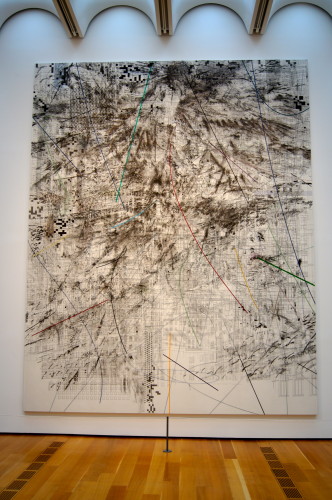

On Monday, April 21 at 7pm, Ethiopian-born New York artist Julie Mehretu will speak at the Alliance Theater (click here for ticket information). Maggie Davis recently spoke to the artist about the complex meanings of her densely rendered, architecturally inspired paintings, in particular a 15-foot-tall work acquired last year by the High Museum of Art, which is the event organizer. [divider top=”no”]

Julie Mehretu’s radical approach to painting speaks directly to the time in which we live. History unfolds globally as recent protests in Venezuela, Ukraine, and Thailand are broadcast live from public squares. Social media, 24-hour news channels, and embedded reporters feed us an avalanche of information with breaking news reports of every crisis from a missing jumbo jet to a Congress that is immobilized by its own dogma.

Mehretu’s large-scale painting Mogamma (A Painting in Four Parts) (Part II), recently acquired by the High Museum of Art, provides us a front row seat to ponder how painting can speak to global crisis. Mehretu interrogates painting’s place in this chaotic world of unrelenting information, of too many crises to care. If we take the time to consider her work, we will experience frustration, confusion, feelings of fear and eventually hopefulness.

The Mogamma cycle of four paintings was conceived as one painting in four parts. First in line among the buyers was High Museum director Michael Shapiro and modern and contemporary curator Michael Rooks. Rooks chose Mogamma (Part II), the panel that appears to anchor its three siblings as the source of energy for the entire group. The other panels were claimed by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; Tate Modern in London; and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

I caught up with Mehretu this week to discuss the concept behind the painting. Transparent and down-to-earth, she speaks with the same staccato pattern found in her mark-making, pushing words out in phrases. She talked about the four paintings as “separate but related, not to come together as a landscape or mural experience, but rather to break the wall up, into almost a meter, where they are different parts of a larger piece. These are the first vertical paintings.”

The Mogamma cycle introduces a multiplicity of ideas, as threads in a labyrinthine tapestry. Ideas about migration, resistance, revolution, time, history, and space comingle with her thoughts about music, altarpieces, and ritual. And not the least of Mehretu’s concerns is the events of the Arab Spring: self-immolation and self-determination, oppression and liberation, abstraction and representation.

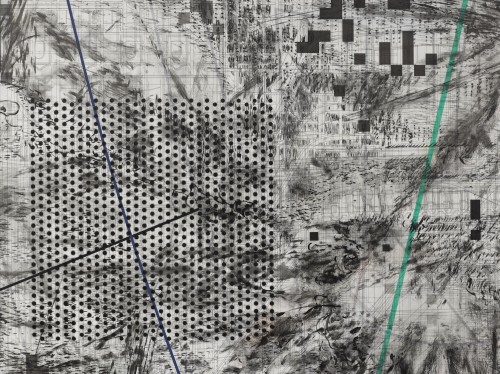

The title Mogamma refers to the government building that was exemplary of Cairo’s bureaucratic inefficiency and a flash point for the uprising in Tahrir Square in 2011. Employing over 18,000 civil servants, the Mogamma is typically crawling with lines of people waiting for applications, passports, visas, and driver licenses. Although it’s hard to identify visually, the structure appears in the painting cycle numerous times as upright or inverted, along with other sites of uprisings, including Zuccotti Park in Lower Manhattan, where Occupy Wall Street camped out for two months in 2011.

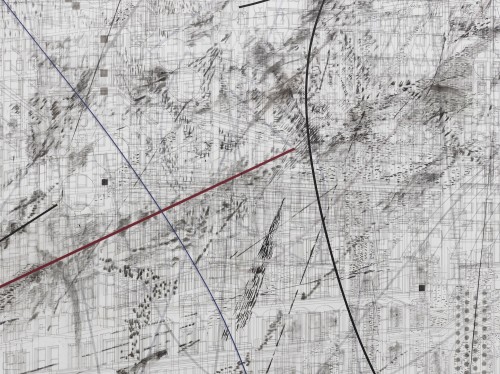

The painting is a testimony to the spirit of revolution that occurred in the Arab Spring. It collapses the uprisings in Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Yemen, and Syria into an explosion of marks and erasures that obliterate the bureaucratic symbols of power in the respective countries. Even the Ethiopean revolution, which caused Mehretu’s family to flee to the United States in 1977, is represented by lampposts surrounding the square in Addis Ababa, the artist’s birthplace.

In Mogamma (Part II), Mehretu covers the surface with layers of wire-frame architectural drawings overrun and enmeshed with frenetic marks and vectored lines that nearly obscure the underlying drawings. The upper half of the painting is more densely worked with marks exploding out from a small space close to the top that has been erased. Everything emanates from this center, falling away toward the phantom panels to the left and right. It is tempting to walk past this jumble of drawing, judging it as unreadable and without meaning. But the massive scale and density of the painting begs us to linger awhile to let the painting slowly unfold before our eyes.

The 15-foot-high Mogamma paintings bear reference to an altar format. “The paintings offer a ceremonial space, a new forum for social interaction, a participatory event,” Mehretu explained. The overpowering scale of Mogamma (Part II) diminishes us as it presents full force the violent and bloody bid for freedom from autocratic rule. We are led to imagine in a profoundly original way the unfolding of history in time and space.

I asked Mehretu about the challenge of reading even a single panel like Mogamma (Part II) as a whole. She explained, “The paintings require a performative experience. Rather than being able to read the painting, I see it as an emergent experience. The forms coalesce. The parts come together.” She asks us to become participants in the ceremony, permits the work to unfold over time through our engagement.

A slow reading of Mogamma (Part II) allows us to enter the sublime. The sublime, whether in pain or pleasure, disconnects us from the familiar. It opens us to potential. Encountering the painting, we are “being with” the artist as she was “being with” the Arab Spring insurgents when she made the painting. The numerous architectural drawings, the nervous marks, smudges, and erasures that operate in relation to each other while remaining isolated create a discontinuous space that puts us on edge. This edginess of not being able to knit the elements of the monumental painting into a whole creates what Mehretu calls a “third space.”

In an unpublished paper written as a graduate student in 2009, I suggested that Mehretu’s spatial project emerges through a tension between the precise mathematical drawings of architecture and the freewheeling agency of organically hand-drawn marks. The clash between the geopolitical structures and social agency suggests the potential of “third space.” It is in the third space between two competing forces that we encounter the sublime. It is at the margins of colliding spatial systems that the contemporary sublime emerges. The tension at the edge of unknowing carries with it the possibility of something altogether new emerging.

As an Ethiopian American, Mehretu brings authentic compassion to the potency of hybridity and to the struggles for identity characterized by the uprising of the Arab Spring. Her paintings, Mogamma (Part II) in particular, conjure a world on the edge of becoming.

Maggie Davis is an artist and scholar living in Roswell, Georgia.