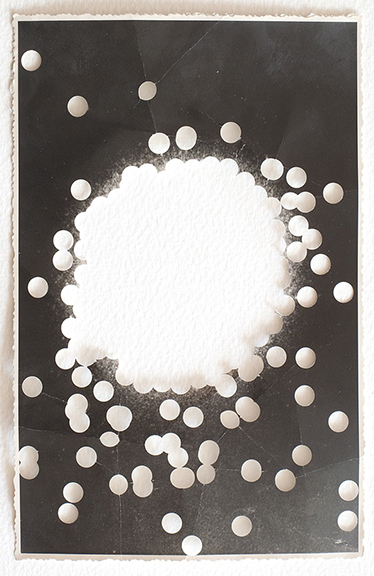

The harder you think about the technology of representation, the more aware you become of its many contingencies and failure points. Paterson’s works serve as a caution and a reminder not to substitute naïve faith in scientific representation as a remedy for the limits of everyday seeing. Similar cautionary themes are at work in Aspen Mays’s Punched Out Stars (2011), a series made while she was on a Fulbright Fellowship at the University of Chile’s Astronomical Observatory. Mays took old, discarded silver gelatin prints of star fields she found in the Observatory’s basement and used a hole punch to remove every visible star. The results look like the photographs have been shot up with a Tommy gun: the already aged and creased prints are crisscrossed with holes, and gappy where formerly dense regions of stars have been punched out entirely.

The blackness of Mays’s mutilated stellar images functions differently than in Paterson’s meticulously excised slides. Creating holes or literal absences within a picture is a way of drawing attention to the indirect and highly mediated nature of astronomical images. Our experience with earthbound photography may still tempt us to cling to the notion that astronomical images are a simple window on their subjects. But whether a star, galaxy, or cluster is really there is never something that can be simply read off of a picture. Stellar photographs are visual evidence or data, but as data, they give us information only when processed and interpreted through the appropriate theories. To use them correctly, we need to go beyond mere looking. Mays’s work emphasizes the fragility of scientific images, linking their delicate material existence to their uncertainty as evidence.

The works considered here trace out two paths, one of deference and another of critique. On the deferential side, we always have the option of simply gazing rapturously at Ruff’s enormous star fields or Paterson’s cryptic darknesses, absorbing their strange beauty or hoping to experience some final shudder of the exhausted sublime. But to properly understand what we are seeing, we need to understand the theoretical and technological context of their production. These works can be conceptualized as pointers, directing our attention toward facts that receive their sharpest articulation within the discourse of science itself. It is ultimately these facts that give the works their meaning. On the critical side, Harper’s phenomenological investigations are reminders that even the most sophisticated and seemingly transcendent inquiries ultimately have their origins in shaky human hands. Mays’s damaged representations hint that even our best images of the world contain absences, blind spots that become visible only at some distance from the images themselves. These works critique scientific practice by using its own materials and products.

41 by 97½ inches.

Beyond these paths lie many others. There are technology-dependent artworks that can be regarded as genuinely new scientific objects in their own right; examples include Paterson’s maps of dead stars, or Anna Von Mertens’s digitally derived quilts incorporating hand-stitched representations of stellar motion (As the Stars Go By, 2006–). Other works make use of scientific strategies for intervening in the world, such as Christian Bök’s attempt to encode poems in the DNA of bacteria (Xenotext, 2008–), or Trevor Paglen’s permanent photo exhibition located in geostationary orbit (The Last Pictures, 2012). These examples are merely initial, exploratory sketches of how artistic practices can transform and enrich the meanings of scientific images.

The author would like to thank Jess Jones for the reference to Anna Von Mertens, and Dan Scharf for his guidance through the astrophysics of darkness.

Dan Weiskopf is an associate professor of philosophy and an associate faculty member in the Neuroscience Institute at Georgia StateUniversity. He is the author, with Fred Adams, of An Introduction to the Philosophy of Psychology, forthcoming from Cambridge University Press.