Based on the title of this essay, you’re probably thinking that the history of paint might be as exciting as, well, watching paint dry. But I’m going to attempt to convince you otherwise. Since the dawn of human history, we have sought to express ourselves through paint. The first example of paint-making was discovered a few years ago in South Africa, and it dates back about 100,000 years. The earliest paints would have used a variety of mineral and organic based pigments. The paint found in South Africa was made from red Iron Oxide and charcoal and used bone marrow as a binder. About 5,000 years ago as we left the Neolithic age and established the early stages of civilization in Greece and in Egypt, we started using beeswax, egg yolk, and milk as binders. We still use these binders, and others (such as gum arabic, linseed oil, and acrylic polymer), but our quest for color pigments has a much more varied and interesting history. Since those early days, we have used both cow’s urine and ground up Egyptian mummies as pigments. We have even made up elaborate stories involving elephants and dragons fighting to the death as a marketing ploy to sell paint. And perhaps even stranger, the first synthetic paint was invented by a necromancer, who, allegedly, influenced Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. And these are just some of the strange stories we’ll go through on our little trip through the history of paint.

Indian Yellow

According to one theory, Indian Yellow was made from the urine collected from cows that were force fed a diet of mango leaves. The urine was collected and dried, producing small foul-smelling balls of raw pigment called purree. Cows do not digest mango leaves very efficiently, as the leaves contain a toxin similar to poison ivy. Consequently, the cows were often thin and malnourished. Apparently, even though the cow has long been considered sacred by many in India, some did not think anything wrong with profiting from the cows’ slow starvation. The practice of producing Indian Yellow was declared inhumane and outlawed in 1908. The Indian Yellow we get in stores today is, thankfully, cruelty free, being synthesized from nickel.

Mummy Brown

As the name implies, Mummy Brown (also known as caput mortuum) was derived from the ground-up remains of Egyptian mummies mixed with pitch and myrrh. The pigment, a rich brown with a hint of purple, was great for producing transparent effects in glazing, shadows, and flesh tones, and was a favorite color in the palette of the Pre-Raphaelite painters. The pigment quickly lost its popularity once the secret of its composition became generally known to artists. The Pre-Raphaelite artist Edward Burne-Jones was reported to have ceremonially buried his tube of Mummy Brown in his garden once he discovered its true origins. By this time, however, the supply of available mummies had become exhausted.

Dragon’s Blood

From the time of the Romans up through Medieval times, Dragon’s Blood pigment was literally thought to have been derived from the congealed blood of dragons and elephants, mixed together as they fought in mortal combat. The truth to its production was a well-kept secret for over a thousand years, with the ancient world’s supply being exclusively produced on the small island of Socotra off the tip of the Arabian Peninsula. Dragon’s Blood pigment was produced from the sapped gum of a Dragon’s Blood tree, Dracaena cinnabari, and the story was most likely invented as a marketing device. Dragon’s Blood was used in the famous frescos in the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii. Unfortunately, the pigment is known to be extremely fugitive (it fades rapidly). In his handbook for painters, the 15th-century artist Cennino Cennini writes about Dragon’s Blood, “leave it alone and do not have much respect for it …” Dragon’s Blood has also been used by alchemists, in folk medicine, and in ritual magic by witchcraft and Hoodoo practitioners.

Prussian Blue

In 1704, Johann Conrad Dippel created the world’s first synthetic pigment, by accident. He was trying to produce a red pigment but instead invented Prussian Blue (also known as Berlin Blue), which is known for its deep, blue-black color. Dippel was a controversial figure, a mad scientist type who was rumored to have sold his soul to the devil in exchange for secret knowledge, and who most certainly dabbled in alchemy and illegal anatomy studies in his laboratory in Castle Frankenstein in Germany. Having found himself imprisoned for heresy for seven years and banned from Russia and Sweden, Dippel was secretive with his work, which, of course, only fueled the rumors. In the course of one of his experiments, Dippel is said to have accidentally blown up one of the castle’s towers, though this is likely a myth. It is also said that he tried to reanimate the dead, worked at transferring the soul of one cadaver to another via a funnel, and boiled and distilled human body parts while seeking to create the Alchemical Elixir of Life (an immortality potion). It should come as no surprise, then, that Dippel is believed by some scholars to have been the inspiration behind Mary Shelley’s character Dr. Victor Frankenstein in her novel Frankenstein. Dippel also invented Prussic acid, which like Prussian Blue, is derived from cyanide. There is yet another rumor concerning Dippel, that he slowly poisoned himself to death by taking Prussic acid as a supplement and that when his body was discovered it was a tint of Prussian Blue. Prussian Blue would go on to have an even more grisly history. The poisonous gas Zyklon B, used by the Nazis during the Holocaust, was also derived from cyanide. Consequently, the walls of the gas chambers are stained Prussian Blue.

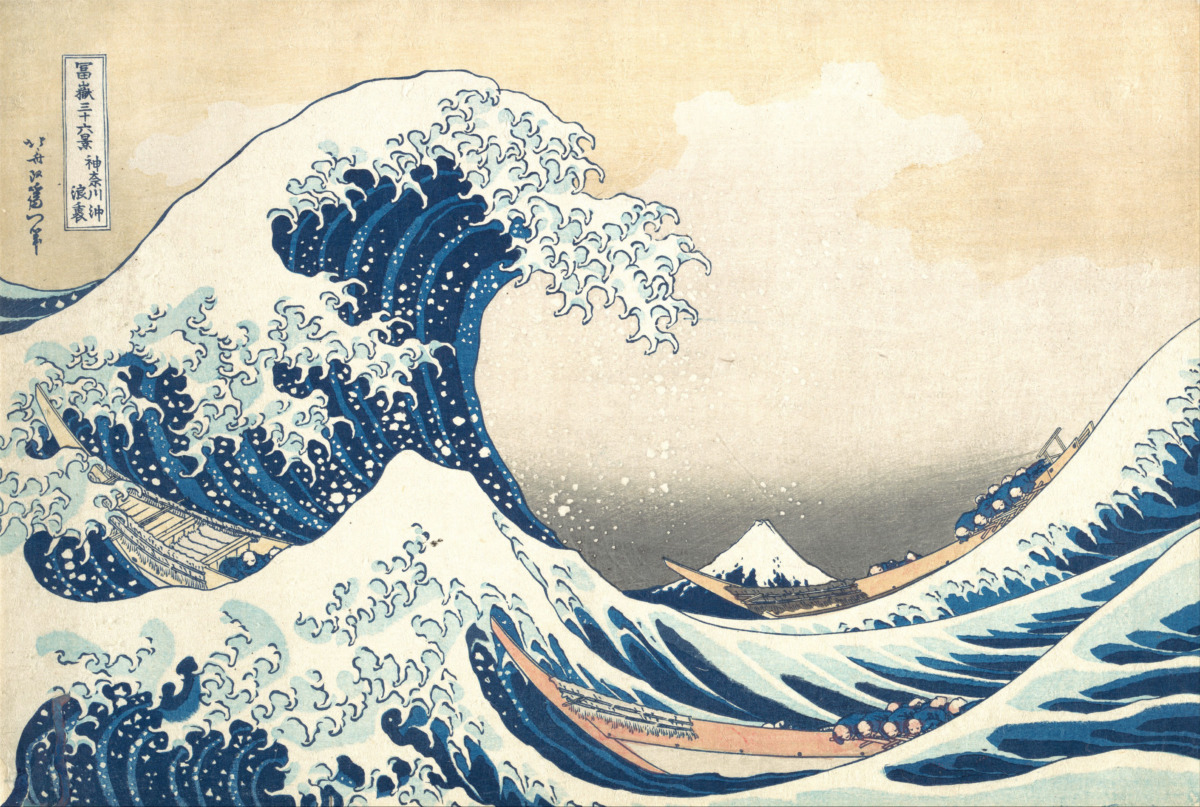

In case you think the history of Prussian Blue is a bit too appalling, allow me a chance to redeem it. A good many beautiful works of art were created with Prussian Blue, including Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa (1832) and Van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889). There is also a potentially interesting connection between the two. Prussian Blue did not became popular amongst the Europeans until sometime in the mid-to-late 1800s: after the color was imported to Japan in 1829, works created with Prussian Blue quickly became in high demand. When Japanese prints made with Prussian Blue found their way back to Europe, they named the exotic color “Hiroshige Blue,” after the Japanese printmaker who used the color extensively. It seems the people in the West were unaware that the origins of the pigment was actually in Germany. And so, Van Gogh, who collected Japanese prints and who was inspired by their beauty, color, and other formal qualities, may have begun using Prussian Blue as a result.