These days, some collectors buy and sell art like a commodity, never laying hands on the work. It goes from the gallery or studio to a storage facility, where it might trade hands or eventually go to auction. Other collectors take pride in what they’ve accumulated, living among the works in a very intimate setting.

Neal Schott belongs to the latter group. His Cumming home, surrounded by forest, has “an Adirondack feel,” he says, which bears out in furniture and objects made from carved wood and antlers (Schott’s company, Gregory and Casey Textiles, represents fabric mills and sells wrought iron chandeliers and wood furniture). A deer trophy made of found sheet metal by Gordon Chandler riffs on the lodge theme. An amazing cuckoo clock from the 1880s, modernized so that it runs on a battery, resides over a rustic fireplace. “That was one of my best finds,” he says, “It’s huge when it’s on the ground, but up there the scale is perfect.”

Schott has been collecting since 1984: first a print by Andy Warhol, then four more. Soon he moved on to paintings because he wanted unique pieces. He started with works by local artists then expanded to New York-based artists. Many of the artworks he has collected were purchased through Fay Gold (Gordon Chandler, Andres Serrano, Louise Nevelson), in addition to Get This, (Jenene Nagy, Drew Conrad, Andy Moon Wilson), Sandler Hudson, and Marcia Wood. But he cites his artist friend Bill Stewart as his biggest influence.

Unlike collectors who use advisors like stockbrokers, Schott says he has always bought what he liked. “That’s the one thing I learned from the beginning. There are certain things you buy because you know it’s going to be worth money one day, and there’s some you buy just because you like it. You know it’s more decorative, and it may not have any value, but it has some value to you.” Quirky finds like sconces or ceramic mushrooms at Pier Shows are as meaningful to him as works by big-name artists from blue chip galleries. Those Lady and the Tramp figurines” on a nightstand? “It’s one of my favorite movies,” he says.

Noting the fickleness of the art market, Schott mentions his friend Lawrence Gipe. “I have a lot of his pieces. He’s a great painter, and in the ’90s there was a waiting list for his work. But things change. It’s sort of supply and demand. If the right people collect it, all of a sudden it has value.” Among his Gipe works is a large-scale painting that at first looks like a stodgy museum interior; in fact, it depicts the installation of a 1937 propaganda exhibition of Hitler-approved art, a work that garners more interest once the subtle irony is revealed.

In a bedroom, sitting in front of a Gipe painting from 1991, is a Louise Nevelson sculpture that resembles a New York skyscraper, purchased from Pace Gallery via Fay Gold. “I wish it was from the late ’50s,” says Schott, referring to the artist’s peak years, “but it’s from the ’80s.” Similarly indicative of the sporting nature of many collectors, he says of a 1980s William Wegman painting, “Obviously, he’s known for his photographs, but I have probably the only painting of his in Atlanta.”

One of the first things visitors see upon entering Schott’s home is a Sarah Morris painting in the second-floor loft, a characteristic canvas of traversing lines and planes of color that seems to interact with the house’s crisscrossing beams and architecture. “I’ve been looking at her work for years and years, and I was finally able to get this piece. There were four pieces available. MOMA and Donald Marron each bought one.” In 2006, the painting was replicated, on a massive scale, on the lobby ceiling of the Lever House (owned by mega collector Aby Rosen).

Just as meaningfully placed are an early Radcliffe Bailey hanging in the kitchen and another in a guest bedroom. “I’ve followed his work from the beginning,” Schott says of Bailey, “and I’ve seen him evolve from being very raw and rustic in the beginning to making these newer pieces that are a little more refined.” In the study, two of Scott Ingram’s nail polish paintings bracket a window overlooking the woods. Throughout his home, Schott has works by other Atlanta artists, such as Michael Gibson, Carolyn Carr, Andy Moon Wilson, and Todd Murphy.

A large canvas of undulating and swirling lines of color by Karin Davie fills a wall in the dining room, one of a few works by the New York artist that he owns. “I originally wanted a Sue Williams for this wall, but that never happened, for one reason or another,” he says. “And then I saw this and loved it.” An engaged collector, he can often explain how or why a work was made. “She starts at one point with each color and does a continuous stoke,” he says of Davie’s technique.

In the kitchen, shelves are filled with dozens of ceramic Pixies by Holt Howard from the 1950s, and hanging nearby is a wall construction by Drew Conrad, who’s known for large-scale architectural sculptures seemingly blackened by fire and dusty with time. Schott purchased the Conrad from Fitzroy Gallery in New York after noticing his work on a computer screen and learning that it was the subject of the gallery’s next show. Curiosity (and perhaps the thrill of the chase) led to him visiting with Conrad while he installed the show. “I really wanted to buy a larger piece, but space was at a premium and I knew this would work perfectly right here,” Schott says of the wall piece, which resembles a fragment of wooden wall laths.

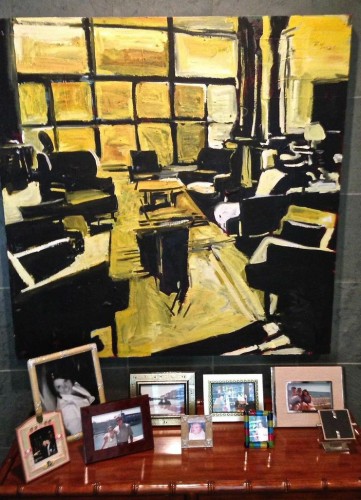

Schott’s evolving taste can be traced throughout his home. “For a while I was into work that was really precise and perfect,” like the Takashi Murakami paintings he has in storage, and a Michael Bevilacqua work purchased around the same time. But his favorite work is tucked into his spacious bathroom, where he can see it every day. It’s a brushy yellow and black painting of a boardroom interior by California-based German painter Roger Herman. “It’s the opposite direction from what I was collecting when I liked everything precise and cut with razor.”

Even less fastidious are two works by Leslie Wayne, who recently had a show at SCAD Atlanta’s Gallery 1600. Purchased from Jack Shainman Gallery in New York and hung over separate doorways, they are thick cubes made of paint, with deep gouges that reveal underlying layers of color.

In a lower-level living area, placed unobtrusively in a corner, is a multimedia work by Julian LaVerdiere, co-designer of the annual 9/11 Tribute in Light. It’s one of the few works in a nontraditional medium on view in Schott’s house. LaVerdiere, who works in the film industry, is known for some ambitious, large-scale works using optical effects. This modest pedestal piece features an antique Balm of Life medicine bottle suspended in a vitrine. The bottle is visible from a distance but increasingly obfuscated as one approaches, an effect achieved with a special lens and halogen light.

Though Schott collects works in all sizes—appreciating the intimate as much as the big statements—he isn’t too shy to ask for something bigger. From Thierry Goldberg in New York, he acquired a 36-by-36-inch work by Megan Whitmarsh, who usually works on a smaller scale, after seeing some of the artist’s more typically sized pieces during Art Basel Miami Beach.

And Schott scored an impressive carved wood sculpture—a horse morphing from a tree—from an artisan in Bali, whose workshop was filled with “all of these tiny little wood horses,” he recalls. After he asked whether they had something big, he was taken to the back where the artisan was midway through carving the 7-foot-tall piece. “Almost everything in this house, I remember where I was and how excited I was about finding it. That’s a big part of collecting.”

Collecting: Neal Schott—Home is Where the Art Is

Related Stories

Reviews

Reviews

Features

A Landscaped Longed For: The Garden as Disturbance at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum, St. Augustine

Christopher Stephen reviews the visual metaphors of the garden found in A Landscape Longed For: The Garden as Disturbance at the Crisp-Ellert Art Museum, St. Augustine.

Orchid Daze by Lillian Blades at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens

Blake Belcher reviews Atlanta-based Bahamian artist Lillian Blades' new work engaging orchids, transplantation, and diaspora at the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

Fictions More Precious by Rodell Warner at Big Medium, Austin

Natalie Willis Whylly explores memory, colonial archives, and encounter in Rodell Warner's Fictions More Precious at Big Medium, Austin.