For Atlanta critic Cinque Hicks, art in 2013 posed a lot of abstract questions.

The Museum of Modern Art’s Inventing Abstraction and the Walker Art Center’s Painter Painter punctuated a year that led critic Pepe Karmel to assert that the golden age of abstract painting is right now. Be that as it may, 2013 for me was less a year of tabulating where abstraction begins and more a year of figuring out where it dissolves into something else. Here are seven Southern artists whose work lies somewhere on the spectrum between abstraction and representation.

Kevin Cole’s large-scale, abstract sculpture has always taken cues from family lore, cultural history, and the spiritual threads that link generations. But a few new works this year freshen the Atlanta artist’s vision with a focus on the recognizable image of Trayvon Martin as a figure echoing back to Emmett Till, ricocheting off Edvard Munch and Wes Craven along the way. Equal parts Frank Stella and Sam Gilliam, Cole has always used color as a form of structure. Now color becomes figure and narrative.

Willie Cole taps the fetishistic potency of antiquated objects. Shows in Birmingham [at beta pictoris gallery] and Greensboro [at the Weatherspoon Art Museum] gave us high-heeled shoes in the form of traditional African statuary or masks by turns African, Central Asian, or Pacific Northwestern. No form of mystical contemplation is off limits to Cole.

I’ve been trying to unlock Craig Drennen’s cryptic, pseudo-abstract paintings for years. Highly meticulous representational paintings of recognizable things—including paintings that quote various modes of painting—each of Drennen’s works bites off a fantastically huge chunk of art history. He inhabits a cyber-enabled world in which no visual image is the thing itself but is instead a rendering of that thing: Polaroid photos, pieces of rope, or cigarette butts. Abstraction is just another object in Drennen’s world of objects.

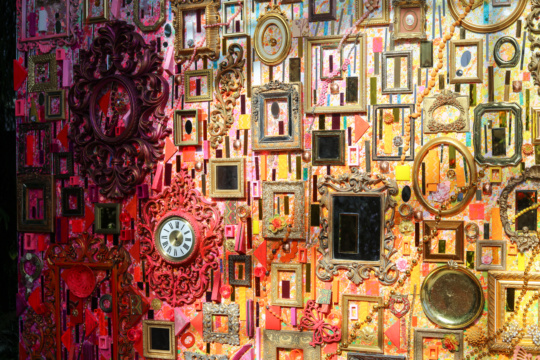

Speaking of the cyber world, Jiha Moon’s multimedia works similarly collapse the time and space of a networked world, where information creates its own physics. As seen in her exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, Moon’s works draw upon motifs as diverse as Japanese toys, corporate logos, and hippie fashion. They are manifestos of the hyperlinked world; a landscape of synchronized wormholes where “here” becomes “there” in the flattened noplace of an Instagram stream. Your real space, Moon seems to say, is already abstract.

Shara Hughes makes me glad I stopped painting. If I hadn’t, I would forever be comparing my own timid skills to Hughes’s ability to fearlessly remake the rules of pictorial composition or to her paint handling, which is about as macho as it comes. Hughes’s solo exhibition at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center featured a malevolent brew of disjointed bodies and tormented interiors ripped apart by the dictatorship of the brush, wet with paint, hot with confidence.

52 by 90 inches overall.

At Whitespace, Mimi Hart Silver’s paintings of animals slaughtered after the hunt are both terrifying and gorgeous. Blurriness, high-contrast, and eccentric compositions make the subject matter hard to see. But it also turns animal carcasses into angels.

Chase Westfall’s salacious, meaty paintings traffic in animal parts, too. But rather than raise the subject matter to the level of a spiritual encounter, the Tennessee artist’s paintings seems like an effort to push back the horrible mortality that lurks just beneath the skin of living things. In each work, cool, modernist geometries attempt and fail to hide the fleshy badassedness of skulls and blood. The best ones remind me that we all have an id. And all that nasty stuff it’s spewing out while you’re sitting there pretending to be civilized: it’s coming for you. And it ain’t pretty.

24 by 24 inches.