[cont.]

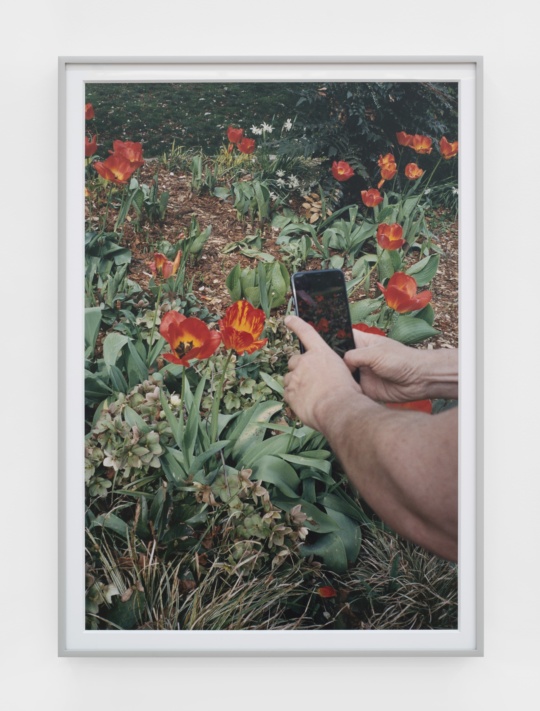

When Odessa straight out asked her to talk about the imagery, the only response Kay did offer was, “I prefer viewers to be free to have their own interpretation.” That answer is generally a clear sign that the artist is an amateur. How did she get through a graduate program without being able to articulate anything about her work? Even a discussion of technique would be a better pitch than this silence. Maybe Kay found her intimidating. So Odessa tried to seem more approachable by telling her that having Jack had changed her priorities and outlook. Did Kay find that having a son impacted her work? Kay ignored the question, continued glaring past Odessa into the tiny room, with a slight frown. The questions obviously annoyed her.

Finally, after standing awkwardly for a couple of minutes in complete silence, Odessa shrugged and backed out of the doorway, making a mental note to ask Paula why she had recommended this artist. No ideas, no originality, the most boring colors on the planet. Why on earth would Paula think she would respond to these paintings? Then she realized that Paula was also a single mom. Perhaps she felt sorry for her. Didn’t Paula teach a few classes at the school Kay had attended? Maybe Kay was more articulate under other circumstances? The most plausible explanation was that Kay wasn’t particularly interested in showing with Odessa and did the studio visit out of some misguided obligation to Paula.

As Odessa waded through the toys to reach the front door, feeling somewhat embarrassed that she’d been there only ten minutes, she mentioned in passing, as filler really, that she was flying to New York later in the month. Kay, with a face as blank as her art, told her, “I’ve never felt the need to go to New York.”

“New York is a great place to visit. The Met alone is worth the trip.”

“We have world class museums here.”

Given that attitude, maybe it was just as well that Kay had nothing to say about her own art work. Granted LA is a really great place to live with a good and vital art scene but anyone who thought LA was the end-all, be-all of art was provincial or myopic. No one place had everything. Did Kay know Odessa had lived in New York for years? Was she deliberately being insulting?

She couldn’t wait to get away. To top it off, she almost immediately got stuck in a SigAlert on the 5. Sunday mornings usually were good for traveling but not this morning. An hour later she had inched less than a quarter of a mile to reach the off-ramp and then proceeded to hit five red lights in a row. She could hear Dennis insisting that even old bowels moved faster than traffic in LA. He said that right after Maggie moved in and she went into hysterics over it. They really did have identical senses of humor. Maybe humor is partially genetic? A big blue SUV jolted her out of that reverie by abruptly shifting lanes without signaling, forcing Odessa to slam on the brakes. She honked the horn in annoyance, forgetting that was considered bad manners in LA. Really, she had to start doing studio visits in sectors, not hither and yon. And shouldn’t there be some sort of rule that visits had to last longer than the drive to get there?

Dick’s studio in Highland Park was in his garage. As she walked down the narrow driveway past the windows of his house, she could see a variety of paintings on the walls, some obviously not his. Inside the studio, announcements and sketches were taped onto the metal garage door. Paintings leaned against a wall. It was obvious he had cleaned the studio for her: piles of dirt and dog hair sat on top of the other contents of the trash bin. He also had a small tray of cheese and crackers and a bottle of French water waiting for her. The table top and chair had been wiped clean.

“I’m sorry the studio isn’t neater,” he told her. “I haven’t had time to build the racks yet. It feels like we’re still unpacking.”

She asked him how he liked living in southern California.

“The light here is nothing short of miraculous and it’s so much quieter and cleaner than New York. Unfortunately, my wife is already complaining about the commute, so I don’t know if we’ll be staying in this neighborhood. She’s so used to taking the subway. I got her some books on tape so we’ll see if that helps.”

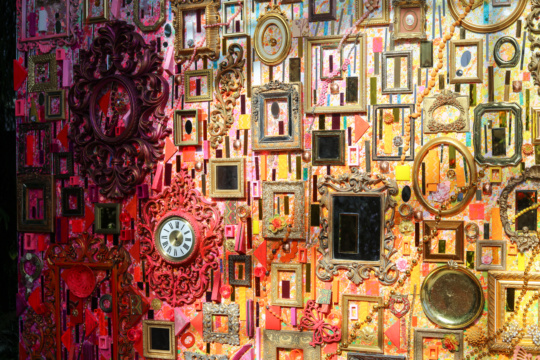

Dick was the exact opposite of Kay except in formal structure. He too did geometric abstraction but on top of a similar composition, he painted linear explosions in candy coated colors. “I use auto body enamels,” he explained. Odessa asked him about influences and Dick told her he had just returned from visiting Paris so they talked about the Louvre, the Marie de Medici paintings by Rubens in particular. Odessa admired Rubens’ brush strokes but couldn’t stomach the subject matter. Pomposity made manifest. Dick disagreed, asserting that Rubens was about zest in life. When Odessa asked if it had to be an either/or situation, couldn’t both positions hold true? Dick reluctantly agreed. Little fleshy cupids and lardy nude women were not her cup of tea and no amount of enthusiasm from other people could change that. Odessa preferred two of Rubens’ contemporaries, Caravaggio and Rembrandt, who were more analytical. Dick protested that Rembrandt was not analytical. And Odessa pointed out that what made Rembrandt’s emotional content so potent and evocative was his use of chiaroscuro, his rich use of light and dark. Both Caravaggio and Rembrandt were keenly and accurately observant of the impact of light, while Rubens was a master of depicting ceremony. Dick argued that Rembrandt and Caravaggio were as theatrical as Rubens and Odessa agreed, but the intent was different. Caravaggio featured “real,” non-noble, non-idealized figures in his religious paintings, integrating the divine with the commonplace thus including the viewers. Rembrandt‘s deep shadows made his paintings mysterious and intimate, drawing his viewers into his world. Rubens, though, used every trick in the trade, and some he invented, to show the trappings of power, keeping viewers in awe at a distance from the action on the canvas, keeping them mere spectators. That started them discussing the contemporary artists he enjoyed and why his work wasn’t like theirs. In short, Odessa had a great time discussing art with Dick.

When she got home, Dick had emailed her a thank you with a link to an article about his work. Kay did nothing. Odessa laughed: she couldn’t get a clearer commentary on the division between the New York and Los Angeles art scenes. New Yorkers viewed art as a serious profession and LA artists liked to look more lackadaisical. This had interesting consequences. As Maggie would say, our virtues are also our vices. Even grocers in Brooklyn viewed art as a real profession. Everyone in LA viewed art as a kind of therapy and that was reflected in the lower prices and minimal respect. New York artists obsessed with maintaining records of inventories and sales, insisted on consignment agreements, stored work archivally. She knew quite a few LA artists who stored unsold work outside behind sheds and she had the devil of a time forcing artists to pick up their work after a show. That lack of caring allowed LA artists to be more inventive and reckless. But carried too far, it just felt like amateur hour. If artists don’t value their own work, why should anyone else?

She liked Dick and his ideas and looked forward to talking with him again. She, however, wasn’t super thrilled with the work itself. Maybe his paintings would grow on her if she had them around for a month. An hour of viewing often wasn’t enough to make a firm decision. Maybe with a little guidance, his paintings would evolve into something as interesting as his observations. Dick was invited to be in the summer group show.

Kay’s info went into the trash.

Return on Friday for the next chapters of Just Like Suicide.