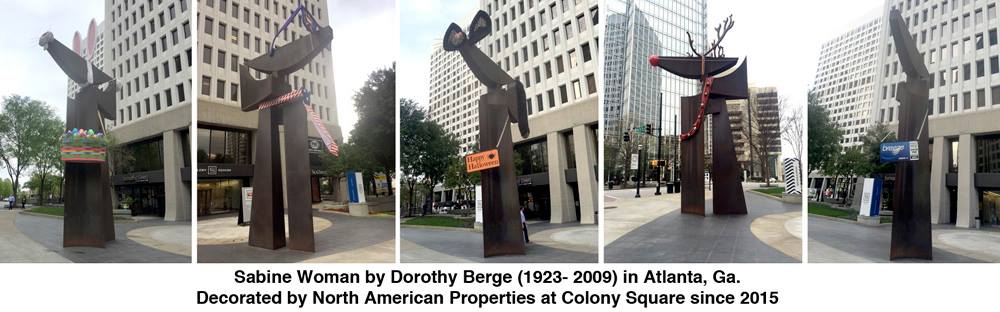

On the corner of 14th Street and Peachtree, there is a 30-foot giant, strong and defiant, her commanding gesture signifying a triumph over the passing cars and pedestrians below. But sometimes she wears cute bunny ears on her head.

This giant is actually a sculpture by Dorothy Berge titled Sabine Woman. Located in front of Colony Square, the sculpture, made of rugged Cor-Ten steel, is a subject of calendrical controversy. Since 2015, the work’s custodians have been in the habit of dressing up the sculpture in cute holiday accoutrements, raising the ire of members of Atlanta’s art community.

When I first saw photos of Sabine Woman, I have to admit, my mind veered to the comical side of sublime. The sculpture reminded me of an early ’80s illustration of a Transformers Megatron toy. Sabine Woman is an assertive sculpture, in its scale, in its materiality, and its suggestion of movement. I imagined her to be a bit of a brute, and envisioned pedestrians quickening their pace as they passed beneath.

But my perspective changed after seeing Sabine Woman in person. She isn’t dark and threatening at all. Strong, yes, but there is elegance to her, a real, graceful beauty in the simplicity of her form. She is a balance of soft curves and straight edges, subtlety and severity. The steel skin of Sabine Woman is pitted and a deep rust color and her patina is a delicate rainbow of greens, violets, and blues, like what one may see floating across the top of an oil slick.

The sculpture has not always occupied such a prominent location. In the 1990s, it was moved from its original spot out front and tucked away around the corner, “hidden” among bushes and trees. It was returned to its original location in 2014 by Tishman Speyer, then the property’s owner. But with the sale of the property to North American, its resurrection was met with conditions, the most offensive being its periodic demotion from artwork to holiday prop. In the spring, Sabine Woman is dressed as a giant leprechaun for Saint Patrick’s Day. Later she carries an Easter basket and wears a cute bunny nose, tall ears, and a cotton tail. Around the Fourth of July, she wears a patriotic necktie patterned with stars and stripes accompanied with matching sunglasses. At Christmastime, Sabine Woman is transformed into Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, with a bright red bulbous nose, antlers, and reins with giant jingle bells.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that many observers in the Atlanta art community do not find Sabine Woman’s holiday transformations endearing. Anne Lambert Tracht, an art consultant and member of the Metropolitan Public Art Coalition, is one vocal opponent. “Every time I see it decorated, I think it is incredibly embarrassing to the city and frankly to Colony Square,” she says. “They’re defacing someone’s artwork as a way to gain marketing attention for their property,” says Tracht, citing the number of selfies snapped in front of the decorated sculpture. “They do it to get a reaction, and it is not the reaction that is intended by the artist. If the artist were alive today she would probably have them in court.” Tracht acknowledges that there are historic sculptures that take on a life of their own in the public domain, but “to use this artwork as a marketing initiative is entirely different than having the community take hold of something from the distant past.”

But it is difficult to say with any certainty what Dorothy Berge’s position would be regarding the controversy. Berge died in 2009 and her estate has not expressed an opinion about the controversy [though a niece, Sue Selbitschka, weighed in on Peragine’s post]. We might make presumptions as to Berge’s intentions for her work by examining the historical context embedded within the title: Sabine Woman. The story of the Sabine women, a popular subject for Renaissance artists, is a tale from Roman mythology involving the new upstart Romans, who found themselves lacking wives in order to establish families. The neighboring Sabines distrusted the Romans and refused to intermarry with them. Consequently, the Romans performed a mass abduction and forced marriage of Sabine women. The fathers of the abducted women eventually retaliated against the Romans, leading to a bloody and protracted war. Having experienced the loss of both their husbands and fathers, the Sabine women put a stop the war by standing defiantly between the two armies, and declaring, according to the historian Livy, “It were better that we perish than live widowed or fatherless without one or other of you.”

This is heavy, dramatic stuff, arguably not the sort of thing one might want to put bunny ears on.

The owners of Colony Square and Sabine Woman have a different perspective. In a statement released by Liz Gillespie, Vice President of Marketing for North American Properties at Colony Square, when the company purchased the property, they found an underappreciated Sabine Woman. It had “faded into the streetscape, overshadowed by new developments in Midtown … no one seemed to notice her.” (However, Tishman Speyer was still the owner of Colony Square when the sculpture was moved, in June 2014; North American did not buy Colony Square until She says that, as part of their reimagining of Colony Square, they “saw the opportunity to breathe new life into Sabine Woman, to reenergize her, and revive interest in her story.” Gillespie says that the intent was to create “an artful encounter that joyfully engages guests and residents of Midtown, especially children.” She claims that many people believed that they had installed the sculpture because they hadn’t noticed it before its inaugural outing as Rudolph.

The argument that a large section of the public might not have stopped to appreciate Sabine Woman until they were lured in by the novelty of the holiday decorations is both positive and a bit troubling: positive in that it may lead a person to further appreciate Dorothy Berge’s work, or even more broadly, art in general. But it is also troubling that it might require decorative embellishment, a recontextualization, or an abandoning of the intentions of the artist in order to make this happen.

Michael Rooks, curator of modern and contemporary art at the High Museum of Art, offers a more nuanced but nonetheless vocal opposition to the Sabine Woman’s holiday transformations, telling me in an interview that, “I have an almost physical reaction when I see something that suggests disrespect, but I have to balance that with the fact that I don’t know what the artist’s intention was, and I don’t know what the owners’ intention is.” Nonetheless, Rooks hopes that a conversation may be started where all points of view are considered. “If this conversation devolved into a black and white issue, good and bad, I think that is a missed opportunity for us to help educate people who influence how this city takes shape.”

On the role of public sculpture, Rooks says, “There are two sides to the argument, historically. There is the argument that artists and their work are due our respect and the respect of the people who care for it in perpetuity. And then there is the argument that work in the public realm allows for a broad audience to encounter it in ways that are outside the context of an art museum, that are outside the conversations and intentions, even, of art and of the artist.”

Towards the end of our conversation, Rooks shared a more resigned perspective. “When something enters the public realm, I think you have to let go of certain things we cherish and hold very dear, because what we do, we do for a broader public, like it or not.”

In a way, this attitude of acceptance of the ephemeral nature of all things can be healthy, but it could also be an indictment of the failure of Visual Artists Rights Act of 1990, a sentiment echoed by many in the art world. VARA was enacted in the wake of the hotly disputed removal of Richard Serra’s sculpture Tilted Arc from in front of the Javits Federal Building in Lower Manhattan. Among VARA’s stipulations are that artists can prevent their work from “being displayed in an altered, distorted, or mutilated form.”

However, Berge’s Sabine Woman would not qualify for VARA protection because it was commissioned before December 1, 1990, when VARA was enacted, and because Berge died in 2009, and the artist’s rights expire upon the artist’s death.

While we do not know Berge’s specific intention for Sabine Woman, we do have a record of her thoughts regarding the body of work produced for her 1968 exhibition “Sculpture in Corrugated Board” at the High Museum, where she showed a cardboard model of the work that would be later become Sabine Woman. It was at this exhibition that real estate developer Jim Cushman first saw the model for Sabine Woman, which he would later commission for the plaza of his new project, Colony Square. In the catalogue for the exhibition, Berge wrote, “What comment I could now make on the sculptures themselves and my concept of their meaning, or reason for being, may be of little value to the viewer and perhaps redundant on my part.” If she only knew … She continued, “If I can communicate my idea of form and touch a raw nerve ending, so to speak, that will stimulate a greater awareness of the beauty of abstract form, I will be very happy.”

This may be the closest we can get to what Berge might think about the dressing-up controversy. Transforming Sabine Woman into something figurative, something with reindeer antlers, might not “stimulate a greater awareness of the beauty of abstract form.” But as hard as it may be to admit, we still can’t weigh in on how Berge might have felt about the decorations. She might have had a sense of humor about this whole affair, or been heartened by the viewer who is initially drawn in by the Rudolph nose, only to discover an appreciation for the abstract form beneath.

Correction: Artist Gregor Turk has been involved with public art in Atlanta for over two decades in a variety of capacities: artist, administrator, educator, grass-roots advocate, panelist, policy advisor, and tour guide. He told me that Berge was born in Illinois and called Minnesota home, but would later settle in Atlanta, where she earned her MFA from Georgia State University. He noted that the site where the Sabine Woman now stands was a gathering place for protestors of the war in Iraq — appropriate, perhaps, considering the Sabine women’s assertive plea for peace. He believes that “the decorations, despite being festive and amusing to some, simply trivialize the work.”